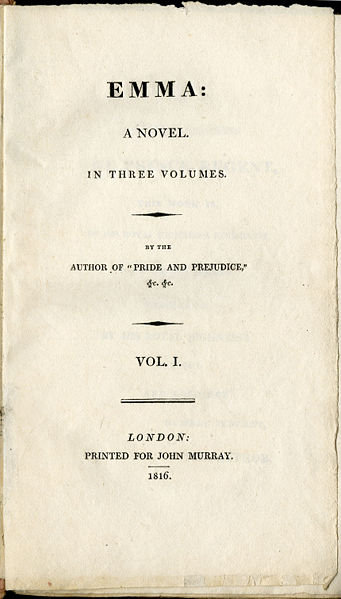

As part of Sarah Emsley’s upcoming three month-long celebration of Emma, “Emma in the Snow” beginning on December 23, 2015, I have written this post on its publishing history – an interesting tale gleaned from Austen’s Letters, Deirdre Le Faye’s Chronology, and other scholarly essays. Sarah will be re-blogging it, and we welcome your comments on either site. Emma was published in late December 1815, though the title page states 1816, and hence why there are celebrations both this year and next. I always have felt it appropriate that this book was published so close to Austen’s birthday on the 16th, and why I am posting this today, what would have been her 240th! And December brings to mind the very pivotal and humorous scene on Christmas Eve with Mr. Elton and Emma in the carriage – think snow – it shall be here soon enough!

Publishing Emma

Emma, Vol. 1 cover. London: Dent, 1898 (Mollands)

The most oft-quoted reference to Emma appears in her nephew James Edward Austen Leigh’s Memoir of 1870 where he writes: “She was very fond of Emma, but did not reckon her being a general favourite; for when commencing that work, she said, ‘I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.’” (Memoir, 140) And indeed, most of the controversy surrounding Emma, though considered by many to be her “most profound achievement,” (Fergus 14) has been the likeability of this title character.

One of the joys of reading Jane Austen’s letters is to discover the numerous references to her novels through the writing and publishing process – we all feel great disappointment that there are not more – but in the case of Emma, there are many such finds, almost all to do with its publication, and why perhaps we hang on this quote from the Memoir as Austen’s only personal comment about its creation. In writing up this interesting publishing history, I realize most of the best bits are in these letters as she negotiates with her new publisher John Murray, nurses her brother Henry through a near-death illness, visits the Prince Regent’s Librarian at Carlton House, learns that her niece Anna Lefroy has had a baby daughter and her brother Frank another son, works with the printers’ galleys of Emma, and edits Mansfield Park for a second edition. She has also at this time begun writing Persuasion (begun August 8, 1815 and finished August 6, 1816) – a great deal happens in these two months from October 4, 1815 when she leaves Chawton for London with Henry, and December 16th, when she returns! Emma is finally published on December 23rd and she begins keeping a record of its “opinions” henceforth.

I am going to present here a chronological accounting of Emma’s publication, interspersed with the letters – it is the only way to get a full sense of what was actually happening – her letters making us nearly over-the-shoulder voyeurs into these very packed two months of her life.…

Dates of composition: these are noted in Cassandra Austen’s memorandum (Minor Works, opp. 242): began January 21, 1814; finished March 29, 1815. Jan Fergus believes that she likely revised it until August when she began Persuasion (Fergus 5). She does not submit the manuscript to John Murray until late August or early September 1815.

But what of the backstory? There are no comments by Austen to the actual writing of Emma, but it is worth a look at what she was doing between January 1814 and March 1815 to tease out some interesting real-life correlations. In the “Introduction” to the 2005 Cambridge edition of Emma, the editors (Richard Cronin and Dorothy McMillan, ) note a number of various events during this time frame that perhaps in one way or another show up in the plot and characters of Emma. Le Faye’s Chronology and The Letters are invaluable here – here is a quick sampling:

- Austen visits Great Bookham, which is close to Box Hill and Leatherhead, considered the most likely model for Highbury.

- Miss Sharpe is now a governess in Yorkshire – Austen wishes for her employer to marry her has echoes in the story of Miss Taylor, later Mrs. Weston, and Jane Fairfax (see Ltr. 102, June 23,1814).

- Austen’s niece Anna marries Ben Lefroy on November 8, 1814 – perhaps why she names the baby in Emma “Anna” (though Mrs. Weston’s first name is Anne)

- Austen writes to her niece Fanny about whether or not she is in love with John Plumptre – we see this as Emma humorously debates with herself about whether or not she is in love with Frank Churchill (see Ltrs. 109 and 114).

- We have only to read her letter to Anna about the atmosphere of the Wen [London] to recall Mr. Woodhouse’s commentary on the air of London and Isabella’s staunch defense of their “superior” location in Brunswick Square. [see Ltr. 110. Nov 22, 1814]

Anna Lefroy – from the Memoir

Anna Lefroy – from the Memoir

- Austen is reading and critiquing her niece Anna’s novel – it is here we have the most information on Austen’s view of the writing process – and where she famously states: “…3 or 4 Families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on…” (Ltr. 107, Sept 9-18, 1814), which of course is exactly what Emma is all about. (See Cronin and McMillan, xxiii-xxv)

I will do a more detailed post on this backstory topic in the future, but now a return to the publishing adventure.

A house in Hans Place, London. similar to where

A house in Hans Place, London. similar to where

Henry Austen lived and Jane Austen visited

Source: Constance Hill, Jane Austen: Her Homes and Her Friends (1923)

October 4, 2015: Austen travels to London with her brother Henry, expecting to stay “a week or two” (Ltr. 120) and negotiations with her publisher begin. Her attempts to have Thomas Egerton publish a 2nd edition of Mansfield Park had been unsuccessful the previous year:

Austen had written on November 30, 1814: (Ltr. 114 to Fanny Knight)

“…it is not yet settled yet whether I do hazard a 2d Edition. We are to see Egerton today, when it will be probably determined. – People are more ready to borrow & praise, than to buy…”

John Murray. NPG-wikipedia

October 17, 1815: There is no definitive answer as to why Egerton did not choose to publish, but we do know that Austen submitted her Emma manuscript to the more prestigious John Murray the following year in late summer / early fall 1815. We know from the Chronology (514) that Henry and Jane visited Steventon unexpectedly Sept 3rd and stayed until the 5th – this may have been when Austen gave her “Emma” MS to Henry to deliver to Murray. In a letter dated Sept 29, 1815, Murray’s editor William Gifford writes: “Of ‘Emma’, I have nothing but good to say. I was sure of the author before you mentioned her.” It is believed that at this point Murray was hoping to purchase the copyright and have Gifford edit the manuscript for publication.

Kathryn Sutherland in her essay “Jane Austen’s Dealings with John Murray and His Firm” outlines further explanation as to when Murray may have been first approached by Austen. She has found in the Murray Archives an earlier letter from Gifford dated November 14, 1814 on his having read Pride and Prejudice. Sutherland supposes that Austen met with Murray in the November of 1814 year when in London negotiating with Egerton over the Mansfield Park 2nd edition. By the time Gifford writes his Sept. 1815 letter urging Murray to acquire Emma, as well as the copyrights of P&P and another novel, he is already familiar with and highly values her writings.

But Austen writes: [Ltr. 121 Oct 17, 1815]

“Mr. Murray’s Letter is come [dated Oct 15]; he is a Rogue of course, but a civil one. He offers £450 – but wants to have the Copyright of MP & S&S included. It will end in my publishing for myself I dare say. – He sends more praise however than I expected. It is an amusing Letter.”

So the decision is made to publish on commission, i.e. Austen takes on the expense of publishing, Murray takes 10% commission on all profits – Austen had learned her lesson in selling the copyright of Pride and Prejudice directly to Thomas Egerton for £110. But those who have looked into all the facts and figures of her profits and losses (see especially Fergus) surmise that she in this case would have done better to have sold the copyrights outright for the £450.

Henry’s illness: It is also in this letter of Oct 17th that Austen first makes note of Henry being ill – “Henry is not  quite well – a bilious attack with fever.” She continues the letter the next day with:

quite well – a bilious attack with fever.” She continues the letter the next day with:

“Henry’s illness is more serious than I expected. He has been in bed since three o’clock on Monday” and goes on to write about the physician Mr. Haden’s (though Austen spells it “Haydon”) opinions of the matter and the drawing of blood to lessen inflammation – “Henry is an excellent Patient, lies quietly in bed & is ready to swallow anything. Her lives upon Medicine, Tea and Barley water… he is in “the back room upstairs – & I am generally there also, working or writing.”

October 20, 1815: Henry Austen’s letter of October 20 or 21st is written – Austen kept a draft [Ltr. 122(A)(D)] with this heading:

“A Letter to Mr. Murray which Henry dictated a few days after his Illness began, & just before the severe Relapse which drew him into such Danger.”

Dear Sir

Severe Illness has confined me to my Bed ever since I received Yours of ye 15th – I cannot yet hold a pen, & employ an Amuensis [sic]. – The Politeness & Perspicuity of your Letter equally claim my earliest Exertion. – Your official opinion of the Merits of Emma, is very valuable & satisfactory. – Though I venture to differ occasionally from your Critique, yet I assure you the Quantum of your commendation rather exceeds than falls short of the Author’s expectation & my own. – The Terms you offer are so very inferior to what we had expected that I am apprehensive of having made some great Error in my Arithmetical Calculation. – On the subject of the expense & profit of publishing, you must be much better informed that I am; – but Documents in my possession appear to prove that the Sum offered by you, for the Copyright of Sense & Sensibility, Mansfield Park & Emma, is not equal to the Money which my Sister has actually cleared by one very moderate Edition of Mansfield Park – (You Yourself expressed astonishment that so small an Edit. of such a work should have been sent into the World) & a still smaller one of Sense & Sensibility…

I love this letter! – it shows Henry as a strong advocate for his sister, as well as quite the wit!

But succeeding days show Austen requesting a second doctor for Henry – this was likely Dr. Matthew Baillie, one of the Prince Regent’s medical advisors (Le Faye, Chron. 518) Austen begins to summon family members and Cassandra, James, and Edward all head for London; Cassandra will remain there with Jane until Nov 20th.

In the middle of all this, on October 20th, Anna Lefroy (James’s daughter) gives birth to a little girl named Anna-Jemina! And on the 30th Austen writes to her niece Caroline Austen (now 10 years old) about her own story in the making: she feels “not quite equal to taking up your Manuscript, but think I shall soon, & hope my detaining it so long will be no inconvenience.” [Ltr. 123, Oct 30, 1815]

November 3, 1815. A few days later we see Austen taking on the negotiating of Emma herself – she writes:

My Brother’s severe Illness has prevented his replying to Yours of Oct 15, on the subject of the MS of Emma, now in your hands – And as he is, though recovering, still in a state which we are fearful of harassing by Business & I am at the same time desirous of coming to some decision on the affair in question, I must request the favour of you to call on me here, on any day after the present that may suit you best, & at any hour in the Evening or any in the Morning except from Eleven to One. – A short conversation may perhaps do more that much Writing. [Ltr. 124, Nov 3, 1815]

We hear no more of the actual negotiations, but find that in mid-November Murray includes Emma in his list of publications in the press and “nearly ready for publication” – this November 1815 listing was found inserted in a copy of Helen Maria Williams’ A Narrative of the Events which have Taken Place in France (London: Murray, 1816) – Austen refers to this book in letter 127 (Nov 24, 1815) below (Gilson xxix).

November 8, 1815. Austen’s brother Frank’s 4th son, Herbert Grey, is born!

November 13, 1815 – The visit to Carlton House:

Carlton House, London

Sometime in early November, the Prince Regent’s physician tells Austen that he is aware she is the author of Pride and Prejudice, and “that the Prince [is] a great admirer of her novels and has read them often and kept a set of in every one of his residences; and he himself thought he ought to inform the Prince that Miss Austen was staying in London, and that the Prince [has] desired Mr Clarke, the librarian of Carlton House, to wait upon her.” (Memoir 105) And here we have one of the more interesting series of letters in the whole collection – insight into Austen’s life in London, her ready wit, the assuredness of her own talents, and the issue of the dedication of Emma to “His Royal Highness, The Prince Regent.”

AN ASIDE ~ the Austen – Clarke correspondence:

Carlton House Library

We know that Austen visited Carlton House and met with the librarian James Stanier Clarke on Monday the 13th – but alas! there is no account of it from her directly – how one would love to have heard her comments to her sister and Henry when she returned to Hans Place that day! – all we have is this letter of the 15th addressed to Clarke: [ Ltr. 125(D)]

Sir,

I must take the liberty of asking You a question – Among the many flattering attentions which I rec’d from you at Carlton House, on Monday last, was the Information of my being at liberty to dedicate any future Work to HRH the P.R. without the necessity of any Solicitation on my part. Such at least, I beleived to be your words; but as I am very anxious to be quite certain of what was intended, I intreat you to have the goodness to inform me how such a Permission is to be understood, & whether it is incumbent on me to shew my sense of the Honour, by inscribing the Work now in the Press, to H.R.H. – I sh’d be equally concerned to appear either presumptuous or Ungrateful.-

I am etc…

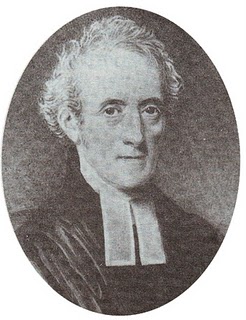

James Stanier Clarke – wikipedia

Clarke responded immediately:

It is certainly not incumbent on you to dedicate your work now in the Press to His Royal Highness: but if you wish to do the Regent that honour either now or at some future period, I am happy to send you that permission which need not require any more trouble or solicitation on your Part.

And then Clarke goes on to offer Austen writing advice!

Your late Works, Madam, and in particular Mansfield Park reflect the highest honour on your Genius & your Principles; in every new work your mind seems to increase its energy and powers of discrimination. The Regent has read & admired all your publications.

Accept my sincere thanks for the pleasure your Volumes have given me: in the perusal of them I felt a great inclination to write & say so. And I also dear Madam wished to be allowed to ask you, to delineate in some future Work the Habits of Life and Character and enthusiasm of a Clergyman – who should pass his time between the metropolis & the Country – who should be something like Beatties Minstrel… Neither Goldsmith – nor La Fontaine in his Tableau de Famille – have in my mind quite delineated an English Clergyman, at least of the present day – Fond of, & entirely engaged in Literature – no man’s Enemy but his own. Pray dear Madam think of these things…

P.S. I am going for about three weeks to Mr Henry Streatfields, Chiddingstone Sevenoaks – but hope on my return to have the honour of seeing you again. (Ltr. 125(A), Nov 16, 1815)

This lively correspondence between Austen and Clarke continued later in December upon Clarke’s return – Austen writes on December 11:

My Emma is now so near publication that I feel it right to assure you of my not having forgotten your kind recommendation of an early Copy for Cn H. [Carlton House] – & that I have Mr. Murray’s promise of its being sent to HRH. under cover to You, three days previous to the Work being really out.-

I must make use of this opportunity to thank you dear Sir, for the very high praise you bestow upon my other Novels – I am too vain to wish to convince you that you have praised them beyond their Merit.-

My greatest anxiety at present is that this 4th work shd not disgrace what was good in the others. But at this point I will do myself the justice to declare that whatever may be my wishes for its’ success, I am very strongly haunted by the idea that to those Readers who have preferred P&P, it will appear inferior in Wit, & to those who have preferred MP, very inferior in good Sense.

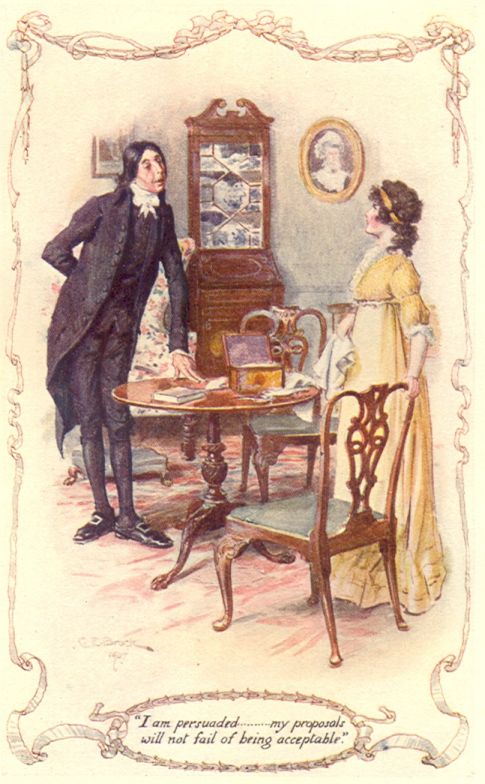

And here she addresses Clarke’s suggestions for her Clergyman:

I am quite honoured by your thinking me capable of drawing such a Clergyman as you gave the

CE Brock – Mr Collins (Mollands)

sketch of in your note of Nov: 16. But I assure you I am not. The Comic part of the Character I might be equal to, but not the Good, the Enthusiastic, the Literary. Such a Man’s Conversation must at times be on subjects of Science & Philosophy of which I know nothing – or at least be occasionally abundant in quotations & allusions which a Woman, who like me, knows only her own Mother-tongue & has read very little in that, would be totally without the power of giving. A Classical Education, or at any rate, a very extensive acquaintance with English Literature, Ancient & Modern, appears to me quite Indispensable for the person who wd do any justice to your Clergyman – And I think I may boast myself to be, with all possible Vanity, the most unlearned, & uninformed Female who ever dared to be an Authoress. (Ltr. 132(D), Dec 11, 1815)

Clarke writes again on Dec 21st or so thanking her for the copy of Emma which he has sent on to the Prince Regent: “I have read only a few pages which I very much admired – there is so much nature – and excellent description of Character in everything you describe.” He then goes on to again implore her to write about a Clergyman, in what sounds like a sort of autobiography of Himself! – then offers her a copy of his forthcoming book on James II, as well as the offer of the use of his small Cell and library at No. 37 Golden Square when she comes to Town – “I shall be most happy. There is a Maid Servant of mine always there.”

What an offer!!

In March, Clarke writes from Brighton sending the thanks of the Prince Regent for “the handsome copy of your last excellent Novel.” He then drops a few names (he is very good at name-dropping!) and suggests that her next work’s dedication should be to Prince Leopold: “any Historical Romance illustrative of the History of the august house of Cobourg, would just now be very interesting.”

Believe me at all times

Dear Miss Austen

Your obliged friend

J. S. Clarke

[Ltr. 138(A), Mar 27, 1816]

To which Austen responds after thanking him for his praises:

…You are very, very kind in your hints as to the sort of Composition which might recommend me at present, & I am fully sensible that an Historical Romance, founded on the House of Saxe Cobourg might be more to the purpose of Profit or Popularity, than such pictures of domestic L:ife in Country Villages I deal in – but I could no more write a Romance than an Epic Poem. – I could not sit seriously down to write a serious Romance under any other motive than to save my Life, & if it were indispensable for me to keep it up & never relax into laughing at myself or other people, I am sure I should be hung before I finished the first Chapter. – No – I must keep to my own style & go on in my own Way. And though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other.

I remain my dear Sir,

Your very much obliged & very sincere friend

J Austen

[Ltr. 138(D), April 1, 1816]

And that seems to be the last of their correspondence – we know Austen is deep into writing Persuasion at this point, and that Emma has received a number of good reviews and is selling well. I love this letter because again, it gives us rare insight into how she thought of herself as a writer, as well as a good slice of her self-deprecating irony. And Clarke is so clearly a portrait of Mr. Collins! – a character she wrote a full 10 years before! Austen must have had a good hearty laugh about his requesting her to write about a Clergyman – one wonders what Clarke’s view of Mr. Collins could possibly have been…

*****************

November 23, 1815: We now must return to the matter at hand – the publication of Emma – with several letters between her and Mr. Murray that show how involved she was in this process. Henry is gradually getting stronger and has written a letter to Murray on Nov 20th (Le Faye Chrono. 520) about the publishing delays, but we do not have a copy of this letter – Austen seems to be doing all the work with Murray herself from this point. Real life includes the visit of her niece Fanny who arrived on the 15th or 16th of November…and Cassandra returns to Chawton on the 20th.

To John Murray, November 23, 1815 [Ltr. 126]

My Brother’s note last Monday has been so fruitless, that I am afraid there can be little chance of my writing to any good effect; but yet I am so very much disappointed & vexed by the delays of the Printers that I cannot help begging to know whether there is no hope of their being quickened. – Instead of Work being ready by the end of the present month, it will hardly, at the rate we now proceed, be finished by the end of the next, and as I expect to leave London in early Decr, it is of consequence that no more time should be lost. Is it likely that the Printers will be influenced to greater Dispatch & Punctuality by knowing that the Work is to be dedicated, by Permission, to the Prince Regent? – If you can make circumstances operate, I shall be very glad…. (Austen then thanks Murray for the loan of a book to Henry)

November 24, 1815: It is in Austen’s next letter to Cassandra that we learn “a much better account of my affairs, which I know will be a great delight to you.”

Printing House – 18thc (eduscapes.com)

“I wrote to Mr Murray yesterday myself, & Henry wrote at the same time to Roworth [one of the printers]. Before the notes were out of the House I received three sheets, & an apology from R. We sent the notes however, & I had a most civil one in reply from Mr M. He is so very polite indeed, that it is quite overcoming. – The Printers have been waiting for Paper – the blame is thrown upon the Stationer – but he gives his word that I shall have no farther cause for dissatisfaction.” Murray loans them two books – the Miss Williams as noted above and a Walter Scott and she is “soothed & complimented into tolerable comfort.-”

…A Sheet come in this moment. 1st & 3rd vol. are now at 144. – 2d at 48. – I am sure you will like Particulars. – We are not to have the trouble of returning the Sheets to Mr Murray any longer, the Printer’s boys bring & carry. [Ltr. 127, Nov 24, 1815]

November 26, 1815: The next day is given over to shopping (from 11:30 – 4:00 for all manner of errands and the “miseries of Grafton House”) and on the 26th Austen writes of all these events and their purchases, then this about Emma:

I did mention the P.R. – in my note to Mr Murray, it brought me a fine compliment in return; whether it has done any other good I do now know, but Henry thought it worth trying. – The Printers continue to supply me very well, I am advanced in vol. 3 to my arra-root, upon which peculiar style of spelling, there is a modest qury? in the Margin. – I will not forget Anna’s arrow-root. – I hope you have told Martha of my first resolution of letting nobody know that I might dedicate &c – for fear of being obliged to do it – & that she is thoroughly convinced of my being influenced now by nothing but the most mercenary motives.

And she ends this long letter on visits, visitors, and Henry’s health with this comment on her brother Charles’s letter:

I have a great mind to send him all the twelve Copies which were to have been dispersed among my near Connections – beginning with the P.R. & ending with Countess Morley. [see below for a list of recipients] [Ltr. 128, Nov 26, 1815]

December 2, 1815: Emma is advertised in The Morning Post as being published in a few days, and Austen’s only mention of Emma in her letter of this day to Cassandra is: “It strikes me that I have no business to give the P. R. a Binding, but we will take Counsel upon the question.” (She does present him with a fine binding of Emma as her letters above to Clarke indicate; it cost her 24s!)

Emma – Prince Regent’s copy (Le Faye)

December 6, 1815: Emma is again advertised in The Morning Post as forthcoming.

December 10, 1815: The Observer advertises “On Saturday next will be published… EMMA.” (i.e. Dec 16 – but it does not appear on this date)

December 11, 1815: Austen writes another letter to John Murray.

As I find that Emma is advertized for publication as early as Saturday next, I think it best to lose no time in settling all that remains to be settled on the subject, & adopt this method of doing so, as involving the smallest tax on your time.-

In the first place, I beg you to understand that I leave the terms on which the Trade should be supplied with the work, entirely to your Judgement, entreating you to be guided in every such arrangement by your own experience of what is most likely to clear off the Edition rapidly. I shall be satisfied with whatever you feel to be best.-

The Title page must be, Emma, Dedicated by Permission to H. R. H. The Prince Regent. – And it is my particular wish that one Set should be completed & sent to H. R. H. two or three days before the Work is generally public – It should be sent under Cover to the Rev. J. S. Clarke, Librarian, Carlton House. – I shall subjoin a list of those persons, to whom I must trouble you to forward also a Set of each, when the Work is out; – all unbound, with From the Authoress, in the first page.

I return to you, with very many Thanks, the Books you have so obligingly supplied me with. – I am very sensible I assure you of the attention you have paid to my Convenience & amusement. – I return also, Mansfield Park, as ready for a 2d Edit: I beleive, as I can make it. – …. I wish you would have the goodness to send a line by the Bearer, stating the day on which the set will be ready for the Prince Regent. [Ltr. 130, Dec 11, 1815]

And another letter to Murray on the same day – he must have instantly dispatched a response to the above:

I am much obliged by your, and very happy to feel everything arranged to our mutual satisfaction. As to my direction about the title-page, it was arising from my ignorance only, and from my never having noticed the proper place for a dedication. I thank you for putting me right. Any deviation from what is actually done in such cases is the last thing I should wish for. I feel happy in having a friend to save me from the ill effect of my own blunder. [Ltr. 131C, Dec 11, 1815]

(And see her letter to Clarke on this date above claiming to be “the most unlearned, & uninformed Female who ever dared to be an Authoress.”)

December 16, 1815: Austen’s birthday! Emma is not published as advertised, and she leaves for Chawton as she notes in Letter 133 (Dec 14, 1815) “I leave Town early on Saturday…” – she has been in London for over two months, her stay lengthened by Henry’s illness and publishing delays.

December 16, 1815: Austen’s birthday! Emma is not published as advertised, and she leaves for Chawton as she notes in Letter 133 (Dec 14, 1815) “I leave Town early on Saturday…” – she has been in London for over two months, her stay lengthened by Henry’s illness and publishing delays.

There are no more letters until December 31, though Fanny Knight writes in her pocket-book on the 17th and the 22nd that she received a letter from Aunt Jane – more letters lost… (Le Faye Chrono. 524).

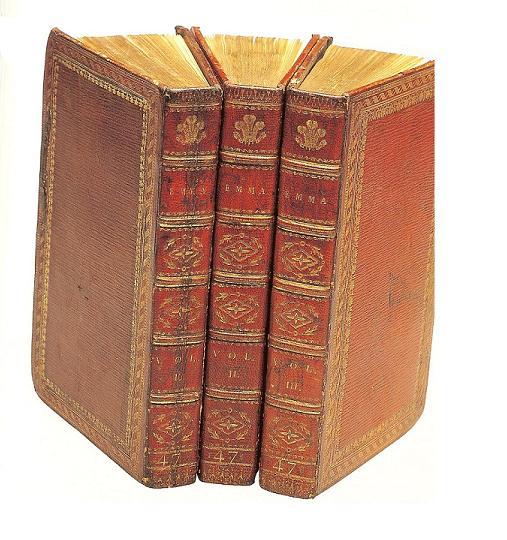

December 19, 1815: “Murray’s clerk enters details in the ledger regarding Emma: 2000 copies printed, 3 vols., price 1 guinea the set, title page dated 1816” – also includes Austen’s list of her 12 presentation copies (see below). Murray also gives a copy to Byron’s half-sister Augusta Leigh, and to Maria Edgeworth at Austen’s request. (Le Faye Chrono. 525)

December 21, 1815: The Morning Chronicle: Emma to be published “on Saturday next”

December 22, 1815: The Morning Chronicle: Emma to be published “Tomorrow”

December 23, 1815: The Morning Chronicle: Emma “PUBLISHED THIS DAY”

December 25, 1815: John Murray writes to Walter Scott requesting a review of Emma – this is published in March 1816 issue of the Quarterly Review.

“Have you any fancy to dash off an article on ‘Emma’? It wants incident and romance does it not? None of the author’s other novels have been noticed [in Murray’s ‘Quarterly Review’] and surely ‘Pride and Prejudice’ merits high commendation.” (Gilson 69)

December 27, 1815: the Countess of Morley, one of the recipients of a presentation copy, writes to Austen:

Countess of Morley – BBC

…I am already become intimate in the Woodhouse family, & feel that they will not amuse & interest me less than the Bennetts [sic], Bertrams, Norriss & all their admirable predecessors – I can give them no higher praise – [Ltr. 134(A), Dec 27, 1815] (though the Countess writes letters to others that she finds the book quite dull – more on this in another post!)

December 31, 1815: Austen responds to the Countess:

Madam,

Accept my Thanks for the honour of your note & for your kind disposition in favour of Emma. In my present state of doubt as to her reception in the World, it is particularly gratifying to me to receive so early an assurance of your Ladyship’s approbation. – It encourages me to depend on the same share of general good opinion which Emma’s Predecessors have experienced, & to believe that I have not yet – as almost every Writer of Fancy does sooner or later – overwritten myself… [Ltr. 134, Dec 31, 1815]

Early January 1816: Austen sends her copy of Emma to her niece Anna – and as she had with Pride & Prejudice in calling it “my own darling child,” compares her novel creation to the birth of a Anna’s baby:

My dear Anna,

As I wish very much to see your Jemina, I am sure you will like to see my Emma, & have therefore great pleasure in sending it for your perusal. Keep it as long as you chuse; it has been read by all here.-

Austen in late January also sends off a copy of Emma to her friend Catherine Ann Prowting, after the death of their mutual friend Mary Benn. [Ltr. 136, Jan ? 1816]

And then no letters at all until March 13 (Ltr. 137 to Caroline Austen) … but on February 19, 1816, Murray publishes the 2nd edition of Mansfield Park: 750 copies (Gilson 59):

In mid-march, Henry Austen’s bank fails, a catastrophic event for the family – Austen refers to it in her April 1, 1816 letter to Murray as “this late sad Event in Henrietta St.” And here in late March and early April we have the two letters noted above to and from James Stanier Clarke.

March 1816: the Quarterly Review (vol. 14, no. 27, dated October 1815) is published and contains Scott’s (though anonymous) review of Emma.

Sir Walter Scott – wikipedia

April 1, 1816: Austen to John Murray, returning his copy of the Quarterly Review –

I return you the Quarterly Review with many Thanks. The Authoress of Emma has no reason to think to complain of her treatment in it – except in the total omission of Mansfield Park. – I cannot but be very sorry that so clever a Man as the Reveiwer of Emma, should consider it as unworthy of being noticed, – You will be pleased to hear that IU have received the Prince’s Thanks for the handsome Copy I sent him of Emma. Whatever he may think of my share of the Work, Yours seems to have been quite right… [Ltr. 139, April 1, 1816]

February 20-21, 1817 [Ltr. 151]: the last mention of Emma in the letters is a thank you to Fanny for mentioning Mrs. C. Cage’s praise of Emma. Austen notes this in her “Opinions of Emma”:

A great many thanks for the loan of Emma, which I am delighted with. I like it better than any. Every character is thoroughly kept up. I must enjoy reading it again with Charles. Miss Bates is incomparable, but I was nearly killed with those precious treasures! They are Unique, & really with more fun that I can express. I am at Highbury all day, & I can’t help feeling I have just got into a new set of acquaintance. No one writes such good sense, & so very comfortable. [MW 439]

************

So Emma is released upon the world on December 23, 1815, with the following dedication, the only time Austen dedicated a novel to anyone (her juvenilia is all dedicated, amusingly so – worth a read in themselves!) – I think she bandies about “Royal Highness” a bit too much, perhaps her only way of disguising in plain sight her dislike of the man!

TO HIS

ROYAL HIGHNESS

THE PRINCE REGENT,

THIS WORK IS,

BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS’S PERMISSION,

MOST RESPECTFULLY

DEDICATED,

BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS’S

DUTIFUL

AND OBEDIENT

HUMBLE SERVANT,

THE AUTHOR

***********

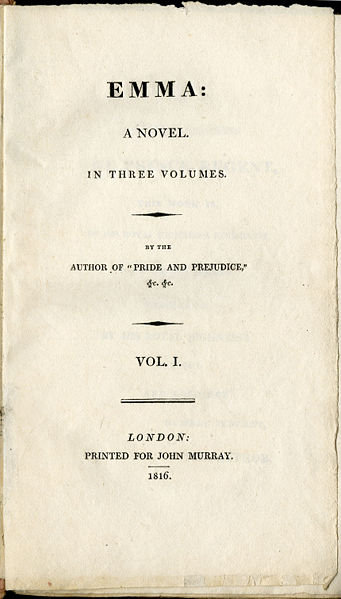

Here is how it looks in the 1816 American edition of Emma, the same as it did in the London 1st edition:

(Goucher College website)

**************

I repeat here the advertisements for Emma’s publication:

- Mid-November 1815, Murray includes Emma in his list of publications in the press and “nearly ready for publication”

- The Morning Post (Dec 2, 1815): “in a few days will be published…EMMA, a novel”

- The Morning Post (Dec 6, 1815): repeated the above

- The Observer (December 10, 1815): “On Saturday next will be published… EMMA.” (i.e. Dec 16 – but it does not appear on this date, Austen’s birthday).

- The Morning Chronicle (Dec 21, 1815): Emma to be published “on Saturday next”

- The Morning Chronicle (Dec 22, 1815): Emma to be published “Tomorrow”

- The Morning Chronicle (Dec 23, 1815): Emma “PUBLISHED THIS DAY”

- The Morning Post (Dec 29, 1815) – also advertises Emma as “This day published…”

The title page states 1816 – this was customary for books published at the end of the preceeding year. Note that Northanger Abbey and Persuasion were published in late December 1817, though the title page states 1818.

Presentation copies: (from Murray’s records)

- The Prince Regent: his was delivered to James Stanier Clarke on December 21, 1815, bound in full red morocco gilt at a cost of 24s – Clarke writes on its receipt: “You were very good to send me Emma – which I have in no respect deserved. It is gone to the Prince Regent. I have read only a few pages which I very much admired – there is so much nature – and excellent description of Character in everything you describe.” (Ltr. 132(A). Dec 21, 1815)

- Jane Austen

- Henry Austen

- Countess of Morley

- Rev. J. S. Clarke

- J. Leigh Perrot

- Mrs. Austen (2 copies)

- Captain Austen (likely Charles)

- Rev. J. Austen

- H. F. Austen (Frank)

- Miss Knight (Fanny)

- Miss Sharpe (governess / JA’s friend)

- Augusta Leigh (Byron’s half-sister), given by Murray

- Maria Edgeworth, as requested by Austen

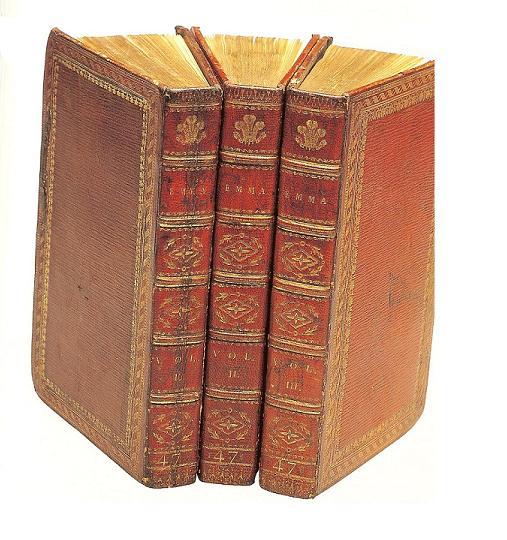

The Particulars:

- Published anonymously “By the Author of ‘Pride and Prejudice,’ etc, etc”

- Copies: 2000 were printed, the 3-volume set sold for £1.1s., more than was usual for a 3-volume novel. 1248 were sold by Oct 1816, and by 1820, 538 copies were remaindered at 2s each.

- Printers: C. Roworth (vols. 1 and 2); J. Moyes (vol. 3)

- Binding: grey-brown paper boards and spine, or blue-grey boards and grey-brown, grey-blue or off-white spine

A pristine 1st of Emma for sale last year for £100,000

A pristine 1st of Emma for sale last year for £100,000

at Lucius Books in York (Daily Mail, Dec 2014)

or it may have looked like this:

Pride & Prejudice 1st ed (1813) – National Library of Scotland

5. Profits: Murray published Emma on commission, but also published the second edition of Mansfield Park – as noted above, Austen had written to Murray from Hans Place on Dec 11, 1815: “I return also ‘Mansfield Park,’ as ready for a 2d edit: I believe, as I can make it-” this edition came out on February 19, 1816 but did not sell well – the losses on this reduced the profits on Emma (which were substantial at the likely total of £373) to £38.18 (Fergus). One issue contributing to lower profits was Murray’s use of more expensive paper.

6. No manuscript survives.

7. Later Publishing History: a brief summary

Emma (Philadelphia, 1816) – Goucher College

1st American Edition – the only such printed in Austen’s lifetime, but since it was never mentioned by her or her family, it was likely unknown to them.

Published by Mathew Carey of Philadelphia in 1816, this American edition was only discovered in 1939 when found listed in a bookshop catalogue. It is unknown how many copies were printed but this edition is very rare – Goucher College has a copy in their Alberta H. Burke Collection – and this year it is the subject of an exhibition. You can visit the website here: http://www.emmainamerica.org/

Published in two volumes, the first is available online at the Goucher website; Volume II will be available next year.

1st French translation (Paris: Feb 1816): titled La Nouvelle Emma, with the translator not noted.

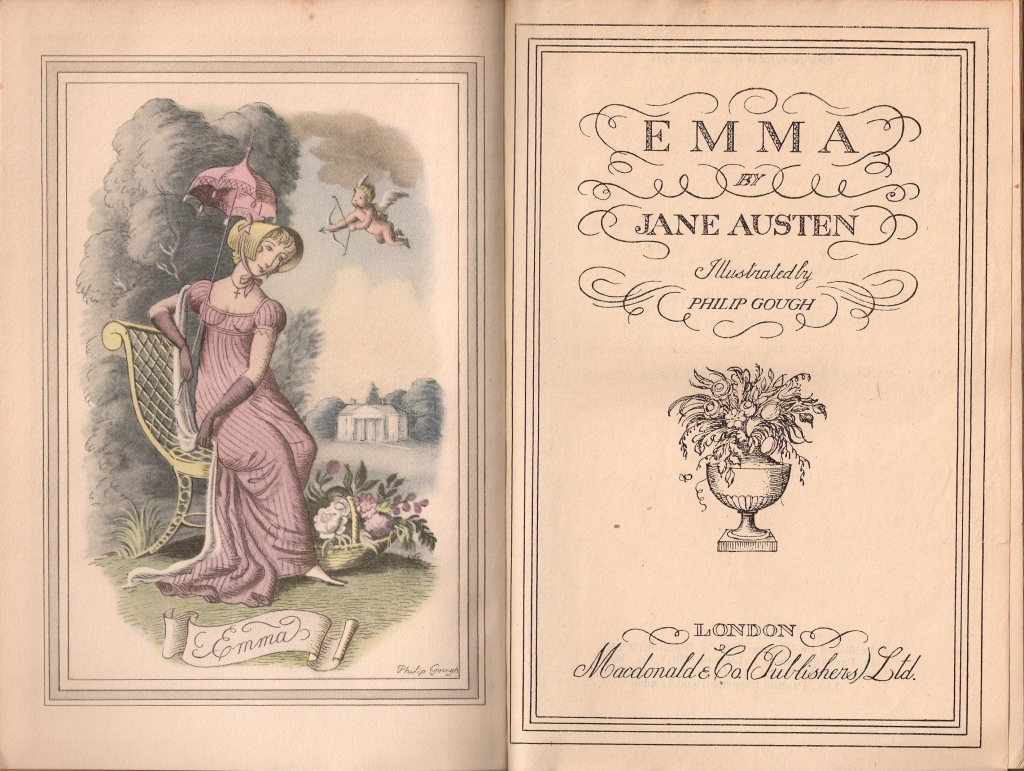

1st Bentley edition (1833): Richard Bentley purchased the copyrights of Austen’s novels from Henry and Cassandra for £210, with another £40 paid to Egerton for the copyright of P&P. He was to include them in his Standard Novels series. Sense and Sensibility was published on Dec 28, 1832 (t.p. states 1833), followed by Emma on Feb 27, 1833. This edition eliminated the Dedication to the Prince Regent for reasons unknown. There is an engraved frontispiece and title page vignette by William Greatbatch after George Pickering.

Emma, (Bentley, 1856 ed with same frontis as 1833 ed) – Andrew Cox Rare Books

8. Value today: First editions of Emma come up for auction periodically, prices all depending upon condition. In the original boards as published estimated values vary from $75,000 – 100,000; rebound in contemporary leather values average $35,000 – $50,000; modern re-bindings will fetch less. There are ten online at present, all rebound and varying from $17,000 – $45,000. The first American edition by Carey is rarely seen, though there is one right now online for $25,000. Of course online prices don’t tell the full tale – auction prices give us the true value at any given time – Emma in original boards sold for £30,000 at Sotheby’s in 2010, a rebound edition sold at Bonham’s in 2013 for $8500. In 2014, a nearly pristine copy in original boards sold for £48,050.

The Anne Sharp presentation copy noted above has been bandied about in recent years: it sold in 2008 for £180,000, then again in 2010 for £325,000. It was up for auction in December 2012 for an estimate of £150,000 – £200,000 but did not sell, and I do not know where it might be at present…

Anne Sharp presentation copy of Emma – Sotheby’s

Anne Sharp presentation copy of Emma – Sotheby’s

It does make one wonder what Jane Austen would think of all this!

************

For the 200 years since that December 23rd “THIS DAY PUBLISHED” there have been an abundance of Emmas brought into the world – with various printing fonts, interesting covers from the delightful to the ridiculous, and illustrations from all manner of artists – collecting them is a full-time job! But if we look back to that first edition with far less print to every page, no illustrations, and those rather dull covers, we have merely what Austen wrote, a tale of a matchmaking heroine who is at times hard to take. Austen knew her reading public and had, as we saw in the quote opening this post, her own concerns about Emma’s likeability in that larger world outside her own family circle. But of course that’s the point – surrounded in charades and puzzles and as P. D. James has pointed out, a detective story, a coterie of characters, some quite annoying, and a narrative technique that leaves you wondering who said or thought what, Austen gives us a nearly perfect novel, one that leaves you guessing right to the end, brilliantly portraying a very small world that mirrors the larger, all told with a heavy dose of irony. Who cannot delight in Mr. Woodhouse’s obsessions with his health and fears of anything sweet; or Miss Bates babblings of little nothings that of course tell us most of what we need to know if we only paid attention; of Frank Churchill, hero or not; Jane Faifax, too good to be true and with her own mysterious ailments; the Eltons, who so deserve each other; our Dear Mr. Knightley, who upon every re-reading becomes my favorite Hero, and who on multiple readings can be seen to be quite hopelessly in Love with Emma from the start; and of course Emma, whatever we may make of her.

As we begin this bicentennial celebration of Emma, I invite you again to visit Sarah Emsley’s blog on “Emma in the Snow” where there will be bi-weekly posts starting December 23rd through March 2016. Sarah has garnered an impressive group of Austen folk to participate – so-re-read your Emma and be prepared to spend these next few months immersing yourself in this novel where nothing much seems to happen, but of course everything about human nature does. I end here with this thoughtful quote from the Cambridge edition – think on this as you begin your re-reading adventure:

This is a novel that does not ask its readers either to like or dislike its heroine: it invites them to question their responses, and to recognize their capacity to elevate their likings and dislikings to the status of moral judgements. (Introd. Emma, xxxviii)

*********

Some favorite illustrations of the proposal scene:

CE Brock, Emma (Dent, 1898) – Mollands

Hugh Thomson, Emma (Macmillan, 1896) – British Library

*************

References:

Austen, Jane. Emma: An Annotated Edition. Ed. Bharat Tandon. Harvard UP, 2012.

_____. Emma: The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen. Ed. Richard Cronin and Dorothy McMillan. Cambridge UP, 2005, p bed. 2013.

_____. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 4th ed. Oxford UP, 2011.

_____. The Works of Jane Austen: Minor Works. Ed. R. W. Chapman. Oxford UP, 1988 edition, c1954.

Austen-Leigh, James Edward. A Memoir of Jane Austen. Folio Society, 1989 (based on 1871 edition).

Fergus, Jan. Jane Austen: A Literary Life. Macmillan, 1991. See also Sabor, 1-16.

Gilson, David. A Bibliography of Jane Austen. Oak Knoll Press, 1997.

Sabor, Peter, ed. Cambridge Companion to Emma. Cambridge UP, 2015.

Upcoming posts on Emma: Stay tuned!

- The Backstory of publishing Emma

- Emma’s Christmas Eve

- Emma‘s illustrators

c2015 Jane Austen in Vermont

A pristine 1st of Emma for sale last year for £100,000

A pristine 1st of Emma for sale last year for £100,000