Dear Readers: I welcome today my good friend Chris Sandrawich, who has posted here before on all things Jane Austen and the Regency world. This post on “Looking for Pemberley” was originally published in the JAS Midlands annual publications Transactions (No. 24, 2013), so I am honored to include it here on the blog where it might get a well-deserved wider readership. Chris’s usual insights and wit would, I believe, even delight our not-for-dull-elves Jane. Hope you enjoy it as much as I have – please comment below with any thoughts or questions you might have for Chris. [Please note that I have maintained Chris’s British spelling and punctuation!]

******

Looking for Pemberley

by Christopher Sandrawich

This article, in the nature of a ‘Quest’, is meant to half serious and half fun, and I apologise in advance for any difficulty in working out which half is which. It is a doomed quest because Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy along with Pemberley are all fictional and I apologise if any of your illusions have just been shattered. In “Looking for Pemberley” I was also diverted from this topic firstly by the River Trent and then by the Rutland Arms in Bakewell and so both will feature very largely in what I have to say.

I confess to being absolutely certain when I began this research that the popular choice of Chatsworth would not prove a very realistic proposition. However, I tried to keep an open mind. It fails primarily on economic grounds. Chatsworth is a palace, like Blenheim Palace or Warwick Castle. It is obviously the home of an aristocrat, with a very large income needed to run it. Our hero, Darcy is just plain “Mr”, but he is alluded to as someone who could be, “reasonably looked up to as one of the most illustrious personages in this land” by Mr Collins who likes to get his facts right, and so there is some room for doubt. We’ll see as this paper mirrors the trail of research I followed, that my view has, “been shifting about pretty much” like Elizabeth says in her explanation to Jane concerning her varying feelings about Wickham and Darcy. However, Jane Austen when creating her fiction had a perfect right to have none, one or a dozen gentlemen’s country homes in mind.

We have a few pointers on how Jane Austen found material for her novels. Gaye King, a former Chairman of The Jane Austen Society Midlands, discovered that Jane Austen stayed with her cousin the Rev Edward Cooper and his family, at Hamstall Ridware in Staffordshire, directly after visiting Stoneleigh Abbey. We can match

- Colonel Brandon’s Delaford in Sense and Sensibility with the Parsonage at Hamstall Ridware,

- Stoneleigh Abbey itself with Northanger Abbey and

- Stoneleigh Abbey’s chapel with that described in Mansfield Park and found in Mr Rushworth’s country home Sotherton. The landscaper Repton is the only one mentioned in any of the books and he worked on Stoneleigh Abbey and is the landscaper suggested for Sotherton.

Also, we have character’s names. Anyone who has read Sense and Sensibility will be interested in hearing that in addition to Colonel Brandon’s Delaford with its great garden walls, dovecote and stewponds matching Edward Cooper’s Rectory we have people known to, or friends of, the Coopers: Ferrars spelt with two “e’s” but still with an ‘F’, Dashwood, Palmer, and Jennings. Also, the Austens would have passed through Middleton on their journey from Stoneleigh Abbey in Warwickshire to Hamstall, and in addition Lord Middleton was a distant relation of Mrs Austen and she, herself, was named after the sister of the first Lord Middleton – Cassandra Willoughby. There we have six characters in the book straight off.

So Jane Austen has a proven track record, just like other novelists, of borrowing scenes and people from her memory when writing her novels and with the places mentioned above we have it on record that she visited them. Did our Jane go into Derbyshire? This is a good question and one which we will consider.

Rebecca

Rebecca may seem an odd place to start but I have my motives. Daphne du Maurier wrote Rebecca which was published in 1938 when she was in Alexandria, Egypt, where her husband was posted. What a lot of people do not know is that before she went to Egypt, Daphne du Maurier was travelling in Derbyshire with an Aunt, on her Father’s side, and she had sat up late one night in her hotel bedroom reading Pride and Prejudice.

Rebecca may seem an odd place to start but I have my motives. Daphne du Maurier wrote Rebecca which was published in 1938 when she was in Alexandria, Egypt, where her husband was posted. What a lot of people do not know is that before she went to Egypt, Daphne du Maurier was travelling in Derbyshire with an Aunt, on her Father’s side, and she had sat up late one night in her hotel bedroom reading Pride and Prejudice.

When she joined her Aunt for breakfast next morning, just as coffee was being poured, she said, “Last night I dreamt I went to Pemberley again”, but her Aunt who was hard-of-hearing and had lived in the far east, replied, “What was that dear, Manderley?” thinking no doubt of the similarity with the road to Mandalay . . . . . . . and so one of the great opening lines of a novel was born, “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again”, and Daphne, borrowing a napkin from the maid, wrote it down there and then.

So we can see that the closeness in spelling, and the shape of the word, between Manderley and Pemberley is not just co-incidental after all. I owe this information to my Uncle Jim whose best friend Eric’s mother Edith was the very lady pouring the coffee and passing napkins as a maid in that very same hotel.

Now if you suggest that I have just made all this up, as indeed you might, then I may reply as did Pooh-Bah in the Mikado, “Merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic veri-similitude to a bald and unconvincing narrative.” And I hope to avoid molten lead, as he was promised, for my pains. I fully expect that if this news spreads far and wide that plaques on hotel walls all over Derbyshire will appear claiming they were the very hotel where Daphne stayed and that they have her copy of Pride and Prejudice left by the bedside to prove it. Just why I have been involving us all in a flight of fancy will hopefully become clear later. People make things up you know!

As I mentioned above Rebecca was published in 1938 and was then adapted for film in 1940.

Pride and Prejudice

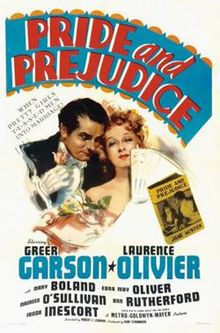

Pride and Prejudice was published two hundred years ago in 1813. Helen Jerome adapted it for the stage in 1935, and a Broadway musical First Impressions sprang from that. Helen Jerome’s adaptation was used again in 1940 for the film starring Laurence Olivier as Darcy, and a much too mature Greer Garson, as Elizabeth.

Pride and Prejudice was published two hundred years ago in 1813. Helen Jerome adapted it for the stage in 1935, and a Broadway musical First Impressions sprang from that. Helen Jerome’s adaptation was used again in 1940 for the film starring Laurence Olivier as Darcy, and a much too mature Greer Garson, as Elizabeth.

We won’t find Pemberley on a 1930’s Broadway stage and we can look in vain at the MGM film for it too. The nearest we get is an indoor scene were Bingley, distracted by his sister’s disparaging remarks about Jane and Elizabeth, plays a false shot and rips Darcy’s billiard table cloth. The whole room at Pemberley, as well as Meryton and Longbourn, were the product of the work of carpenters on MGM’s Hollywood studio lots. This adaptation did not even include the Gardiners.

TV Miniseries: Darcy and Elizabeth

After this film we have a glut of Television Miniseries appearing in the 1950’s and 1960’s (one in Italian and one by the Dutch which I shall skip over) and we do have interesting UK pairings for Darcy and Miss Elizabeth Bennet:

- 1952 Peter Cushing and Daphne Slater

- 1958 Alan Badel and Jane Downs

- 1967 Lewis Fiander and Celia Bannerman

Which, I believe, are all BBC productions: in those days ITV saw a limited audience for expensive to produce “costume-drama”, and as all the action on TV takes place in-doors we have no large buildings to show.

Peter Cushing photograph

We have not time to see them all but I could not resist finding a picture of Peter Cushing suitably dressed for his part of Darcy, which he would have played when 39 years of age.

Notable points emerging from the Outside

We are going to look at houses used in TV adaptations and in films. It will be interesting to compare the features presented by these choices with the novel’s description so when you view the houses try and put a mental tick against any point in favour of the house as a reliable model for Pemberley.

- Pemberley stood on the opposite side of a valley when first seen

- Large handsome stone building

- Standing well on rising ground

- Backed by a ridge of high woody hills

- In front a stream of some natural importance (that) has swelled into greater

- Without any artificial appearance

- They descended the hill crossed the bridge and drove up to the front door

Notable points emerging from the Inside

Inside from a window Lizzy Bennet’s prospect was

- The hill, crowned with wood from which they had descended receiving increased abruptness from the distance

- The river, the trees scattered along its banks

- The winding of the valley as far as she could trace

So, what we should be looking for is a house that matches as many of these ten key points as possible. Many of them only manage one, and we begin with:

Renishaw Hall

Renishaw Hall, in Derbyshire, was used as Pemberley for the 1980 BBC TV adaptation starring David Rintoul as Darcy and Elizabeth Garvie as Lizzy Bennet. The Sitwell fortune was made as colliery owners and ironmasters from the 17th to the 20th centuries, and Renishaw Hall has been the Sitwell family home for 350 years. The Bingley sisters can be as “sniffy” as they like about money arising ‘from trade’, and be hypocritical when doing it, but most of the aristocratic families had land and capital and they used old money for trade to make new money. The beautiful gardens you can see, including an Italianate garden, are open to the public.

Lyme Hall

Lyme Hall, Disley, is in Cheshire, and was used as Pemberley in the now quite famous 1995 BBC adaptation starring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth (which lady can ever forget his wet shirt). The house is the largest in Cheshire and is now owned by the National Trust. It had been in the Leigh family’s possession from 1388 until 1948.

The clever angle of the TV camera, as the Gardiner’s carriage stops and Lizzy takes her first look at “Pemberley”, made the stretch of water in front of the house look as much like a river as possible but it is of course more accurately described as ‘a large pond’.

Wilton House

For the 2005 P&P Wilton House near Salisbury in Wiltshire was used for many of the interior scenes (photograph by John Goodall).

Wilton House is situated near Salisbury in Wiltshire. It has been the country seat of the Earls of Pembroke for over 400 years. Now when you look at this house you may be wondering in which Pride and Prejudice you have seen it. Well, you haven’t seen the outside view BUT when Elizabeth and the Gardiners go into Lyme Hall they are seen inside Wilton House instead. A typical illusion pulled off with ease by TV and filmmakers and unless you are familiar with these homes you might never know.

There is a clue to this “switch” for the very observant; when Elizabeth, at the front of the house, takes in the view outside from the window the “lake” has trees along its nearside whereas Lyme Park does not.

Chatsworth House

Chatsworth House in Derbyshire is one of England’s most famous country homes and is owned by the Duke of Devonshire. Chatsworth was used as Pemberley in the 2005 film version starring Matthew Macfadyen as Darcy and Keira Knightley as Elizabeth Bennet.

Chatsworth House in the 18th C

Chatsworth House in the 18th Century an oil painting by William Marlow (1740 – 1813)

This painting (by William Marlow) gets us as close to seeing how Chatsworth looked when the 6th Duke inherited Chatsworth in 1811. Earlier works show bare-headed hill tops behind and so you will notice that there has been a lot of tree planting on the higher ground. We can see that the terrain Chatsworth stands in seems more sharply rising than the others.

So is Chatsworth Pemberley? Well let’s take a closer look at the 6th Duke and remember that Chatsworth is not really a house at all but like Blenheim, it is a Palace. Could Darcy on only £10,000 yearly income (even if it was very likely more as Mrs Bennet cheerfully speculates) manage such a home? It is difficult if not impossible to imagine how this level of income compares to today’s standards as lifestyles have changed so much. If we look at the RPI then £10,000 looks like only £500,000 in today’s purchasing power but if instead we look at the growth in earnings then £10,000 gets close to £8,000,000 so you can see the difficulties. Take your pick, but if a Curate could manage on £50pa then £10,000 is relative wealth two centuries ago.

A popular myth these days is that Darcy was one of the richest people in England. Afraid not, if he was on only £10,000 yearly, Jane’s brother Edward, adopted by the Knight family, had an income of £15,000pa and mere farmers to be found everywhere could have incomes of £10,000 to £40,000pa.

Louis Simond a Frenchman living in New York with his English wife toured England in 1811 – 12 and wrote an interesting sharply observed journal, which is full of facts and figures. He quotes the value of farmland in England at the time as 40/- to 45/- an acre for rent. Now if you worked the land you were expecting a profit so an acre would actually yield a larger income than the rents.

William Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858) – Thomas Lawrence

The 6th Duke owned 3 houses in fashionable London and many great estates in England and one in Ireland with a combined size of 200,000 acres. In Derbyshire he had 83,000 acres. Now not all the Duke’s land would be useable farmland and he would have had hills, woods and boggy ground eating into his farming income. But let us not forget that his powerful ancestors were amongst the first-comers and all the estates were set in favourable local conditions; so an estimate of 50% of his lands being utilised for farming could actually be conservative. Taking the mid-value of Louis Simond’s range and this estimate of the 6th Duke’s farming lands we can estimate his income as over £200,000pa.

Having done this exercise it is most disappointing to find that the Duke’s income for the period was assessed as only £70,000 yearly. Donald Greene quotes this on page 316 and gives his source as David Cannadine’s book, “The Landowner as Millionaire: The Finances of the Dukes of Devonshire”. This £70,000 yearly, after various mortgages and jointures were paid, left him with only with “a clear” £26,000 pa. Where might the discrepancy be? After all, if only £70,000 is drawn from over 200,000 acres then we conclude that only one-sixth of the land was rented for farming leaving five-sixths unutilised which seems untenable as a proposition and seems very unlikely behaviour from a Duke encumbered with debts not to instruct his servants to maximise his farming income.

The Duke’s estates were large and widespread and he would have to rely on stewards and many others in the management of these estates, so I am reminded of the second of Mr Bennet’s remarks to Jane on her engagement to Bingley. “You are each of you so complying, that nothing will ever be resolved on; so easy, that every servant will cheat you; and so generous, that you will always exceed your income.” But “cheating” on this massive scale seems unlikely as well, as how could such a small group of servants disguise, hide or profit from this wealth without drawing attention to themselves. So for me the suggested shortfall in income remains a mystery.

Harewood House

Harewood House is near Leeds in West Yorkshire and it was built from 1759 to 1771 for wealthy trader Edwin Lascelles, 1st Baron Harewood, and is still home to the Lascelles family. It was used as Pemberley in the ITV series “Lost in Austen” starring Jemima Roper as the ‘lost girl’ who eventually swops fates with Elizabeth, played by Gemma Arterton, and gets to marry Darcy played by Elliot Cowan. I personally really enjoyed the series, fanciful though it was.

How are your mental scores or ticks for the various houses going? Well we have run out of houses to look at as shown on TV and Film but we are still on our quest, and Chatsworth for me, is the only one we have seen which matches the novel’s description.

My next step is to look at the thoughts on “Where is Pemberley” amongst many eminent authors and scholars who were giving this subject a lot of thought in the 20th Century and who are now sadly no longer with us.

Elizabeth Jenkins

Elizabeth Jenkins died in 2010 aged 104, and she was a very distinguished novelist and historian and whose research for Jane Austen A Biography published in 1938 makes it still a very widely regarded work.

Elizabeth Jenkins died in 2010 aged 104, and she was a very distinguished novelist and historian and whose research for Jane Austen A Biography published in 1938 makes it still a very widely regarded work.

In 1958 she saw, in the Rutland Arms, Bakewell, a Notice making claims about Jane Austen staying in a room there whilst revising her novel Pride and Prejudice in 1811. She was “taken aback by these statements” and she could not get the author, Elizabeth Davie, who claimed the Bakewell: Official Guide, and by inference Mr V R Cockerton who wrote the introduction which Ms Davie quotes from pretty much word for word, as a reliable source for her claims, to retract them over exchanges lasting 6 or 7 years on and off. Elizabeth Jenkins never did get hold of a copy of the Bakewell Official Guide and in turn pursue Mr Cockerton, which is unfortunate as I have found all trails now run cold.

It is well worth mentioning that the latest Official Guide to Bakewell now says under a photo of the Rutland Hotel, and I quote, “William Wordsworth and J M W Turner were among the famous who visited the hotel. Jane Austen, contrary to popular story, did not; Pride and Prejudice was not written here and she is not known to have visited Derbyshire.” If you visit the Rutland Arms as I did only this year and enquire you will be confidently assured that Jane Austen stayed there and that there is a Notice about it that anyone can view. Hotel Staff do not know who wrote the notice, or that its original source was out-of-date editions of the Official Guide to Bakewell. They are further unaware that the same Guide now flatly refutes this assertion. They remain blissfully ignorant, but are very nice about it.

Getting back to the fifty year old dispute between Elizabeth Jenkins and Elizabeth Davie, the impasse reached led to Elizabeth Jenkins publishing an article in the JAS Report 1965 supported by the whole Jane Austen Society Committee rebutting the Notice’s claims saying they are entirely without foundation.

Strong stuff; but what exactly did the Notice say? Let’s look at the Rutland Arms.

Rutland Arms: Bakewell

Here is a side-view of the hotel in Bakewell called the Rutland Arms and it seems hardly likely to be the centre of a major literary controversy. Behind those walls we can find what the Notice says, and despite Elizabeth Jenkins best efforts it is still there?

The Notice was originally displayed right outside Bedroom No 2 (in the photo first find the door, then the window above; now go to the window on the left and you have Bedroom No 2). The Notice is now sited in the Reception area, and I write it out and put some stress on the contentious parts which will be discussed later:

In this room in the year 1811, Jane Austen revised the manuscript of her famous book “Pride and Prejudice”. It had been written in 1797, but Jane Austen who travelled in Derbyshire in 1811 chose to introduce the beauty spots of the Peak into her novel. The Rutland Arms Hotel was built in 1804, and while staying in this new and comfortable inn we have reason to believe that Miss Austen visited Chatsworth only three miles away and was so impressed by its beauty and grandeur that she made it the background for Pemberley, the home of the proud and handsome Mr Darcy hero of “Pride and Prejudice”.

The small town of “Lambton” mentioned in the novel is easily identifiable as Bakewell, and any visitor driving thence to Chatsworth must immediately be struck by Miss Austen’s faithful portrayal of the scene —— the “large handsome stone building, standing well on rising ground and backed by a ridge of woody hills”. There it is today, exactly as Jane Austen saw it all those long years ago.

Elizabeth Bennet heroine of the story had returned to the inn to dress for dinner, when the sound of the carriage drew her to the window. She saw a curricle driving up the street, undoubtedly Matlock Street, which these windows overlook, and presently she heard a quick foot upon the stair, the very staircase outside this door.

So, when visiting this hotel and staying in this room, remember that it is the scene of two of the most romantic passages in” Pride and Prejudice” and “Pride and Prejudice” must surely take its place among the most famous novels in the English Language.

Rutland Arms Brochure

It is possibly all for the best that Elizabeth Jenkins did not see the new brochure, because there is more. In the 1960’s the inn was owned by Stretton’s Derby Brewers Ltd, but the last time I looked it was owned by David Donegan, a retired solicitor. The brochure says (and I could only see the on-line version as they were waiting for a fresh package from their printers), and hang onto your hats while I quote from it,

“The Rutland has played host to several celebrated guests in its long history. Jane Austen stayed here in 1811 while revising her novel ”Pride and Prejudice”, using her room as the background for two scenes in the book and engraving sketches in the glass, still visible today”

The idea that Jane Austen would etch something on the windows of an Inn I find simply startling, and wonder just how this new information has come to light since the original Official Guide and the Notice. It seems obvious that the Hotel have not read the current Official Guide or remember hearing from Elizabeth Jenkins.

Objections to the Notice

Elizabeth Jenkins attacked the Notice on three main issues:

[ 1 ] She recited all of the reasons already mentioned why a Palace like Chatsworth is outside Darcy’s league, although she conceded the similarities in appearance, but she counters that there are in England many other houses that are a reasonable fit for ‘Pemberley’ too.

[ 2 ] Bakewell is NOT Lambton. A careful reading of the novel reveals that the Gardiners and Elizabeth are staying in Bakewell and when discussing their next step to visit Mrs Gardiner’s friends in Lambton they choose a route so as to see Pemberley on their way.

We will identify where Lambton, a fictitious Town might be later, but the novel indicates a three mile plus journey from Bakewell to Pemberley and then a five and a bit mile stretch to Lambton from there. We can have some fun at the Film and TV Adaptations’ expense now as some of them share this confusion between Bakewell and Lambton and the relative distances.

In the Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson film they neatly avoid all issues by omitting the Gardiners and the trip to Derbyshire altogether.

In the David Rintoul and Elizabeth Garvie TV Adaptation Lizzy is seen reading Jane’s letters revealing Lydia’s elopement while in their rooms at the Inn in Lambton and snatching up her hat and shawl she is seen running out of the room and then onto the approaches to Pemberley and into the House. This sequence gives the idea that this is no big deal and Elizabeth is only slightly breathless. Now I know that Elizabeth Bennet is fit, but five miles across undulating country – in the height of mid-summer – and encumbered with a long dress and petticoats and all the while clutching her letters! Suspend disbelief if you can.

This running is catching. In the Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth version we have the Gardiners already staying in Lambton, so the rationalé behind their visit to Pemberley no longer holds. But leaving that aside, when Mrs Gardiner mentions Lambton we see Darcy’s eyes light up and he describes how, when a young boy, he ran to the village green in Lambton to a tree by the smithy every day in the horse-chestnut season. I think that bit isn’t in the book because Jane Austen would reckon no boy of sense runs over ten miles daily to get conkers when he could get all he could carry within a few hundred yards of home. Unless, of course, stealing the village boys’ conkers was his aim.

In the Keira Knightley film version her Aunt and Uncle, from whom she was temporarily separated, inexplicably leave her behind at Pemberley, which seems excessively harsh treatment for not ‘keeping-up’. Lizzy refuses Darcy’s help with transport and says she’ll walk. She has never been to Lambton in her life let alone to Pemberley and to this part of Derbyshire but she boldly sets off across five miles of rough country beginning with crossing the Derwent and climbing out of the steep valley Chatsworth is in. The film shows her crossing fields and not following any path. Not only did she mystically pick exactly the right direction but without any roads or signposts to help she unerringly finds The Rose and Crown in a small town in the middle of nowhere.

Sorry, for the diversion, back to Elizabeth Jenkins and her next point.

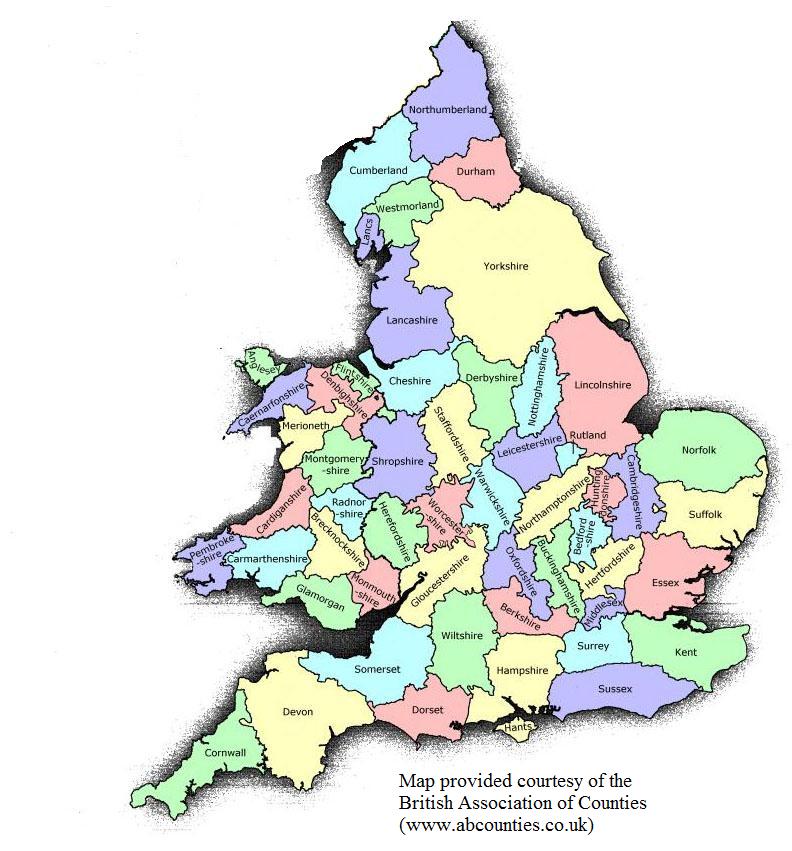

[ 3 ] She consulted the foremost authority at that time on all things Austen, Dr R W Chapman at Oxford with the question of Austen touring Derbyshire. He replied, “no evidence that she was ever north of the Trent”.

That was enough for Elizabeth Jenkins but some other smaller details in the Notice took my eye and I’ll share them with you.

[ 4 ] Two of the most romantic scenes in the novel! Well I do not think so. Let’s have a look at Bedroom No 2 which is where the visits occur. The room is very small but it has to be this room as it is adjacent to the stairs, and it is believed to have been permanently connected to the room next along, from which it is now divided by doors, and used as a Reception Room. It will help if we mentally ignore the décor and remove the bed. I can also imagine the sucking in of breath over teeth for any builder asked to enlarge a room that has two outside walls, one wall leading onto a landing and the last wall being almost all chimney breast for the large fireplace downstairs which was there when the hotel was built. I asked. So by the time we put in a table large enough for six along with chairs it will look cramped in this half of the reception room. Of course, as Jane Austen was making it all up, and if using the Rutland Arms as her model, then all she had to do was ‘imagine’ it large enough.

In the novel it holds Elizabeth with her Aunt and Uncle, although Ms Davie clearly leaves out the Gardiners in her depiction, and when the curricle arrives it rapidly fills up, first with Darcy and his sister, Georgiana, and then Bingley who joins them afterwards. A fraught and tense introductory meeting, yes; but not the stuff of romance.

The only other meeting taking place would be when Jane’s letters about Lydia’s elopement with Wickham have upset Elizabeth, and Darcy unexpectedly arrives and gives what help and comfort he can until the Gardiners return. For most of the time Darcy and Elizabeth are both very much preoccupied and caught up in their private thoughts and concerns. Romantic? Hardly; when he leaves Elizabeth never expects to see Darcy again!

[ 5 ] She heard Darcy’s quick foot on the stairs. The novel does not mention this but it does with Bingley’s arrival, when it is “Bingley’s quick step was heard on the stairs.”

[ 6 ] My last problem with the Notice is over ‘line of sight’. Here we have a view from the window, which is not the one you saw at the side of  the Rutland Arms as this window looks out of the front of the hotel. Elizabeth Davie has Lizzy Bennet noticing the curricle arriving, and it would help considerably if the street you can see outside was Matlock Street. The Devil is in the detail they say. The street outside, running towards the front of the hotel, is Rutland Square and that is definitely the one you take to get to Chatsworth House which is to the east of Bakewell. Matlock Street is the A6 running broadly north to south and, apart from the first few yards, it is well out of sight and bending away from the right-hand side of this window. Matlock Street unsurprisingly goes south to Matlock and getting further away from Chatsworth with every yard.

the Rutland Arms as this window looks out of the front of the hotel. Elizabeth Davie has Lizzy Bennet noticing the curricle arriving, and it would help considerably if the street you can see outside was Matlock Street. The Devil is in the detail they say. The street outside, running towards the front of the hotel, is Rutland Square and that is definitely the one you take to get to Chatsworth House which is to the east of Bakewell. Matlock Street is the A6 running broadly north to south and, apart from the first few yards, it is well out of sight and bending away from the right-hand side of this window. Matlock Street unsurprisingly goes south to Matlock and getting further away from Chatsworth with every yard.

Now we must remember that Georgiana only arrived with a large party in time for a late breakfast and they arrive to see Elizabeth before dinner, so that means Georgiana has only had a brief time to eat, change and collect herself before getting into the curricle with her brother. It would be unreasonable to suppose that she would have wanted to go sightseeing, or take a detour. So for Elizabeth Davie to be right, and for Darcy’s curricle to be coming up Matlock Street, we must accept the unlikely premise that Darcy has completely lost his way within three miles of his birthplace and home.

By the by, there are etchings on the bottom three frames of glass but you cannot see them in this photograph, although they are visible to the naked eye. They looked random and of the “Kilroy was here” variety. None of them seem remotely connected to Jane Austen, and which one, or many, the Hotel Brochure has in mind as Jane Austen’s artwork is not known to the staff we asked.

There is a big danger that when finding a lot of Ms Davie’s statements failing to stand up to close scrutiny that we cast doubt over all of them. Without looking at anything else, and without any supporting evidence anyway, it is reasonable already to be inclined to disbelieve, or doubt, all the other assertions made by Elizabeth Davie. However, some of them may be true, but which ones?

When I first read Dr Chapman’s reply it struck me as an odd choice of words: to say that someone definitely did not cross a particular river. Other ideas came as I was considering the novel. It also seemed that the Gardiners and Elizabeth took an odd route from Meryton to Derbyshire.

Gardiner’s route to Derbyshire

Here is a diagram showing the major points mentioned as being included in their journey: Oxford, Blenheim, Warwick, Kenelworth, Birmingham and finally Chatsworth, and I’ve connected the dots to emphasise the directions taken as they zagged and zigged across England. Their journey has always struck me as odd even when we think of the large houses to view along the route: Blenheim Palace, Warwick Castle, Stoneleigh Abbey and eventually Chatsworth. Does the mention of Chatsworth in the novel, by the way, serve as a clue to Jane Austen wishing to disguise it’s modelling for Pemberley, or is she ruling it out by making clear that Pemberley and Chatsworth are two separate places? This is a good question without a satisfactory answer.

Here is a diagram showing the major points mentioned as being included in their journey: Oxford, Blenheim, Warwick, Kenelworth, Birmingham and finally Chatsworth, and I’ve connected the dots to emphasise the directions taken as they zagged and zigged across England. Their journey has always struck me as odd even when we think of the large houses to view along the route: Blenheim Palace, Warwick Castle, Stoneleigh Abbey and eventually Chatsworth. Does the mention of Chatsworth in the novel, by the way, serve as a clue to Jane Austen wishing to disguise it’s modelling for Pemberley, or is she ruling it out by making clear that Pemberley and Chatsworth are two separate places? This is a good question without a satisfactory answer.

I digress; back to the odd journey. It’s the last lurch to Birmingham that always confused me. There is no stated reason to go there to view a large house, and it is unlikely that there was one. I found that I began to think again about R W Chapman’s remark and the importance given to the Trent, in conjunction with this journey.

Well what I found out about the River Trent surprised me. Two hundred years ago it was the natural boundary between the north and south of England. Also, “Trent” is a Gaelic word suggesting “severe flooding” and the crossing points for the Trent were by fords, except for a bridge, often in poor repair, at Burton. The other natural feature to add to the Trent’s sheer size and power is that the Trent like the Severn is tidal and has a “bore”; so twice a day there is a surging three to five foot wave coming upstream.

When I was researching for a talk on communications and I looked at how bad weather affected carriages I was struck by the utterance of one seasoned traveller:

“Give me a collision, a broken axle, and an overturn, a runaway team, a drunken coachman, snowstorms howling tempests . . . . . . . . . . but heaven preserve us from floods.”

And I wondered if the initial lurch west of nearly 70 miles to Oxfordshire and the last lurch mainly west of 20 miles to Birmingham was for no other reason than to put the travellers as far WEST as possible where the Trent would have the least amount of water flowing in it and be as far from the sea and the effects of the bore as possible. Jane Austen knew that her audience would expect any north-bound traveller to be wary of floods when crossing the Trent, and the usual way to avoid problems was to cross at Burton where there had been a bridge since, it is suggested, Roman times. Now First Impressions, the original name for Pride and Prejudice was first written in 1797 and so I looked for a reason why Jane Austen might think that the Gardiners would not wish to cross the Great Bridge at Burton which also means going from east to west as the Trent is flowing north at that point and so going to Birmingham would have been a much longer way around.

We should take note of the description given by a Mr Plot around 1700 of an ancient claim to distinction of the Great Bridge being, “the most notorious piece of work of a civil public building in the county or perhaps in England” and that the River Trent divided into three separate channels at Burton and the bridge had 34 arches spanning over 500 yards with water running through. It went in a series of curves as well. The Great Bridge must have been quite a sight.

Also owing to a sudden thaw on 10th February 1795 the Trent rose higher than it had been known before and no mail or wagon passed in or out of the town for two days. Many parts of the bridge were damaged and on Friday 13th February 1795 one of the arches fell in. The website British History On-line mentions regular floods at Burton and significantly has three occurring in the 1790’s. Now as the preceding one was 1771 and the next 1830, then we must assume these three mentions of floods were significant rather than just the regular minor seasonal flooding of the Trent that was just to be expected. Major floods in the 1790’s may have influenced Jane Austen’s thoughts about crossing the Trent at Burton and she might have been influenced by all these reports of difficulties and fairly negative news. Lots of large floods which would swamp the land around Burton and the bridge may have actually still been under on-going repair when she wrote her first drafts. Although these problems may well have diminished by the time Jane Austen revised the book for publishing over ten years later she may have felt there was no need to alter this part.

A Route Avoiding Burton?

As we have already mentioned Jane Austen together with her sister Cassandra and her Mother visited Jane’s cousin Edward Cooper Rector at St Michael and All Angels at Hamstall Ridware in Staffordshire. They had been staying in Stoneleigh Abbey with their relations the wealthy Leigh family, where they would have visited Kenilworth Castle and Warwick Castle, as both were only a few miles away. Their visit was made in 1806 and we know from her diaries that Edward Cooper’s Mother-in-law, Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys (a friend of Mrs Austen), visited in 1805 and her diaries show a tour was made into Derbyshire to see The Peak, Matlock and Dovedale. So, why not view Chatsworth while they were there?

Before we leap, as I did, to an instant conclusion that a repeat visit in the following year must have been made by the Austens and Coopers, I have Deidre le Faye to thank for the report that within one week of the Austens’ arrival all eight of the Cooper children went down with whooping cough. As their visit only lasted five weeks it seems unlikely that any such visit could have been managed unless they went straight away which is very unlikely. However, they had all the time they wished to talk about the earlier trip and discuss it with maps, magazines and books of reference. Jane Austen could have found out everything she needed to know about Chatsworth for her novel from the Coopers. This may well just be speculation but it seems more probable than just possible.

It also explains, to me at least, why the Gardiners took their route through Birmingham, which was at that time a noisy, dirty rapidly sprawling and major manufacturing centre and hardly a tourist attraction. However, if you come to it from Kenilworth it lines up with the road north through Lichfield to Hamstall Ridware and an easy crossing of the Trent, which is probably the way the Austens went. Jane Austen has a habit of using her practical experience to flavour her novels. She also knew how to get to Derbyshire from Hamstall by following the Cooper’s route north towards Uttoxeter and then Ashbourne and Debyshire.

For Elizabeth to get back at a rush following news of Lydia’s escapades and in the timings allowed by the novel and the relative speeds (8 mph in summer means the 150 or so miles would take just over 16 hours) of the carriages of the day with regular changes of horses and only one overnight stop they must have gone back by a more direct route and chanced the crossing of the River Trent at Burton. Look at me! Discussing a journey only ever made on paper!

Willersley Castle

Elizabeth Jenkins mentions during her long demolition job on the Notice that the Duke of Devonshire’s family had their own views on which house in the neighbourhood would be a good model for Pemberley. She says,”Sir William Makins has been told by Mary, Duchess of Devonshire, that in the Chatsworth neighbourhood it used to be said that Willersley, near Cromford, was the original of Pemberley.”

The Rev Mr R Ward who published one of the early 19th century Guides to the Peak of Derbyshire gave descriptions of both Chatsworth and Willersley Castle, and it is more than possible that Jane Austen would have had access to this guide, making a northern tour unnecessary. In The Rev Ward’s description of Willersley Castle he mentions the winding river at the front of the house – beyond it is seen a lawn on the farther side and on a very elevated part of which stands Willersley Castle, backed by high ground and wood. Ward then describes a stone bridge with three arches, and goes on to say that behind this and further to the east, rises a very elevated woody country.

Willersley Castle, which is now a Christian Guild Hotel, was built in the late 18th Century by the industrialist Sir Richard Arkwright. It is sited at Cromford on the River Derwent and stands on the slopes of “Wild Cat Tor” which is 400 feet above sea level. I found it interesting that the Wikipedia Page for Willersley Castle says he bought the estate from Thomas Hallet Hodges for £8,864 in 1782. However, the Wikipedia Page on Sir Richard Arkwright says he paid £20,000 to William Nightingale (Florence Nightingale’s father) in 1788. I’ve mentioned the inconsistency to Wikipedia ages ago but I can see no movement to correct either page. When I mentioned this curious discrepancy to the hotel staff they compounded the confusion by saying it was thought the land was sold by the 5th Duke of Devonshire.

When Sir Richard Arkwright died in 1792 he left £500,000, which at 5% interest on Government Securities would have generated an income of £25,000 pa. This puts him into Darcy’s league if a little better placed.

I have been to Willersley Castle and although many features are a good fit for Pemberley it has some drawbacks. It does not have a ‘picture gallery’ or a great staircase. If the house is viewed by carriage from the cliffs opposite then, without travelling many miles out of the way, there is no quick way down, other than a one-way plummet. There is also no way you can see the River Derwent from the ground floor of the Castle as the ground drops away quickly on a convex slope. But in a novel it doesn’t have to fit exactly, does it? Artistic licence?

Painting of Willersley Castle

When Kevin George, the General Manager at this hotel, supplied information he said this painting was the work of, “a chap called Whittle” and Thomas Whittle is the right period and this is his style – but I am no art expert – and I show it because it confirms what is possible with a little artistic licence because a painting or a book does not have to stick to facts if the artist does not wish to.

Where’s “Wild Cat Tor” gone? A physical feature you can see from miles away.

Donald Greene

Donald Greene

It was at this point that I came across Donald Greene and found he had written an essay entitled, “The Original of Pemberley?” Donald Greene was aged 83 when he died in 1997 and he was a literary critic, English Professor and scholar of British literature particularly the eighteenth century period, and was a noted expert on Samuel Johnson. Greene was Canadian by birth and took his MA at University College London and seems to have spent his teaching and academic life at various American universities.

His essay demonstrates meticulous research and I found myself following in the footsteps of a master as he danced through the available information on this subject including what I have already seen from Elizabeth Jenkins and Elizabeth Davie. I do not have time to go through all that Donald Greene has to say, these are only selected highlights.

He agrees with the demolition job done by Elizabeth Jenkins on Elizabeth Davie, but points out that she said little about the claim that “The description of Pemberley is a faithful portrait of Chatsworth” and I agree with Donald Greene that this is “the acid test”.

The first item he establishes is that the fictitious name Lambton is in all probability Old Brampton, as it was then known, a village five miles east of Chatsworth. Now it is part of the urban sprawl to the west of the centre of Chesterfield but in 1812 it was a distinct and separate community.

As we can see from this map the road from Bakewell to Old Brampton takes us close to Chatsworth.

Donald Greene is not easily deflected from testing the narrative describing Pemberley against Chatsworth’s physical features. However, before we get into a comparison between Jane Austen’s description of Pemberley and its grounds I would like you to see an extract from the novel at the start of Chapter 43, as this description is all important, you need to have it fresh in your minds:

Elizabeth, as they drove along, watched for the first appearance of Pemberley Woods with some perturbation; and when at length they turned in at the lodge, her spirits were in a high flutter.

The park was very large, and contained great variety of ground. They entered it in one of its lowest points, and drove for some time through a beautiful wood stretching over a wide extent.

Elizabeth’s mind was too full for conversation, but she saw and admired every remarkable spot and point of view. They gradually ascended for half a mile, and then found themselves at the top of a considerable eminence, where the wood ceased, and the eye was instantly caught by Pemberley House, situated on the opposite side of a valley, into which the road with some abruptness wound. It was a large, handsome stone building, standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills; and in front a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal nor falsely adorned. Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place for which nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by an awkward taste. They were all of them warm in their admiration; and at that moment she felt that to be mistress of Pemberley might be something!

They descended the hill, crossed the bridge, and drove to the door; and, while examining the nearer aspect of the house, all her apprehensions of meeting its owner returned. She dreaded lest the chambermaid had been mistaken. On applying to see the place, they were admitted into the hall; and Elizabeth, as they waited for the housekeeper, had leisure to wonder at her being where she was.

The housekeeper came; a respectable-looking elderly woman, much less fine, and more civil, than she had any notion of finding her. They followed her into the dining-parlour. It was a large, well-proportioned room, handsomely fitted up. Elizabeth, after slightly surveying it, went to a window to enjoy its prospect. The hill, crowned with wood, from which they had descended, receiving increased abruptness from the distance, was a beautiful object. Every disposition of the ground was good; and she looked on the whole scene — the river, the trees scattered on its banks, and the winding of the valley, as far as she could trace it — with delight.

Topography of Chatsworth

Greene suggests the actual route making use of detailed maps shown below. I will refer to key passages from the book and give you Greene’s remarks on the physical route. The correspondence is staggering, I assure you.

Chatsworth House with Hunting Tower (photograph by Paul Collins) used as Pemberley in the scenes for Joe Wright’s 2005 P&P

- Novel: they turned in at the lodge. Greene: the lodge is still there – a substantial 18th C stone building called Beeley Lodge which is 350 feet above sea level.

- Novel: They gradually ascended for half a mile, and then found themselves at the top of a considerable eminence where the wood ceased, and the eye was instantly caught by Pemberley House, situated on the opposite side of a valley. Greene: The road (B6012) here rises 150 feet to the 500 foot level at a “spur” and the wood indeed does still cease at this point “A” affording an impressive view of Chatsworth across the valley

- Novel: standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills; and in front a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance Greene: The steep slopes behind the house are densely wooded and there are two unobtrusive weirs that effect this “swelling” of the River Derwent at that point.

- Novel: They descended the hill, crossed the bridge, and drove to the door; Greene: The road does descend from this point to a lovely bridge built by James Paine in 1762 when the 4th Duke of Devonshire transformed Chatsworth by turning it to face the river instead of the hillside, and the entrance was then, as now, on the north.

- Novel: On applying to see the place, they were admitted into the hall . . . . . . The housekeeper came; . . . . . . . . . . . . . They followed her into the dining-parlour Greene: The ‘dining-parlour’ would have been what in the 19th Century was called the buffet room, the lower dining room or the morning room; it is now called the Lower Library, and is used by the present Duke and Duchess as their private sitting room.

- We now have the prospect from a window

- Novel: Elizabeth, after slightly surveying it, went to a window to enjoy its prospect. The hill, crowned with wood, from which they had descended, receiving increased abruptness from the distance, was a beautiful object. Every disposition of the ground was good; and she looked on the whole scene — the river, the trees scattered on its banks, and the winding of the valley, as far as she could trace it Greene: The windows of this room do face west, looking across the Derwent at the hill from which they had descended and the view or the river, trees and valley is exactly as Elizabeth describes.

There seems to be an exact match between Pemberley, as described through the eyes of the Gardiners and Elizabeth, with the actual layout and topography of Chatsworth’s grounds and Park. The description of what can be seen from inside the house, especially, does create the suspicion, a strong suspicion in my case, that Jane Austen actually saw, or closely questioned a keen observer who saw, what she describes through Elizabeth’s eyes. Therefore, we could conclude that Jane Austen, or someone she talked closely to, must have toured Chatsworth, but as nobody left any evidence, then we have no proof.

Wentworth Woodhouse

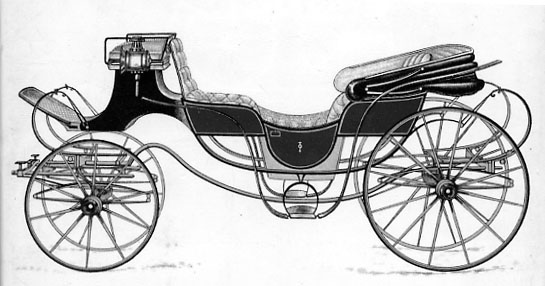

Wentworth Woodhouse is the largest private home in England, and with the longest frontage (606 feet long) or façade in Europe. At the 2013 JASNA AGM and Conference held at the end of September in Minneapolis with a theme devoted to Pride and Prejudice and all things Jane Austen, Professor Janine Barchus presented ideas on Wentworth Woodhouse being the model for Pemberley. It is a notion that has a lot going for it especially with the connection of names. It was owned by Earl Fitzwilliam and listed amongst his relations we have the D’Arcy’s an old aristocratic family from the north of England. However, I have my doubts based on geography. Wentworth Woodhouse is in Yorkshire, near Rotherham, and is therefore considerably more than 3 miles from Bakewell, and topography seems an issue again. Where is our rising ground, our stream in front, the thickly wooded hills steeply rising behind, a three-arched bridge to cross and finally stables to walk around the corner of the house from for Darcy to surprise his visitors on the lawn, these can all be looked for in vain. Then there is the question of size. Wentworth Woodhouse had a park of only 180 acres, although the Estate comprised an additional 15,000 acres. Pemberley has a Park ten miles around. As a circle this gives a diameter of just over three miles and an area of just over 5000 acres. If instead we made the Park square with edges 2.5 miles long the acreage becomes 4000 acres and still far too large for Wentworth Woodhouse. No Phaeton and pony required for a mere 180 acres which is just over a quarter of a square mile in area. So Wentworth Woodhouse is amongst the runners, but it is not my favourite.

Co-incidences and Similarities with Chatsworth

- When Elizabeth replies to Mrs Gardiner’s suggestion that they visit Pemberley her reply is, “She must own that she was tired of great houses; after going over so many, she really had no pleasure in fine carpets and satin curtains”. As Elizabeth had just been to Blenheim Palace, Warwick Castle and we suppose Stoneleigh Abbey then this comment places Pemberley as being in the same class. Jane Austen was very familiar with the distinctions between a “Great House” and a superior gentleman’s residence. Pemberley contains a Picture Gallery and a Great Staircase which are typically found in “Great Houses”, and are found in Chatsworth.

- When Elizabeth and her aunt return Georgiana’s visit they are shown into a saloon which might be the present Ante-Library (then the little dining room) at Chatsworth. Elizabeth is able to see a “prospect” of the Pemberley grounds not yet encountered, and the windows, “admitted a most refreshing view of the high woody hills, and of the beautiful oaks and Spanish chestnuts which were scattered over the intermediate lawn.” This room does look to the east, facing the hillside, and the trees described are still there.

- It really would be easier to buy Chatsworth/Pemberley than to find similar ground and build another

- Chatsworth has a large library that is the work of many generations

- The Palladian stables are exactly where they need to be to have Darcy appear round the corner from them

- They, Pemberley and Chatsworth, each have a park that is about ten miles around. There are very few houses in England with a Park that to go around you need a Phaeton and pony.

- Pemberley has a Great Staircase and a Picture Gallery, which together with the 5000 acres of Park make it too grand to be just a “superior gentleman’s residence” and very few houses fit this description as well as Chatsworth

- The route walked by the party fits the park and river at Chatsworth exactly.

- It is often said that Jane Austen, who was an avid follower of the theatre and its performers’ careers, based the looks, at least, of Elizabeth Bennet on the slim, athletic and attractively dark-eyed Dorethea Jordan who was mistress to the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV. They had ten children and never married but they were all well looked after. So Dorothy Jordan rose from the lower-classes to fascinate one of the most illustrious personages in the land!

- The 6th Duke was single, and “One of the most illustrious personages in this land” as described by Mr Collins in his letter to Mr Bennet. He was also the most eligible bachelor in England.

- His father, the 5th Duke, had just died so he inherited in 1811

- His father, the 5th Duke, was well known for having Georgiana and Elizabeth his wife and mistress living in the same house, Chatsworth. The two ladies apparently got along well for over twenty years of this, and could presumably tut tut to each other about illegitimate children appearing on all sides. However these French sounding goings on contrast well with Jane Austen giving Elizabeth the idea about her marriage to Darcy, when she fears that Lydia’s marriage to Wickham may have ruined its prospect, “But no such happy marriage could now teach the admiring multitude what connubial felicity really was” – Is this Jane Austen being typically ironic by comparing an idyllic marriage for the 6th Duke with the 5th Duke’s more complex arrangements?

- The 6th Duke’s mother had died some years earlier, as had Lady Anne Darcy.

- He had a sister called Georgiana

- His mother’s maiden name was Fitzwilliam, and as mentioned above Earl Fitzwilliam lived 25 miles east of Chatsworth at Wentworth Woodhouse. Jane Austen characters again: Capt Wentworth from Persuasion and Emma Woodhouse the principal character in

Did Jane Austen look out of that Lower Library window?

Well, although I am now inclined to think there is good circumstantial evidence for the notion I have to concede that there is absolutely no proof at all, only conjecture.

So, does Pemberley equal Chatsworth after all? I am more inclined to believe it is than when I started on this quest. We’ll never know for sure.

If only Jane Austen had etched something on the Duke of Devonshire’s windows in the Lower Library, as she was apparently prone to do!

Panoramic view of Chatsworth House and Park. An oil on canvas by Peter Tilemans (1684 – 1734) at the turn of the 17th/18th Century. Counting animals in the foreground shows the ideas of “picturesque” had not yet taken hold!

c2020 Jane Austen in Vermont, c2013 Chris Sandrawich