Gentle Readers: Today I welcome Tony Grant as he writes about his visit this week to the “EMMA 200” exhibit at Chawton House Library, he being my feet on the ground so to speak as I am woefully not able to be there myself. Hope those of you who are able to go will do so – and send me pictures and your thoughts when you do!

[Update: please read Tony Grant’s post about walking around Chawton at the “Jane Austen’s World” Blog]

EMMA 200: English Village to Global Appeal

(Chawton House Library 21st March – 25th September 2016)

On Wednesday 20th April I drove from Wimbledon to Chawton in Hampshire over the Hogs Back with views stretching across Surrey into the distance. It was a bright sunny day and seeing the Surrey countryside green and pleasant and shining in the bright sunshine under blue skies was appropriate for my adventure. I was driving to Chawton House Library to visit the “Emma 200 exhibition.” Emma is Jane Austen’s Surrey novel and this year is the 200th anniversary of its publication and it is entirely set within that county.

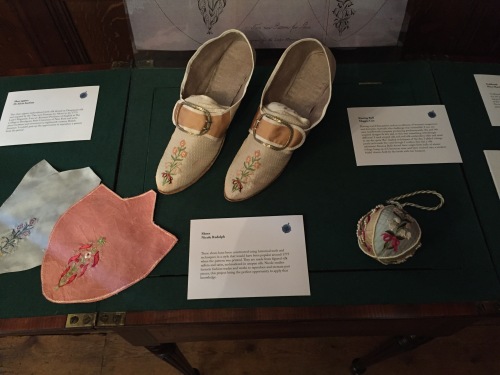

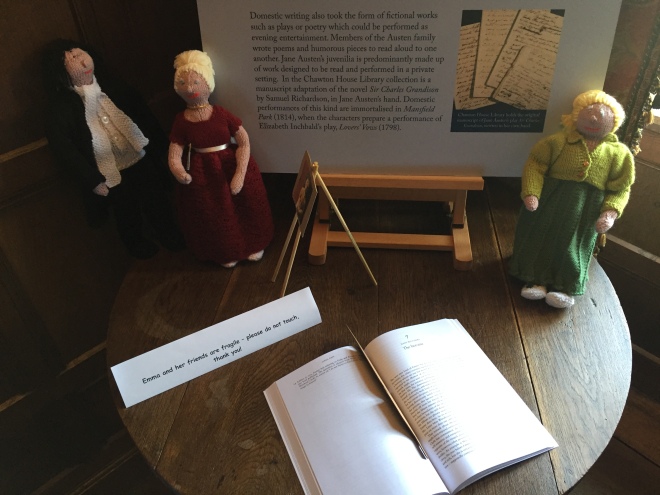

Emma was published by John Murray II of Albemarle Street on the 23rd December 1815, although its title page reads 1816. This exhibition has items from Chawton House’s own collection and from the Knight family collection, as well as other items on loan. The exhibition covers the reception of Emma through the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty first centuries; it also considers the country setting of the novel and the places that were possible influences. It covers the global appeal of Emma. It has a large section about John Murray II and nineteenth century publishing practices through letters and comments made by Jane herself and fellow authoresses also published by Murray. It highlights authors mentioned in the novel and nineteenth century ideas about female accomplishments such as music, embroidery and painting. It shows the connection with Shakespeare and has a section about the reception of the novel. In particular, there is a letter written by Charlotte Bronte to her own publisher, W.S. Williams, discussing her thoughts about Emma and Jane Austen as a writer.

Emma was published by John Murray II of Albemarle Street on the 23rd December 1815, although its title page reads 1816. This exhibition has items from Chawton House’s own collection and from the Knight family collection, as well as other items on loan. The exhibition covers the reception of Emma through the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty first centuries; it also considers the country setting of the novel and the places that were possible influences. It covers the global appeal of Emma. It has a large section about John Murray II and nineteenth century publishing practices through letters and comments made by Jane herself and fellow authoresses also published by Murray. It highlights authors mentioned in the novel and nineteenth century ideas about female accomplishments such as music, embroidery and painting. It shows the connection with Shakespeare and has a section about the reception of the novel. In particular, there is a letter written by Charlotte Bronte to her own publisher, W.S. Williams, discussing her thoughts about Emma and Jane Austen as a writer.

I arrived at the electronically operated gates early. The house opens at 1.30pm Monday to Friday. I was there promptly at 1.10pm. I decided to have a look around and inside of St Nicholas Church nearby, which is Chawton’s parish church and where Jane Austen and her family worshipped. The church we see today is not the church Jane knew. There was a fire sometime after Jane’s death and it had to be rebuilt, though some of the structure from the church that Jane knew remains. I read the memorials to the Austens and Knights within and then went round to the back of the church through an arbor of dark and gloomy ancient yew trees to see the side-by-side graves of Austen’s sister, Cassandra Elizabeth Austen, and mother, Cassandra Austen.

**************

It was such a nice day and I still had about ten minutes left so I sat on a stone bollard near the entrance gate and watched a gentleman sitting on a motor mower mowing the grass verges along the drive. As I sat there I noticed a smartly dressed lady leaving the front entrance of the great house with a dog on a lead. She approached the gate and opened it, placing a notice board on a stand giving the times and prices of entry. I asked jokingly if this meant I can go in. I pointed out it was still ten minutes to half past. She laughed and said by the time I walked up the driveway I should arrive at the door on time. “Just knock and they will let you in,” she told me. I knocked on the door with five minutes to and it was immediately opened by a smiling lady who ushered me in. The house is staffed by volunteers except in the kitchens where the official housekeeper keeps her domain but more about that nice lady later. I found everybody so enthusiastic and full of smiles and really, extremely welcoming. I paid my entrance fee and one lady took me into the great hall on the left of the entrance and showed me a map of the house with the route marked by numbered rooms. It is a self-guided tour so I was given the map to hold as I went round. There are volunteers in every room who you can talk to and ask information of.

**************

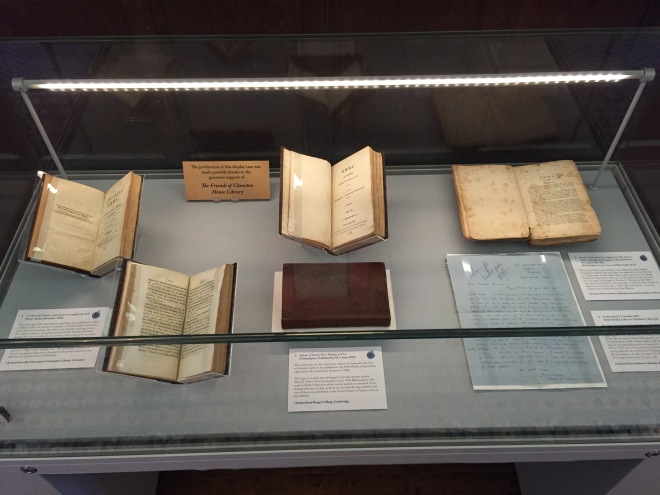

The exhibition began in the great hall. A glass case displays some first editions dated 1816. There was an edition in French as well as one published by Mathew Carey a publisher in Philadelphia. Somehow Carey had read Sir Walter Scott’s review of Emma and obviously liked it. He sold his version at a much cheaper price than John Murray’s London version. He produced a card backed version printed on cheap paper for $2. Murray’s London version, which was a much better quality, was twice the price. Very few American first editions have survived as a consequence of the poorer quality and the copy in this exhibition shows signs of much yellowing of the paper and black mold spots. It looks an inferior book to both the French and English versions. I felt honoured to able to lean over the glass case and read the opening few lines of the Murray edition.

“Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence:…”

There were no such things as copyright laws in those days and both the French and American versions, probably unknown to Jane Austen, brought her no income. Later in the nineteenth century Dickens went over to America and tried to do something about copyright laws in America but to no avail and to his great consternation. The fact that copies of Emma were being published abroad within the first year of its initial publication in England tells us something about publishing and the book trade at the time. Money could be made from books.

*****************

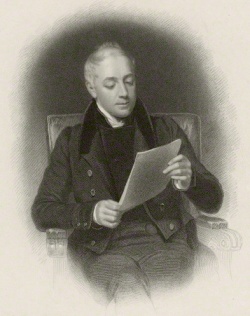

John Murray II was the head of the foremost publishing company in Britain. He was a hard headed business man and if he could get an advantage, especially, it seems over the authors he published he would. I think Jane Austen had the measure of him. Her brother Henry who had dealt with publishers for Jane initially became ill and Jane took over negotiations with Murray herself. She was very direct and firm in her dealings. She said of Murray, “He is a Rogue, but a civil one.” In corresponding with Murray over the publication of Emma, for instance, on 3rd of November 1815, a month before the publication of Emma, she writes,

“…I am at the same time desirous of coming to some decision on the affair in question, I must request the favour of you to call on me here, on any day after the present that may suit you best, at any hour in the evening, or any in the morning except from eleven to one. – A short conversation may perhaps do more than much writing.”

It sounds as though Murray has been given his marching orders and she isn’t going to have any truck with being messed about. She is firm but polite with the “Rogue.” She knows the power of a face to face encounter. Some of her contemporaries were perhaps not quite so strong with Murray but learned a lesson.

One of the exhibits on display, putting Jane Austen’s publishing experiences with Murray in context, is a book called Domestic Cookery, published by Murray in 1806. It was very popular and made a lot of sales and presumably a lot of money for Murray. It was written by Maria Rundell. Rundell had been paid £150 by Murray. She regarded Murray as a friend but she was not aware at first that her book had become such a bestseller. When she found out she felt that Murray was not upholding the copyright agreement he had with her. Eventually Murray paid her £2100 but kept the right to continue publishing the book himself. Jane Austen’s comments about him being “a rogue but a civil one” come to mind. Murray was obviously a very astute business man and could make money from trouble.

Another exhibit displays copies of books written by the French authoress, Germaine de Stael. She wrote books about Rousseau, Revolutionary Politics and Marie Antoinette’s trial. She was virtually banned by Napoleon Bonaparte. He had her book, De L’Allemagne pulped. Murray saw a chance. He took her on. In 1813 he used three printers to publish the French original and English translations simultaneously. He relied on anti-French feelings to make Stael’s books best sellers.

Jane Austen had her critics who made both good and not so good comments about her work. She took notice of what people said about her books and noted down these various opinions. Sir Walter Scott, her illustrious contemporary, who was also published by John Murray, wrote of Emma,

“We bestow no mean compliment on the author of Emma, when we say that keeping close to common incidents, and to such characters that occupy the ordinary walks of life, she has produced sketches of such spirit and originality that we never miss the excitation which depends upon a narrative of uncommon events, arising from the consideration of minds, manners and sentiments greatly above our own.”

It appears that Murray regularly sent copies of newly published books to other writers he published for their comments. This can be seen as eliciting positive comments from people who wanted to keep in with Murray. Jane Austen mentions in her letters to Murray how thankful she is for the copy of Waterloo he sent her to read and actually asks him if he has any more she can have a look at. This suggests she knows how to play the publishing game. She is as astute as Murray himself it seems. In one way Scott’s positive comments could be read as keeping in with Murray. If Murray and his publishing house does well and sells lots of books it can only benefit himself after all, but there is more to Scott’s review. I think he has recognized what is original in her writing. She is a realist. Her style is about everyday common occurrences and everyday people and she makes them heroic. People reading Jane Austen can see themselves and people they know in her writing. It is said that reading a novel is good emotional and psychological therapy, and Austen hit a powerful vein.

The highlight of the whole exhibition for me, even more so than seeing and reading a first edition, is the actual letter Charlotte Bronte wrote to her publisher, W.S. Williams, on April 12, 1850, in which she writes a lengthy paragraph about her thoughts on Jane Austen and Emma. I found it easy to read Bronte’s small, thin, precise handwriting that flows clearly across the page.

“I have likewise read one of Miss Austen’s works—Emma—read it with interest and with just the degree of admiration which Miss Austen herself would have thought sensible and suitable. Anything like warmth or enthusiasm—anything energetic, poignant, heart-felt is utterly out of place in commending these works: all such demonstration the authoress would have met with a well-bred sneer, would have calmly scorned as outré and extravagant. She does her business of delineating the surface of the lives of genteel English people curiously well. There is a Chinese fidelity, a miniature delicacy in the painting. She ruffles her reader by nothing vehement, disturbs him by nothing profound. The passions are perfectly unknown to her; she rejects even a speaking acquaintance with that stormy sisterhood…”

Bronte continues:

“What sees keenly, speaks aptly, moves flexibly, it suits her to study; but what throbs fast and full, though hidden, what the blood rushes through, what is the unseen seat of life and the sentient target of death—this Miss Austen ignores. “

And she goes on. Charlotte Bronte is actually agreeing with Scott’s comments when he describes her writing as

“……close to common incidents, and to such characters that occupy the ordinary walks of life”

The difference is that Scott makes his view a positive while Bronte makes her view a negative. I agree with what she says. Austen writes about the ordinary. Bronte on the other hand and her sisters wrote about,

“what throbs fast and full, though hidden, what the blood rushes through, what is the unseen seat of life and the sentient target of death”

Charlotte Bronte is actually describing the differences between their two styles. I have read articles published on some blogs where the writer tries to pit Charlotte Bronte against Jane Austen. Who do you like the best? Who do you think is the better writer? And so on. These are a childish approach to comparing two great writers. Two geniuses. Their styles are different. Every one of us reads different types of books for different reasons at different times to fit, very often , our different moods. We can read a poem by Wordsworth one day and on other days a romantic comedy, a ghost story, a swashbuckling adventure, a horror story or maybe a present day thriller. We can enjoy each genre for what it is and what it brings to us. Austen and Bronte are not enemies, they are not one better than the other. They are different and we can enjoy both. I can imagine how Bronte could be critical. She had a harder life than Jane Austen. Her novels and those of her sisters, were full of passion and deep feelings and filled with great moral uncertainties testing the moral status quo to the limit. Their ideas made their lives worth living and helped them live their short lives with feeling. Jane Austen had a much easier existence. I can see how Charlotte Bronte might not understand Austen’s standpoint. She probably could not bear to live the way Austen’s characters are portrayed. However, we can love them both.

The exhibition demonstrates many of the influences Jane Austen might have used in her writing of Emma. There is the suggestion, for instance, that the fictional places Highbury and Hartfield in Emma are modelled on Chawton and the local town Alton. These are in Hampshire but the novel is set in Surrey. Others I know would not agree. Some say Leatherhead in Surrey, which is near Box Hill, a major location in the book. Others suggest Highbury is a generic English village, and I think this more likely.

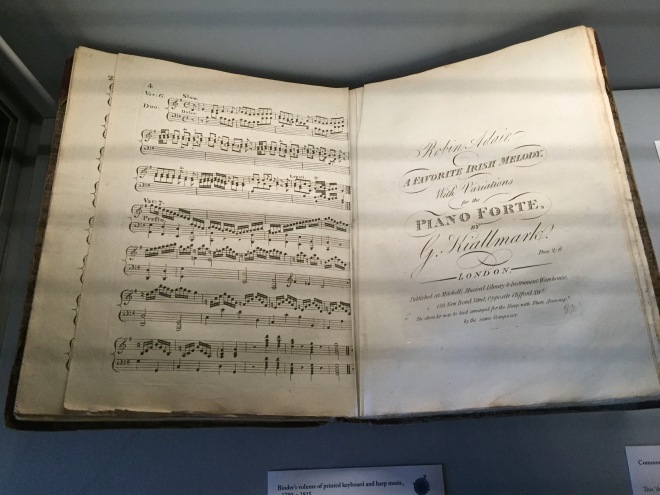

In Emma Jane Fairfax plays a tune called “Robin Adair” on the newly arrived pianoforte. There is on display a copy of “Binder’s volume of printed keyboard and harp music, 1780-1815,” annotated and autographed by Jane’s sister Cassandra. It includes the music to “Robin Adair.” [Ed. You can read this online here: https://archive.org/details/austen1677439-2001 ]

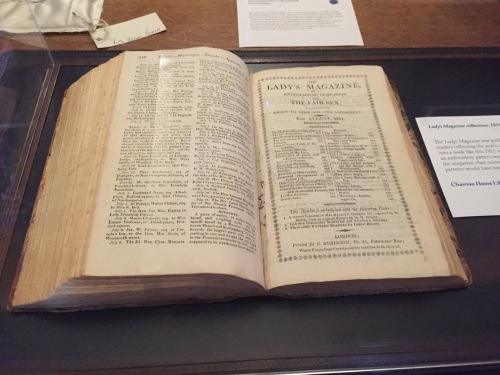

There is a bound set of The Ladies Magazine (1770-1832) which provides sewing patterns for young ladies. It is the sort of magazine that Jane Austen had access too. In Emma, sewing and painting are pastimes for young ladies.

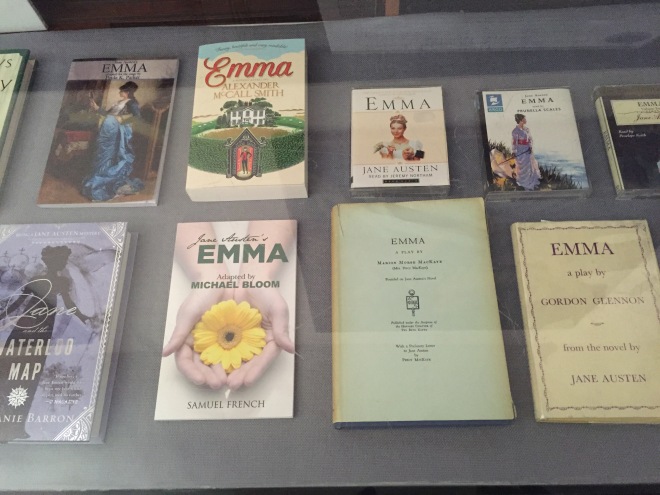

A final display cabinet shows the influences that Emma has had on culture over the centuries. There are various spin-off novels, including the latest modern version of Emma written by Alexander McCall Smith. There are play scripts written by various playwrights turning Emma into a stage version. These include plays by Gordon Glennan and Marion MacKaye. There are a number of radio adaptations. One read by Prunella Scales, another by Jeremy Northam. There are the film versions and the films influenced by Emma such as Clueless set in modern times. Spin-off novels are represented by a copy of the latest Stephanie Barron mystery The Waterloo Map. [Ed. Note that this latest Barron mystery has Jane visiting Carlton House where she meets with the Prince Regent’s Librarian – this all really took place on 13 November 1815; he “suggests” that she dedicate her newest book, Emma, to the Prince Regent – Barron has her also coming upon a dead body in the Library…]

****************

The exhibition is definitely worth seeing and just as much is the opportunity to walk around Chawton House where Jane Austen herself and her family lived and breathed. I also took the opportunity to take a walk in the gardens. I came across a snake lying across my path as I walked up to the walled gardens. I must tell you that in all my life I only recall seeing two other snakes in Britain in the wild. This was a grass snake and was totally harmless. The adder is the only poisonous snake in Britain and they are very shy creatures. I think I saw one once in the New Forest.

*************

The people who volunteer at Chawton are wonderful. They want to talk to you and tell you things. I had a very amusing moment with an elderly gentleman volunteer at the top of the great staircase. He was sitting on the landing. When I approached he showed me an information leaflet and we discussed its contents. One thing it mentioned was the original William Morris wallpaper. I looked around and couldn’t see any. “Well, then where’s the wallpaper?” I joked. He laughed and said “come with me.” We walked half way down the staircase and then turned and got on our hands and knees. There indeed, almost hidden behind the balustrade, was a patch of darkened William Morris print. He also kindly showed me the large 1714 map of London displayed on the folding panels of a screen.

We found Henrietta Street and other places associated with Jane Austen when she visited London. Then I went into the old kitchen which is used as a shop and cafe and met a lovely lady who told me she was the housekeeper. I had a delicious chocolate cake and a cup of coffee. All together I had a wonderful visit to the “Emma 200 exhibition.”

Further reading:

- Chawton House Library: http://www.chawtonhouse.org/

- Emma at 200 Exhibition: http://www.chawtonhouse.org/?p=60916

- CHL podcast on the exhibition: http://www.chawtonhouse.org/?p=61374

- Review at the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies website: https://www.bsecs.org.uk/criticks-reviews/emma-at-200-from-english-village-to-global-appeal/

- Review at the Austenised blog: http://austenised.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/the-highlights-of-emma-200-from-english.html

- Emma‘s Publishing History at JAIV: https://janeausteninvermont.wordpress.com/2015/12/16/the-publishing-history-of-jane-austens-emma/

- “Emma in the Snow at Sarah Emsley”: https://sarahemsley.com/emma-in-the-snow/

[All photographs c2016 Tony Grant unless otherwise indicated]

What a lovely review Tony! I’m the curator of the exhibition, and executive director of Chawton House Library, and I hope everyone who comes gets as much out of it as you did. I’ll pass on your comments to the team – and especially our volunteers. We couldn’t manage without them

LikeLike

Thank you Gillian for stopping by – always happy to encourage people to visit and donate to Chawton House Library and to add to the press on this exhibit. So grateful Tony could be my proxy there – he has a good eye and sees much that others might miss – even snakes in the grass!

And yes, please thank your volunteers for all that they do…

LikeLike

Gillian it is the first time I have been inside the house. Your volunteers were so enthusiastic and helpful. I enjoyed their company. The exhibition , its theme and scope is excellent. All the best, Tony

LikeLike

Wonderful – so pleased you enjoyed it. Our volunteers will be delighted – they work really hard on our behalf.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tony and Deb, I enjoyed this very much! I would so love to have been there myself but, as always, Tony has made me feel as if I had been. I agree, there’s no need to choose between Brontes and Austen; I love them all. Now I’m off to tweet a link to this post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jean as always for stopping by and commenting – and I agree about the Brontes and Austen – we need to embrace them all! it’s not an either / or proposition for me – my favorite book has always been and reinforced with numerous re-reads, and despite my love for Jane Austen, Jane Eyre…

LikeLike

Jean, thank you for your comment. It was wonderful to see those first editions. I also got a real thrill out of being able to see and read the actual letter Charlotte Bronte wrote to her publisher mentioning Emma.

LikeLike

Just lovely. Thanks, Tony and Deb, for this virtual visit. :)

LikeLike

One day Vic!!!!!

LikeLike

Thanks for stopping by Vic!

LikeLike

Enjoyed reading your review, Tony! Lovely photos and interesting to read more about Murray and the publishing practices at the time. I have to agree with you on the Austen/Bronte debate – no point in arguing who is better as they both had their own approaches and strengths based on their different experiences and influences. Did you see what was left of Edward Austen’s Regency Garden? I missed seeing the gardens as it started hailing when I came out of the house!

Thanks for linking to my blog as well, Deb.

LikeLike

Hi Anna. Thanks for responding. I walked up to the walled garden( kitchen garden) at the back of the house. It is a typical set up for a grand houses kitchen garden. I am not sure I saw the remains of the Regency garden! I walked on past the walled gardens to the end of the path that provides views out over the extensive landscape. I think I read somewhere that the estate grounds have been returned to how they were in the 18th century before the field system took over in the agricultural revolution, but I might be wrong. Need to look into that a bit more.

Well the only thing for you now to do is go again on a sunny day, Anna. As you say, you can get a nice pint of beer at the Greyfriars. I had a meal there once with some friends . They have a very good menu and the food is of a high standard.

LikeLike

Wonderful post and photos! Thank you, Tony and Deb.

LikeLike

Thanks for stopping by Sarah!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you as well for the link to “Emma in the Snow”!

LikeLike

Thank you Sarah.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: A Walk Through Chawton, Jane Austen’s Home | Jane Austen's World

In the very last photo, are those beautiful heraldic stained glass windows in Chawton House where Jane lived? I’m not clear if its a window from the Chawton House Library as a separate building. The stairwell with the portrait of a lady says CHL and another gorgeous stained glass window. Stunning..as is the stairwell..

LikeLike

Yes, Lady L – those are the windows in Chawton House Library in the stairwell – same as in the picture with the portrait on the staircase. I’ll have Tony tell you more about them – I do not know what they stand for – some detective work required!

Thanks for visiting.

LikeLike

Hi Lady L. They are heraldic emblems. I am not sure who they belong to or their meaning. I took the photograph of the stairwell with the portrait because I thought the lady in the picture looked rather nice. There is not much information on display explaining the portraits or the windows.

Both photographs are interior shots of Chawton House Library.

Jane lived in a cottage with her mother, sister Cassandra and friend Martha Lloyd about half a mile from Chawton House in Chawton Village. She visited the great house often because her brother ,Edward Knight, lived there. I am sorry I can’t be more help with the stained glass emblems. As soon as I find out more I will post about them. All the very best, Tony

LikeLike

Lady L and Tony – I will be posting something this week about the windows, so stay tuned – all very interesting!

LikeLike

Pingback: Emma at 200, John Murray, and Stitch-Off, The Movie | Chawton House Library