UPDATE: Prices realized noted in red as they become available

There are a number of Jane Austen materials coming up for auction in the next few weeks, some actually affordable! – and then some, not so much… here are brief synopses – visit the auction house websites for more information.

This one is a bit different and an interesting addition to anyone’s Pride and Prejudice collection!

November 18, 2012. Heritage Auctions, Lot 54353. Pride and Prejudice 1939 Movie photographs:

Pride and Prejudice (MGM, 1939). Photos (16) (8″ X 10″). Drama.

Vintage gelatin silver, single weight, glossy photos. Starring Greer Garson, Laurence Olivier, Mary Boland, Edna May Oliver, Maureen O’Sullivan, Ann Rutherford, Frieda Inescort, Edmund Gwenn, Karen Morley, Heather Angel, Marsha Hunt, Bruce Lester, Edward Ashley, Melville Cooper, Marten Lamont, E.E. Clive, May Beatty, Marjorie Wood, Gia Kent. Directed by Robert Z. Leonard.

There are 14 different photos with a duplicate each of 1136-190, and 1136-149; unrestored photos with bright color and a clean overall appearance. They may have general signs of use, such as slight edge wear, pinholes, surface creases and crinkles, and missing paper. All photos have a slight curl. Please see full-color, enlargeable image below for more details. Fine.

SOLD $179.25 (incl buyer’s premium)

**********************

November 18, 2012. Skinner, Inc. – Fine Books and Manuscripts, Boston. Sale 2621B

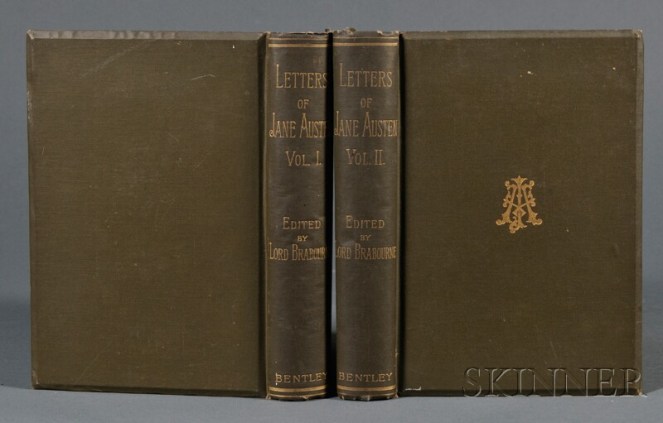

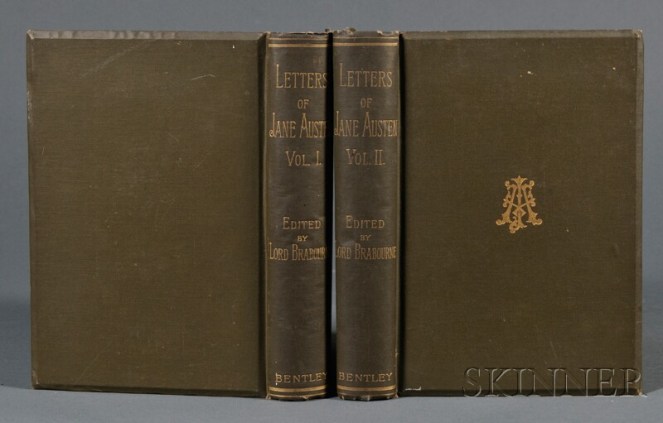

Lot 208: Austen, Jane (1775-1817). Letters. London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1884.

Octavo, in two volumes, first edition, edited by Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen, first Baron Brabourne (1829-1893), in publisher’s green cloth, ex libris Henry Cabot Lodge, with his bookplate; preliminaries in volume one a bit cockled, with some discoloration.

Jane Austen’s letters speak for themselves: “Dr. Gardiner was married yesterday to Mrs. Percy and her three daughters.” “I cannot help thinking that it is more natural to have flowers grow out of the head than fruit? What do you think on the subject?”

Estimate $300-500. SOLD $250. (incl buyer’s premium)

*****************

Lot 4 : AUSTEN, JANE. Northanger Abbey. Volume 1 (only, of 2). 12mo, original publisher’s drab boards backed in purple cloth (faded to brown), lacking paper spine label, edgewear; text block almost entirely loose from spine, few binding threads and signatures loose, several leaves in first third heavily creased, few other margins creased; else quite clean overall. Philadelphia: Carey & Lea, 1833

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION AND ONE OF 1250 COPIES. In need of some repair, but complete and in original cloth. All First American Editions of Austen are difficult to find. Later printings of this title did not occur until 1838, as a one-volume collected edition and, as a single volume in 1845. Gilson B5.

Estimate $500-750. SOLD: $600. [incl buyer’s premium]

**********************

This is the big one!

November 21, 2012. Christie’s. Valuable Manuscripts and Printed Books. London. Sale 5690.

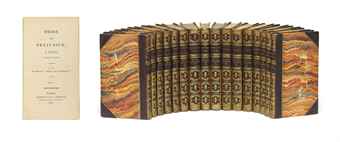

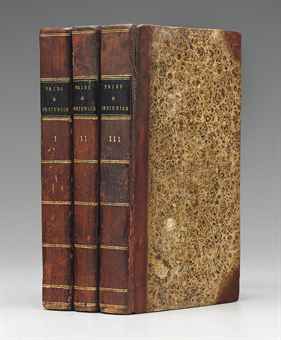

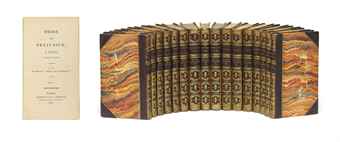

Lot 150: AUSTEN, Jane (1775-1817). Sense and Sensibility … second edition. London: for the author by C. Roworth and published by T. Egerton, 1813. 3 volumes. (Lacks half-titles and final blanks, some browning and staining.) Gilson A2; Keynes 2.

Lot Description

AUSTEN, Jane (1775-1817). Sense and Sensibility … second edition. London: for the author by C. Roworth and published by T. Egerton, 1813. 3 volumes. (Lacks half-titles and final blanks, some browning and staining.) Gilson A2; Keynes 2.

Pride and Prejudice. London: T. Egerton, 1813. 3 volumes. (Lacks half-titles, lightly browned, a few leaves slightly torn along inner margin or with fragments torn from outer margin, margin of B10 in vol. I a little soiled, title of vol. III with slight stain at bottom margin, quires I and M in same vol. somewhat stained.) FIRST EDITION. Gilson A3; Keynes 3.

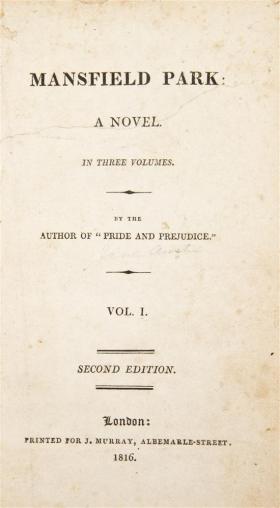

Mansfield Park. London: T. Egerton, 1814. 3 volumes. (Lacks half-titles, without blank O4 in vol. II or final advertisement leaf in vol. III, weak printing impression affecting 3 lines on Q10r.) FIRST EDITION. Gilson A6; Keynes 6.

Emma. London: John Murray, 1816. 3 volumes. (Lacks half-titles, E12 of vol. I misbound before E1, tear to bottom margin of E7 in vol. II, other marginal tears, L7-8 of vol. II remargined at bottom, title of vol. III with closed internal tear, some spotting, staining and light soiling.) FIRST EDITION. Gilson A8; Keynes 8.

Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. London: John Murray, 1818. 4 volumes. (Lacks half-titles and blanks P7-8 at end of vol. IV, some browning and spotting.) FIRST EDITION. Gilson A9; Keynes 9.

Together 6 works in 16 volumes, 12° (177 x 100mm). Uniformly bound in later 19th-century black half morocco over comb-marbled boards, marbled endpapers and edges (vol. I of Mansfield Park with scuffing at joints and upper corner of front cover).

Second edition of Sense and Sensibility, ALL OTHER TITLES IN FIRST EDITION. A rare opportunity to purchase the six most admired novels in the English language as a uniformly bound set. (16)

Estimate: £30,000 – £50,000 ($47,610 – $79,350) SOLD: £39,650 ( $63,004) (incl buyer’s premium)

**********************

November 27, 2012. Bonham’s. Printed Books and Maps. Oxford. 19851.

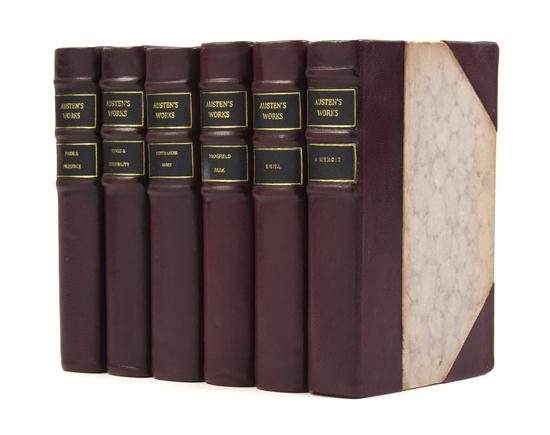

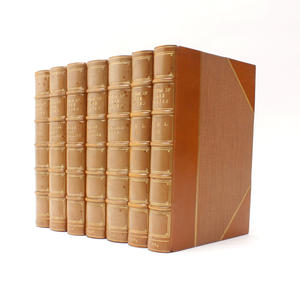

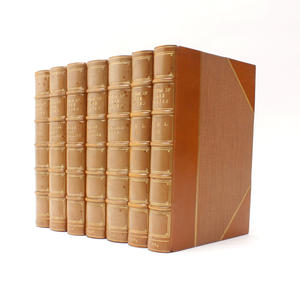

Lot 26: AUSTEN (JANE) The Novels…Based on Collation of the Early Editions by R.W. Chapman. 5 vol., second edition, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1926; together with The Letters of Jane Austen, 2 vol., frontispieces, uniform half calf by Hatchards, gilt panelled spines, faded, 8vo, Richard Bentley, 1884 (7)

Lot 26: AUSTEN (JANE) The Novels…Based on Collation of the Early Editions by R.W. Chapman. 5 vol., second edition, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1926; together with The Letters of Jane Austen, 2 vol., frontispieces, uniform half calf by Hatchards, gilt panelled spines, faded, 8vo, Richard Bentley, 1884 (7)

Estimate: £300 – 500 ( US$ 480 – 810); (€380 – 630) – SOLD: £525 ($844.) (incl. buyer’s premium)

**************************

December 7, 2012. Christies. Fine Printed Books and Manuscripts Including Americana. New York. Sale 2607.

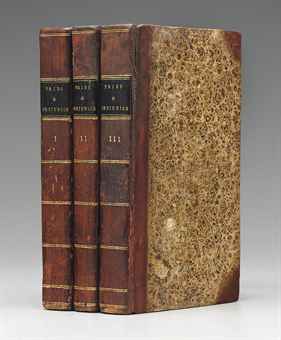

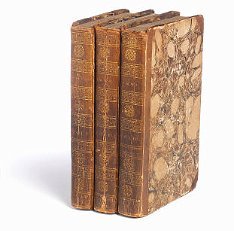

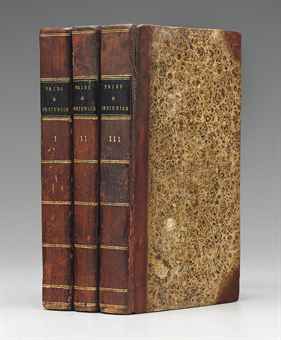

Lot 140: [AUSTEN, Jane (1775-1817)]. Pride and Prejudice. London: Printed for T. Egerton, 1813.

Lot Description:

[AUSTEN, Jane (1775-1817)]. Pride and Prejudice. London: Printed for T. Egerton, 1813.

Three volumes, 8o (171 x 101 mm). Contemporary half calf and marbled boards, spines gilt-ruled, black morocco lettering pieces (a few stains and some rubbing); cloth folding case. Provenance: H. Bradley Martin (bookplate; his sale Sotheby’s New York, 30 April 1990, lot 2571).

FIRST EDITION. Originally titled First Impressions, Pride and Prejudice was written between October 1796 and August 1797 when Jane Austen was not yet twenty-one, the same age, in fact, as her fictional heroine Elizabeth Bennet. After an early rejection by the publisher Cadell who had not even read it, Austen’s novel was finally bought by Egerton in 1812 for £110. It was published in late January 1813 in a small edition of approximately 1500 copies and sold for 18 shillings in boards. In a letter to her sister Cassandra on 29 January 1813, Austen writes of receiving her copy of the newly publishing novel (her “own darling child”), and while acknowledging its few errors, she expresses her feelings toward its heroine as such: “I must confess that I think her as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print, & how I shall be able to tolerate those who do not like her at least, I do not know.” Gilson A3; Grolier English 69; Keynes 3; Sadleir 62b. (3)

Estimate: $30,000 – $50,000 – SOLD: $68,500 (incl buyer’s premium)

***********************

Lot 86: Presentation copy of Emma. Provenance: Anne Sharp (1776-1853) “Anne Sharp” in vol. 1 and “A. Sharp” in vol. 2 and 3.

Lot Description:

One of twelve presentation copies recorded in the publisher’s archives and presented to Jane Austen’s “excellent kind friend”: the only presentation copy given to a personal friend of the author.

In a letter to the publisher John Murray dated 11 December 1815, Austen noted that she would “subjoin a list of those persons, to whom I must trouble you to forward a Set each, when the Work is out; – all unbound, with From the Authoress, in the first page”. Most of these copies were for members of Austen’s family. David Gilson in his bibliography of Austen lists these presentation copies, based on information in John Murray’s records, as follows:

- two to Hans Place, London (presumably for Jane Austen and Henry Austen)

- Countess of Morley

- Rev. J.S. Clarke (the Prince Regent’s librarian)

- J. Leigh Perrot (the author’s uncle)

- two for Mrs Austen

- Captain Austen (presumed to be Charles Austen)

- Rev. J. Austen

- H.F. Austen (presumed to be Francis)

- Miss Knight (the author’s favourite niece Fanny Knight)

- Miss Sharpe [sic]

Anne Sharp (1776-1853) was Fanny-Catherine Knight’s governess at Godmersham in Kent from 1804 to 1806. She resigned due to ill-health and then held a number of subsequent positions as governess and lady’s companion. Deirdre Le Faye notes that by 1823 she was running her own boarding-school for girls in Liverpool (see Jane Austen’s Letters, third edition, 1995, p. 572). She retired in 1841 and died in 1853.

In 1809 Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra Austen that “Miss Sharpe… is born, poor thing! to struggle with Evil…” Four years later Jane wrote to Cassandra that “…I have more of such sweet flattery from Miss Sharp! – She is an excellent kind friend” (which may refer to Anne Sharp’s opinion of Pride and Prejudice). It is known that Anne Sharp thought Mansfield Park “excellent” but she preferred Pride and Prejudice and rated Emma “between the two” (see Jane Austen’s Letters, third edition, 1995, p. 573).

There is one known extant letter from Jane Austen to Anne Sharp, dated 22 May 1817. She is addressed as “my dearest Anne”. After Jane Austen’s death, Cassandra Austen wrote to Anne Sharp on 28 July 1817 sending a “lock of hair you wish for, and I add a pair of clasps which she sometimes wore and a small bodkin which she had had in constant use for more than twenty years”.

“In Miss Sharp she found a truly compatible spirit… Jane took to her at once, and formed a lasting relationship with her… [she occupied] a unique position as the necessary, intelligent friend” (Claire Tomalin, Jane Austen: A Life, 2000).

Anne Sharp is known to have visited Chawton on at least two occasions: in June 1815 and in August-September 1820. Deirdre Le Faye notes that James-Edward Austen-Leigh described her as “horridly affected but rather amusing” (see Jane Austen’s Letters, third edition, 1995, p.573)

Estimate: 150,000-200,000 GBP* UPDATE: UNSOLD

[*Now this confuses me: this copy of Anne Sharp’s Emma sold at Bonhams for a record £180,000 in 2008, and was subsequently sold to an undisclosed buyer for £325,000. in 2010 [see my post here and here on these sales] – I have got to hit the calculator to see what’s up with this…]

************************

Also in this sale:

Lot 87: Austen, Jane. Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. John Murray, 1818.

Lot Description:

A set of Austen’s posthumously published novels in an attractive binding to a contemporary design. It appears that this set was the property of the Revd Fulwar-Craven Fowle (1764-1840). He was a pupil of Rev. George Austen at Steventon between 1778 and 1781. He is occasionally mentioned in Austen’s letters; it appears he participated in a game of vingt-un in 1801 and sent a brace of pheasants in 1815. Fulwar-Craven Fowle’s brother, Thomas (1765-1797) had been engaged to Cassandra Austen in 1792.

Deirdre Le Faye notes that he had “an impatient and rather irascible nature” and “did not bother to read anything of Emma except the first and last chapters, because he had heard it was not interesting” (see Jane Austen’s Letters, 1995, p. 525).

Estimate: 4,000 – 6,000 GBP UPDATE: UNSOLD

**********************

And a few from Austen’s Circle I could not resist reporting on: these are all in the Swann Auction on November 20th – lots of other finds, so take a look:

Swann Sale 2295 Lot 40

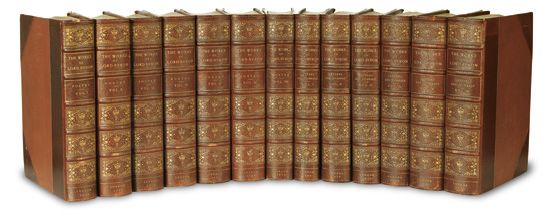

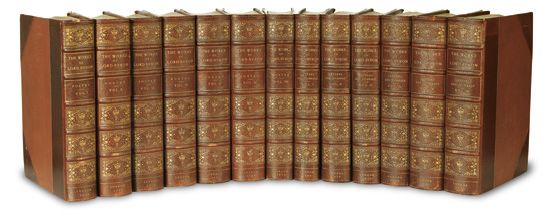

BYRON, LORD GEORGE GORDON NOEL. Works. 13 volumes. Titles in red and black. Illustrated throughout with full page plate engravings. 4to, contemporary 1/4 brown crushed morocco, spines handsomely tooled and lettered in gilt in compartments, shelfwear to board extremities with some exposure, corners bumped; top edges gilt, others uncut. London, 1898-1904

Estimate $1,000-1,500 SOLD: $1200. (incl buyer’s premium)

limited edition, number 97 of 250 sets initialed by the publisher. This set includes a tipped-in ALS (8vo, one folded sheet. April 7, 1892) by the editor of this edition, Ernest Hartley Coleridge, the grandson of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, to a Mr. Tours[?], recounting a lecture he had recently given in Minneapolis.

********************

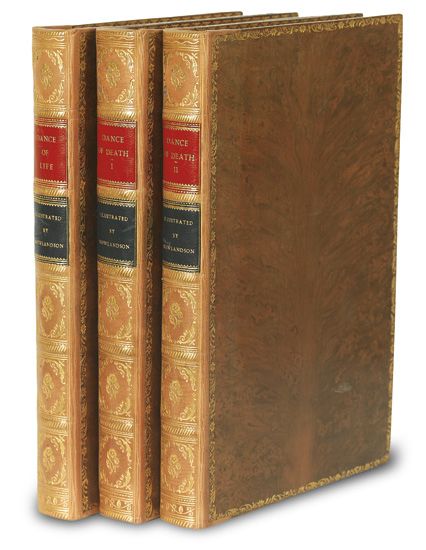

Swann Sale 2295 Lot 204:

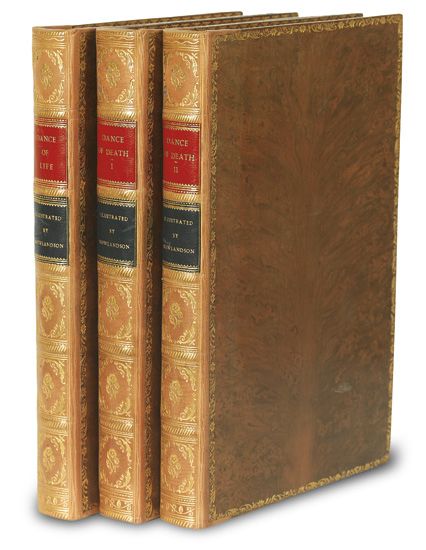

(ROWLANDSON, THOMAS.) The English Dance of Death. 2 volumes. * The Dance of Life. Together, 3 volumes. Engraved colored title-page and 37 hand-colored engraved plates in each volume of the Dance of Death, 25 hand-colored plates in the Dance of Life, by Rowlandson. Tall 8vo, later full tree calf gilt, spines tooled in gilt in 6 compartments with morocco lettering pieces in 2, rebacked; top edges gilt; occasional offsetting to text from plates and spotting to preliminaries; leather bookplates of Stephen M. Dryfoos mounted to front pastedown of 2 volumes; the whole slipcased together. London: R. Ackerman, 1815-16; 1817

Estimate $1,000-1,500 – SOLD: $3600. (incl buyer’s premium)

first editions in fine condition. “Indispensable to any Rowlandson collection, one of the essential pivots of any colour plate library, being one of the main works of Rowlandson”–(Tooley 410-411); Hardie 172; Abbey Life, 263-264; Prideaux 332; Grolier, Rowlandson 32.

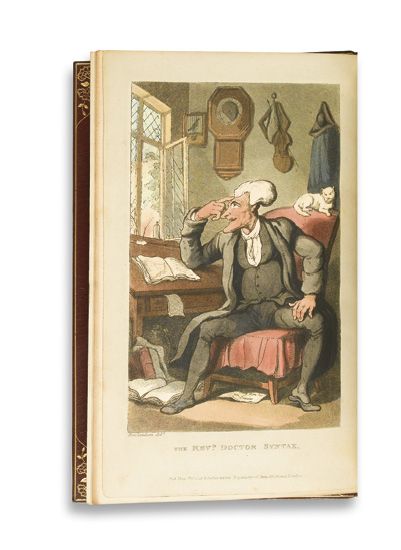

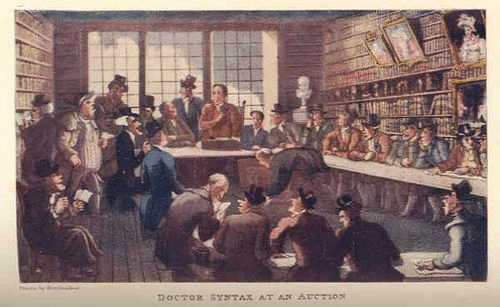

Swann Sale 2295 Lot 205:

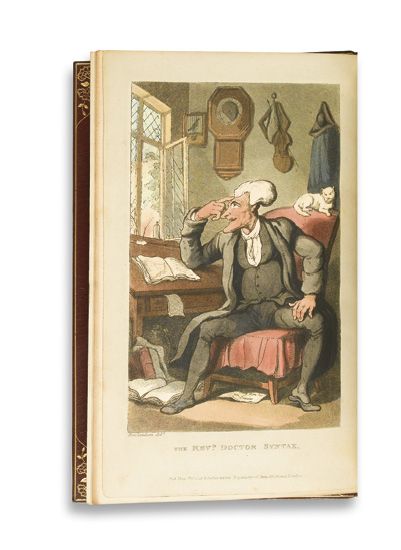

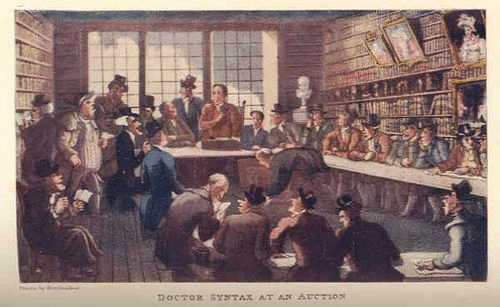

ROWLANDSON, THOMAS.) [Combe, William.] The Tour of Doctor Syntax, in Search of the Picturesque * In Search of Consolation * In Search of a Wife. Together, 3 volumes. Colored aquatint frontispiece in each volume, volumes 1 and 3 with additional aquatint title-page, and 75 colored plates by Rowlandson, colored vignette at end of vol. 3. Large 8vo, uniform full crimson crushed morocco blocked in gilt with corner floral ornaments, spines richly gilt in 4 compartments, titles in 2; turn-ins; by Root & Son, top edges gilt; bookplates of Edward B. Krumbhaar (vol. 1 only) and Christopher Heublein Perot (with his autograph). first edition in book form, second state, handsomely bound. London: R. Ackerman, 1812-20-(21)

ROWLANDSON, THOMAS.) [Combe, William.] The Tour of Doctor Syntax, in Search of the Picturesque * In Search of Consolation * In Search of a Wife. Together, 3 volumes. Colored aquatint frontispiece in each volume, volumes 1 and 3 with additional aquatint title-page, and 75 colored plates by Rowlandson, colored vignette at end of vol. 3. Large 8vo, uniform full crimson crushed morocco blocked in gilt with corner floral ornaments, spines richly gilt in 4 compartments, titles in 2; turn-ins; by Root & Son, top edges gilt; bookplates of Edward B. Krumbhaar (vol. 1 only) and Christopher Heublein Perot (with his autograph). first edition in book form, second state, handsomely bound. London: R. Ackerman, 1812-20-(21)

Estimate $600-900 – SOLD: $960. (incl buyer’s premium)

***************************

And despite my love of Austen, I do periodically enter the 20th century [sometimes the 21st!] and I still harbor my great admiration and love of John Steinbeck, so this I share because it is so rare and lovely to behold:

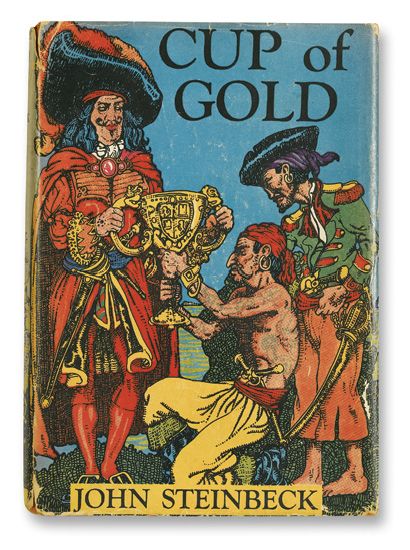

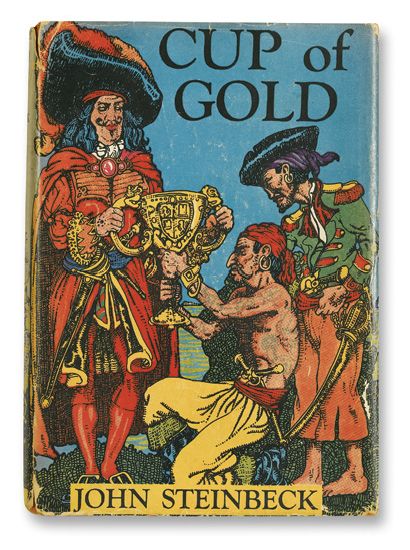

Swann Sale 2295 Lot 234 John Steinbeck. Cup of Gold.

STEINBECK, JOHN. Cup of Gold. 8vo, original yellow cloth lettered in black; pictorial dust jacket, spine panel evenly faded with minor chipping to ends with slight loss of a few letters, light rubbing along folds, small rubber inkstamp on front flap; bookplate with name obscured in black pen on front pastedown. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1929

Estimate $8,000-12,000 – SOLD: $14,400 (incl buyer’s premium)

scarce first edition, first issue of steinbeck’s first book with the McBride publisher imprint and “First Published, August 1929” on copyright page. Jacket flap corners evenly clipped as issued with “$2.50” printed price present. The publisher printed only 2476 copies, 939 of which were remaindered as unbound sheets and evidently sold to Covici-Friede who issued them with new preliminaries, preface, binding, and jacket in 1936. Variant copy (no priority) with the top edges unstained. Goldstone-Payne A1.a.

**********************

All images are from the respective auction houses with thanks.

Have fun browsing, and bidding if you wish!

c2012 Jane Austen in Vermont