Dear Gentle Readers: I welcome today Janine Barchas with her review of the recently published Jane Austen: A New Revelation by Nicholas Ennos – his book tackles the question of who really authored Jane Austen’ s six novels and juvenilia…

***************

“Conspiracy is the Sincerest Form of Flattery”

Review of Nicholas Ennos, Jane Austen: A New Revelation (Senesino Books, Oct. 2013). Pp. 372. £25. Available from Amazon.com as an e-book for Kindle for $10.99.

The litmus test of true literary achievement is whether your works are deemed so great that you simply could not have written them.

Janeites need no longer envy students of Shakespeare their intricate web of Renaissance conspiracy theories. Whereas Shakespeare scholarship has long enjoyed the spectral presence of the Earl of Oxford, Austen studies can now boast a countess named Eliza de Feuillide.

The self-published Jane Austen: A New Revelation alleges that “a poor, uneducated woman with no experience of sex or marriage” could not possibly have written the sophisticated works of social satire and enduring romance that we traditionally attribute to Jane Austen. The book’s author, Nicholas Ennos (the aura of conspiracy allows that this is not necessarily his/her real name), asserts that biographers have been leading everyone by the nose. The true author of the Austen canon is, instead, Madame la Comtesse de Feuillide, born Eliza Hancock (1761-1813). Eliza was the worldly and well-educated older cousin of Jane Austen who, after being made a young widow by the French Revolution, married Henry Austen, Jane’s favorite brother. The sassy Eliza has long been pointed to as a model for the morally challenged characters of Lady Susan and Mary Crawford in the fictions. To identify Eliza as the actual author was, Ennos explains, the next logical step.

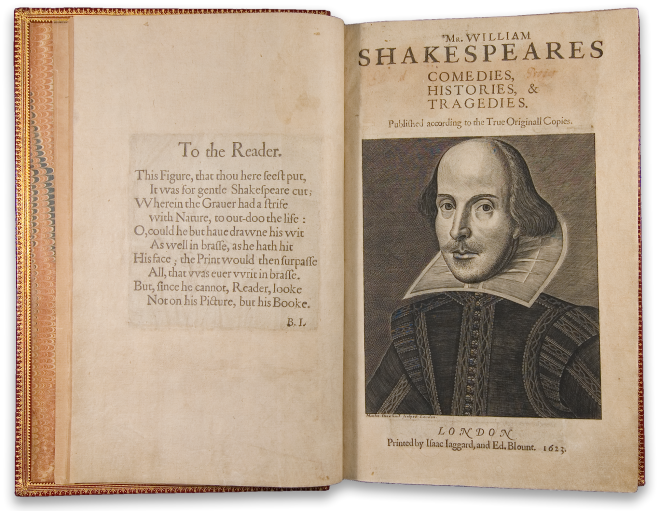

Shakespeare’s First Folio – Haverford.edu

Just so, and also about two centuries into his literary afterlife, William Shakespeare’s lofty literary achievements were judged incompatible with his humble origins, sowing seeds of doubt that a person so little known could have achieved so much. Slowly, the man named Will Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon came to be considered by a small-but-articulate fringe to be a mere front shielding the genuine author (or authors) of the works written under the pen name of Shakespeare. Austen’s genteel poverty, relative isolation, and biographical quiet allows for a similar approach. For how, asks Ennos, can genius thrive with so little food of experience to feed it?

The arguments for Shakespeare reattribution rely heavily upon biographical allusions as well as the absence of works in manuscript. Similarly, Austen critics who have been keen to spot biographical references to real places and family members in the fictions have apparently opened the door to skeptics who can now point to Cassandra’s “systematic destruction” of her sister’s letters as proof of a conspiracy. Ennos also draws attention to the “suspicious” parallel fact that no Austen novel survives in manuscript. The juvenilia, which does survive in Jane’s hand, is explained away as early secretarial work for Eliza during her visits to the Steventon household.

Eliza died in April of 1813, well before the publication of Mansfield Park (1814), Emma (1815), or Persuasion and Northanger Abbey (Dec 1817). The so-called Oxfordians overcame the timeline obstacles posed by Edward de Vere’s early death in 1604 by redating many Shakespeare texts, which (their logic dictates) must have been composed earlier than previously thought and squirreled away for later publication by an appointed agent. So too is the Austen corpus deftly redated by Ennos—with husband Henry, cousin Cassandra, and amanuensis Jane as co-conspirators. Some historians allow that Eliza was in all probability the natural daughter of politician Warren Hastings. Ennos adds to this existing context of secrecy that Eliza’s illegitimacy was the “disgrace” that the Austens “were determined to cover up after Eliza’s death” and the reason that “the myth of Jane Austen’s authorship was invented.”

Readers of Austen will doubtless need some time to process the implications of these revelations. For example, what of the presumed poignancy of Persuasion’s temporal setting? The events in this novel take place during the false peace of the summer of 1814—a short reprieve in the Napoleonic wars that saw the premature return of Britain’s navy men after the initial exile of Napoleon to Elba. Persuasion has been on record as composed between August 1815 and August 1816, in the full knowledge of both the false hopes of that summer and the true end to the war that came with the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815. Ennos moves the novel’s date of composition prior to April 1813. Although he does not go so far as to urge Eliza’s historical prescience, he suggests that these features are merely evidence of judicious tweaks to manuscripts left in Henry’s care at Eliza’s death.

Eliza de Feuillide Frances Burney Jane Austen

This is not all. Ennos further declares that the precocious Eliza also wrote the novels conventionally attributed to Frances Burney (1752-1840). The resemblances between Evelina and Pride and Prejudice have long been acknowledged by scholars who have (mistakenly, according to Ennos) attributed this to Burney’s literary influence upon the young Austen. Ennos reasons that Frances Burney’s lack of literary success after Eliza’s death, including her “truly dreadful” novel The Wanderer in 1814, is evidence of her being, in fact, an imposter. While future stylometric analysis may eventually confirm that Jane and Fanny were one and the same Eliza, this method has not settled the authorship question irrevocably for Shakespeare. Perhaps this is why Ennos does not turn to computer analysis or linguistics for help. He does identify Elizabeth Hamilton, the name of another minor authoress, as a further pseudonym used by the talented Eliza—ever widening the corpus of works that might appeal to those already interested in Austen.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the novels attributed to Jane Austen were published anonymously during her lifetime. Logically, any book written anonymously must be in want of a conspiracy. The grassy knoll of this particular conspiracy is the biographical notice in Northanger Abbey, released simultaneously with Persuasion six months after Jane Austen’s death in 1817. History has taken Henry Austen, a failed banker, at his word in identifying the author as his sister. Ennos, who is not very gallant towards the species of academics and literary critics whom he dismisses as “simple souls,” suggests that Austen scholarship has been surprisingly gullible in accepting Henry’s attribution without question.

In the wake of the Ireland forgeries of the 1790s, generations of Shakespeare scholars offered dozens of different names for the man behind the mask of “Will Shakespeare.” Although the Earl of Oxford has garnered Hollywood’s vote, Francis Bacon and Christopher Marlowe are next in popularity. We can only hope that these allegations by Ennos prop open the doors of Austen authorship so that additional candidates can step forward to provide generations of graduate students with dissertation fodder.

Does the Eliza attribution theory expect to be taken seriously? Or does this maverick publication deliberately mock established scholarship by means of cartoonish imitation? I’m not sure it really matters. If this project had ambitions to be a serious Sokal-style hoax, then it did not manage to convince a top publisher and, as a result, lacks the ability to wound deeply. The prose is also too earnest and unadorned for an academic satire—devoid of the jargon that should dutifully accompany a spoof. The resulting pace is too sluggish for irony. That said, there are plenty of moments that even David Lodge could not improve upon. For example, Ennos points to an acrostic “proof” of hidden clues in the dedicatory poem to Evelina (only visible if decoded into Latin abbreviations). There is also the syllogistic central assertion that if the novels of both Burney and Austen resemble the Latinate style of Tacitus, then these could only have been written by 1) the same person and 2) someone schooled in Latin. Ergo, Eliza is the true author behind both, since only she could have learned Latin from Reverend George Austen, Jane’s father (who might teach a niece but never his youngest daughter). Finally, there are gestures towards wider bodies of knowledge: “In this respect the philosophy of both authors has been linked to the views of the Swedish philosopher, Swedenborg.” Perhaps Ennos is simply angling for someone to buy the movie option. “Anonymous” did well at the box office, so why not a film dubbed “Eliza”?

No matter what the intention, hearty congratulations are due to Jane Austen. For her, this news makes for a strong start to the New Year. Exactly two centuries into her literary afterlife, a doubting Thomas was the last requirement of literary celebrity still missing from her resume. Austen can now take her seat next to Shakespeare, secure in the knowledge that her authorship, too, has begun to be questioned.

You know you’ve hit the big time when you didn’t write your own work.

— Reviewed by Janine Barchas

*****************

Barchas is the author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity (Johns Hopkins, 2012). She is also the creator of “What Jane Saw”, an on-line reconstruction of an art exhibit attended by Jane Austen on 24 May 1813. Recently, she has written for The New York Times and the Johns Hopkins University Press Blog.

Very interesting. There is a counter argument of course that a formal education is a hindrance to creative thinking and a barrier to becoming a great writer.

Lets think of some writers with poor or minimal education. D H Lawrence, Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, for straters and some more modern writers; Dylan Thomas came from only a lower middle class background in Swansea with an average education, Doris Lessing, probably one of the greatest wrieters of the 29th century, who has died recently, was just a little old lady who kept out of the limelight as much as possible and went shopping incognito to her local supermarket. I am sure there are many many others from inauspicious backgorunds. .

What they did have in common was a genius for observation and exploring the human condition and being able to write about that in amazing ways. You can’t be taught that and these people were not.

Final thought,, Wordsworth!!!!Ha!! It was really Dorothy you know.

I will end there.

Tony

LikeLike

Yes, Tony, a very good listing of the various names of your best writers – there are a good number of them from here too! [and of course it was Dorothy all along!]

LikeLike

I knew it! William was a foil for the genius Dorothy!

LikeLike

I did mean the 20th century. My keyboard plays tricks on me sometimes. ha! ha!

LikeLike

“There is also the syllogistic central assertion that if the novels of both Burney and Austen resemble the Latinate style of Tacitus, then these could only have been written by 1) the same person and 2) someone schooled in Latin. ”

Well I don’t know about that, I do not know much Greek or Latin. I do know that Greek and Latin pervades the way I think and write in todays society.. It is imbued in our language and society.

When I write something I use logic and chronology, I write in structures that are acceptable to the world I live in. I have not studied the philosophies involved. I am sure Jane Austen structured her writing and used words and phrases acceptable to her time. Of course she created her own creations out of all this but she was still connected with the society she lived in and wrote in structures that people understood..

It occurs to me that somebody such as this gentleman, Nicholas Ennos ( sounds like a character out of the Magus) can very easily set up an argument which then is difficult to refute. The reasons he has done this are open to debate.

Ha! I’ve just looked back at what I have written. The number of words i have used derived from Greek and Latin !!! I wasn’t even thinking about it. I must be a genius!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well it’s an interesting theory but I’m not sure I’ll be purchasing the book. I think the one person us Austen fans would love to know more about is the elusive Cassandra ….

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree Nicola, but alas! I think she will remain forever illusive unless we could miraculously stumble upon a treasure trove of HER letters – but I imagine she delegated most of those to the same place she sent most of Jane’s…

Thanks for stopping by Nicola,

Deb

LikeLike

HA! “The litmus test of true literary achievement is whether your works are deemed so great that you simply could not have written them.” Janine Barchas is bloody brilliant. I hope this quote becomes a truth universally acknowledged and is placed at the beginning of ever article ever written about literary conspiracies!

Oh joy, oh rapture unforeseen. Personally, I have always believed that Austen’s death in 1817 was faked. She was really turned into a vampire by Lord Byron and later wrote all the lyrics to the Savoy operas. Just say’n.

Many thanks to you and Janine for keeping us up to speed on Austen conspiracies Deb. I can’t remember when I have had a more enjoyable afternoon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always happy to oblige Laurel Ann! – very glad this essay brought such mirth into your day! – now the idea of Austen writing lyrics to the Savoy operas seems like a good idea for a book [I think Austen vampired by Byron has been taken] – sounds like a working plan for 2014, just in case you were in need of a project…?

LikeLike

Am I the only person ever who liked The Wanderer?

LikeLike

Pingback: Around the Web | AustenBlog

Now Mags,.

do you, by The Wanderer, mean a supporter of Bolton Wanderers Football Club? Their supporters are called The Wanderers. Do you mean the song ,”The Wanderer,” written by Ernie Maresca and originally recorded by Dion?

Or perhaps the 10th century poem called, The Wanderer, recorded in the illuminated manuscript called The Exeter Book? Or, even,, perhaps,, the novel The Wanderer, a 1949 novel by Mika Waltari?

Just wandering, I mean wondering.

Tony

LikeLike

Tony, you crack me up… Mags was talking about Dion obviously…I think Eliza de Feuillide wrote that song.. [or was it that VERY long, VERY wandering book written by Frances Burney [or is that Eliza deF too?] – all very confusing…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating stuff! I suppose Eliza also wrote Jane’s letters? Those are far too sharp and witty to have been penned by a country bumpkin.

LikeLike

Hello Catherine! – yes, what about the letters indeed! – I haven’t finished the book yet – will let you know how he figures that piece out….know that he thinks Eliza wrote all the Juvenilia…

Thanks for stopping by – always nice to hear from you!

LikeLike

Thank you thank you for this article. I was trying to figure out if this book was a joke or not and couldn’t find any information aside from the book blurb.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant review: exactly the right tone, no mocking just hard questioning. And let’s face it, it’s true: you know someone’s significant when the fringe scholars (usually intelligent, well-educated people) find it so hard to believe that that Someone could possibly have done so much to outshine them, while lacking their advantages… This could be the start of something so much more rewarding than all the ‘Austen Vampires’, Austen murder mysteries, etc… ! :-)

LikeLike

Shakespeare wrote Austen’s books because she was too busy writing his plays. Seems obvious to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this! Thanks for the chuckle!

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. How funny to find a reply to this. I’d quite forgotten it. I came across an article which mentioned this book about how Jane Austen did not write Jane Austen in my old school’s magazine. The author is a former pupil. I doubt if they are particularly proud of him.

I have become increasingly angry about this sort of nonsense. What might once have seemed harmless, even amusing speculation about Who Wrote Shakespeare etc now seems more like a subset of that whole industry of web-based lying and distortion which infects far wider areas than literature.

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

I’ve not read the book, but I find Ennos’s idea that Jane Austen couldn’t have written something she’d never lived quite ridiculous.

I very much enjoyed this review. Though, I find the author’s way of promoting their book unnerving. They seem to be leaving comments on Jane Austen related youtube videos claiming their book as ‘proof’ rather than as a conspiracy theory. And they’re recent, from 2018, not 2014, when it was originally published.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, C.J., I also found this sort of promotion (on the part of the… ahem…author) more than a tad trite. I felt it a bit of a yawn, really, and hoped the host of said YouTube vid would, in the characteristically responsible way of Oxford, simply delete it. Alas, we true Janeites (True Jane, that is) bear the perennial burden of Being Able To See Through The Smokescreen of Vanity & Pomp. So, there it is, I suppose.

LikeLiked by 1 person

While I have no inclination to believe in a conspiracy theory from a moon-landing denier, I also don’t think you refuted his claims very well. Simply saying he must be wrong because he’s doing what people have tried to do to Shakespeare isn’t convincing.

LikeLike

Did Eliza de F. also write Fanny Burney’s diaries ?

LikeLike