Pride and Prejudice

Guest Post: Philip Gough, Jane Austen Illustrator ~ by Hazel Mills

Gentle Readers: I welcome today, Hazel Mills, who has most generously written a post about one of Austen’s many illustrators, Philip Gough. I had written two posts on Gough [see below for links] but little was known about him personally. Hazel has done some extensive research into his life and works, and she shares this most interesting information with us here. Thank you Hazel!

***************

Philip Henry Cecil Gough

by Hazel Mills

The artist, Philip Henry Cecil Gough, was born on the 11th June 1908 in Warrington, Lancashire, England, the eldest of four children. He was born to Cyril Philip Gough and Winifred Mary Hutchings.

Philip was from a long line of leather tanners, curriers and bark factors, the latter using bark to soften leather. His family were wealthy owners of tanneries with evidence of his father travelling abroad to the USA in 1925 on business.

Philip’s paternal grandfather, also a Philip, had carried on the family business in Wem, Cheshire with two of his three brothers. It obviously provided a good income as all four brothers had been to private boarding schools. In 1880, the tannery company of grandfather, Philip, and his brother was dissolved and Philip continued alone.[1]

It is Philip’s maternal side that gives us the clue to his artistic side. His mother Winifred, also born into a family of tanners, travelled to Brussels to study Art and Music before her marriage. She also played the viola in various orchestras. [2]

Before 1914 the Gough family moved to Moore, near Runcorn in Cheshire [3] and then in 1921, at the age of 12, Philip was sent to Loretto School, just outside Edinburgh, Scotland, as a boarder.[4] On the 4th and 5th April of that year Philip assisted in the painting of the scenery in the staging of “Much Ado About Nothing” [5] in the gymnasium of the school. The art master he assisted was Colonel Buchanan-Dunlop, who, during the famous ceasefire at Christmas 1914, led the singing of the carols from a sheet sent to him from Loretto School. [6]

Again in 1924, Philip painted scenery for the school production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, which was performed in aid of the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, again assisting Col. Buchanan-Dunlop. [7]

Philip left school in 1925. [8] It is known that he attended art school in Cornwall and Liverpool. He entered Liverpool College of Art in February 1926 and a year later, while still at the college, designed the scenery for the pantomime, “Robinson Crusoe”, at the Garrick Theatre in London. In 1928, after leaving the Liverpool College of Art, he designed about 60 costumes for “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” for the Liverpool Playhouse with a photo being published in the “Graphic newspaper” on 19th January 1929 [9] It is also thought that he designed shop windows around this time.

1929 saw Philip working on a prestigious new project. He was responsible for all the scenery and costumes for A.A. Milne’s new play, “Toad of Toad Hall” at the Liverpool Playhouse, based on Kenneth Grahame’s book, “Wind in the Willows”. “The Stage” described Philip’s work as “both novel and extremely beautiful”. [10] At this time, Philip was still only twenty one years old. A.A. Milne also wrote a play of “Pride and Prejudice” called “Miss Elizabeth Bennet”. This was also produced at the Liverpool Playhouse. But sadly it was not Philip that did the scenery for this one, but a Charles Thomas. [11]

In September of the following year, Philip designed scenery and costumes for “Charlots’s Masquerade”, a variety show at the Cambridge Theatre in London. There is even some Pathé News footage of this in existence. [you can view it here:

****************

It must be around this time that Philip meets his first wife, Mary O’Gorman, as the London Electoral register of 1930 shows him living in what appears to be a lodging house at the same address as her. It’s not know if they were actually living together as the listing is just alphabetical. Over the next eight years Gough is involved in costume and set design for at least seven productions, the first two at the Liverpool Playhouse but the following ones were all in various locations in London.

Towards the end of this time the first book illustrated by Gough that I could find was the wonderfully named*, For Your Convenience: a learned dialogue instructive to all Londoners & London visitors, overheard in the Thélème Club and taken down verbatim by Paul Fry, [pseudonym for Thomas Burke] and published by Routledge in 1937.

[* this book is republished today as For Your Convenience: A Classic 1930’s Guide to London Loos – in 1937 it was a heavily disguised guide to London toilets for homosexual encounters.]

***********

In 1939 Philip married Mary Catherine O’Gorman in Chelsea. The 1939 England and Wales register shows the married couple living in elegant Walpole Street, Chelsea. The house is again the home of what appears to be boarders. Philip is described as working as an artist and designer of theatrical scenery, Mary is a secondary school teacher.

The following year Philip worked on “The Country Wife” at the Little Theatre, Haymarket, London and The Illustrated London News reported that the “décor by Mr. Philip Gough is the chief charm of this production.” [12]

The next few years, over the time of the Second World War, seem to be a very quiet time for Philip. I can only find his illustration of a book by Eleanor Farjeon called The New Book of Days, an anthology of rhymes, proverbial tales, traditions, short essays, biographical sketches and miscellaneous information, one piece for each day of the year. In 1936, Philip had also designed the sets and costumes for a play by Eleanor and Hubert Farjeon, called “The Two Bouquets”.

Philip’s father died in 1946 when Philip was still living in Chelsea. In 1948 he appears to have left his wife and is now living at another address in Chelsea with a Joan Sinclair.

1947 was a prolific year as a book illustrator, with four books for Peter Lunn publishers including “Fairy Tales” by Hans Christian Andersen. The following year would be his foray into Jane Austen Novels with the 1948 publication of Emma, published by MacDonald for their Illustrated Classics series.

I have tracked down forty-two books between 1937 and 1973 where he drew illustrations throughout, but in addition Philip designed many, many more dust jackets for novels such as those of Georgette Heyer:

and non fiction tiles such as 1960s reprints of the four volume “A History of Everyday Things in England” that first appeared in 1918:

Philip also did a few more set designs in the 1950s but more of his time was spent illustrating books including Pride and Prejudice (1951), Mansfield Park (1957) and Sense and Sensibility (1958) for Macdonald. You can see many of the illustrations here:

and here:

*****************

In Philip’s personal life, tragedy hit when his mother was killed in an accident when she was hit by an army truck in 1952. Philip married Joan in 1953 which is the last year in which I can find any more set and costume designing.

1961 saw the Macdonald publication of both Northanger Abbey and Persuasion with his illustrations and he continued to illustrate books until at least 1973.

Philip Gough died in London on 24th February 1986, leaving a fortune of £42,661.

Philip’s sisters also deserve a mention. Sheila May Gough was qualified as a nurse and during WWII joined the ‘Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service’. She served in Europe before being posted to Malta. In 1943 Malta became the base for the invasion of Sicily. It was codenamed ‘Operation Husky’ and began on the night of 9 July and lasted for six weeks. Sheila was awarded the ‘Associate of the Royal Red Cross’ for “special devotion to duty…and complete disregard for her own safety”. [13] Sheila remained unmarried until the age of 58, in 1975, when she married Donald Verner Taylor C.B.E. who had been in the Army Dental Corps in Malta at the same time as her.

Less is known of his sister Gwendoline Winifred other than she was a school teacher at a boarding school in Nottingham in 1939 [14] but in 1941 sailed to South Africa where she stayed until 1946. [15] More is known of Brenda Irene, or rather Flight Officer Brenda Irene Gough. The 1939 register records that Brenda was working as a secretary for the Civil Nursing Reserve and living in Wimbledon. She joined the WAAF (The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force) after May 1941 . In 1943, Brenda was promoted to Section Officer in the Administrative and Special Services Branch and later promoted to Flying Officer. During the war women were paid two thirds of the salary of their male counterparts.

Philip Gough has left an enormous body of work and original works of his illustrations can achieve high prices today, for example, a signed original gouache artwork for the dust wrapper to Georgette Heyer’s The Foundling currently commands a price of around $2,500.

**********************

Footnotes:

- The London gazette May 27 1881

- Obituary Cheshire Observer Dec 01 1951

- Kelly’s Directory 1914

- https://archives.loretto.com/archive/the-lorettonian/1921-vol-44/777604-1921-vol-44-0031jpg?q=gough

- https://archives.loretto.com/archive/the-lorettonian/1923-vol-46/777827-1923-vol-46-0026jpg?q=gough

- https://www.loretto.com/christmas-truce-commemoration/47361.html

- https://archives.loretto.com/archive/the-lorettonian/1924-vol-47/777740?q=gough

- https://archives.loretto.com/archive/the-lorettonian/1925-vol-48/777849?q=gough

- The Graphic – Saturday 19 January 1929

- The Stage – Thursday 26 December 1929

- The Era – Wednesday 9 September 1936

- Illustrated London News – Saturday 20 April 1940

- National Archives

- 1939 England and Wales Register

- UK incoming and Outgoing passenger lists

Image acknowledgements:

- Liverpool College of Art Record -Liverpool College of Art Archives

- Mid summer Night’s Dream Image courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library (c) Illustrated London News/Mary Evans Picture Library.

- For Your Convenience images – Care of Daniel Crouch Rare Books – crouchrarebooks.com

________________________________

Author bio:

Hazel Mills is a retired science teacher and a founder member and Chair of the Cambridge Group of the UK Jane Austen Society. Until her move to Denmark, she was a Regional Speaker for the Society. Hazel discovered Austen as a thirteen year old Dorset schoolgirl when reading Pride and Prejudice and fell in love for the first time with Mr Darcy. She has researched the history of Jane Austen’s time, presenting illustrated talks, around England and Scotland, on diverse subjects including: Travel and Carriages in Jane Austen’s time; the Life of John Rawstorn Papillon, Rector of Chawton; Food production and Dining; Amateur Theatricals at Steventon, and the Illustrators of Austen’s novels. She lives in a lovely house overlooking the sea with her husband who built her a library to house her extensive Austen collection, which includes over 230 different copies of Pride and Prejudice.

***************

Do you have a favorite Philip Gough illustration?? Please leave a comment below.

©2022, Jane Austen in Vermont and Hazel Mills

Collecting Jane Austen: ‘The Accomplished Lady’ by Noël Riley

“It is amazing to me,” said Bingley, “how young ladies can have patience to be so very accomplished as they all are.”

“All young ladies accomplished! My dear Charles, what do you mean?”

“Yes, all of them, I think. They all paint tables, cover screens, and net purses. I scarcely know any one who cannot do all this, and I am sure I never heard a young lady spoken of for the first time, without being informed that she was very accomplished.”

“Your list of the common extent of accomplishments,” said Darcy, “has too much truth. The word is applied to many a woman who deserves it no otherwise than by netting a purse or covering a screen. But I am very far from agreeing with you in your estimation of ladies in general. I cannot boast of knowing more than half a dozen, in the whole range of my acquaintance, that are really accomplished.”

“Nor I, I am sure,” said Miss Bingley.

“Then,” observed Elizabeth, “you must comprehend a great deal in your idea of an accomplished woman.”

“Yes, I do comprehend a great deal in it.”

“Oh! certainly,” cried his faithful assistant, “no one can be really esteemed accomplished who does not greatly surpass what is usually met with. A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word; and besides all this, she must possess a certain something in her air and manner of walking, the tone of her voice, her address and expressions, or the word will be but half deserved.”

“All this she must possess,” added Darcy, “and to all this she must yet add something more substantial, in the improvement of her mind by extensive reading.”

“I am no longer surprised at your knowing only six accomplished women. I rather wonder now at your knowing any.”

“Are you so severe upon your own sex as to doubt the possibility of all this?”

“I never saw such a woman. I never saw such capacity, and taste, and application, and elegance, as you describe united.”

[Pride & Prejudice, Vol. 1, Ch. 8]

*********************

And so, to truly understand what Mr. Darcy is driving at, to understand anything about Jane Austen’s world, you need to study this quite formidable lady, if indeed such a one existed! – and there is no better book on the subject than Noël Riley’s The Accomplished Lady: A History of Genteel Pursuits c.1660-1860 (Oblong, 2017).

“This is a study of the skills and pastimes of upper-class women and the works they produced during a 200-year period. These activities included watercolours, printmaking and embroidery, shell work, rolled and cut paper work, sand painting, wax flower modelling, painting on fabrics and china, leather work, japanning, silhouettes, photography and many other activities, some familiar and others little known.

The context for these activities sets the scene: the general position of women in society and the constraints on their lives, their virtues and values, marriage, domestic life and education. This background is amplified with chapters on other aspects of women’s experience, such as sport, reading, music, dancing and card-playing.” [from the book jacket].

Table of Contents:

Introduction

1. A Woman’s Lot

2. Educating a Lady

3. Reading and Literary Pursuits [my favorite chapter]

4. Cards, Indoor Games and Theatricals

5. The Sporting Lady

6. Dancing and Public Entertainment

7. Music

8. Embroidery

9. Threads and Ribbons

10. Beadwork

11. Shellwork

12. Nature into Art

13. Paperwork

14. Drawing and Painting

15. Creativity with Paints and Prints

16. Japanning

17. Penwork

18. Silhouettes

19. Photography and the Victorian Lady

20. Sculpture, Carving, Turning and Metalwork

21. Toys and Trifles.

Includes extensive notes, an invaluable bibliography of primary and secondary sources, and an index.

I have mentioned before that in collecting Jane Austen, you will often go off into necessary tangents to learn about her Life and Times – this can take you in any number of directions, but understanding the Domestic Arts of the Regency period is an absolute must – and there are MANY books on the subject, cookery alone could fill shelves. But here in this one book we find a lavishly illustrated, impeccably researched study of all the possible activities a lady of leisure [no cookery for My Lady] can get herself caught up in….whether she becomes accomplished or not is beyond our knowing, but certainly Mr. Darcy would find at least ONE lady in these pages who might meet his strict requirements, despite Elizabeth’s doubting rant.

The Georgian Society of East Yorkshire offers a nice review here with a sample page: http://www.gsey.org.uk/post/992/book-review-the-accomplished-lady-a-history-of-genteel-pursuits-c-16601860-by-nol-riley

It is always a worthwhile effort to check the index of every book you pick up to see if Jane Austen gets a mention. And here we are not disappointed – Austen shows up on many pages, and five of her six novels are cited in the bibliography – all but Persuasion for some odd reason – one would think Anne Elliot’s skills at the pianoforte would have merited a mention?

This image of page 165 quotes Austen about patchwork when she writes to Cassandra on 31 May 1811:“Have you remembered to collect peices for the Patchwork?”

So, let’s stop to think about the varied accomplishments of Austen’s many female characters…anyone want to comment and give a shout out to your own favorite and her accomplishments / or lack thereof? Is anyone up to Mr. Darcy’s standards?

©2021 Jane Austen in Vermont

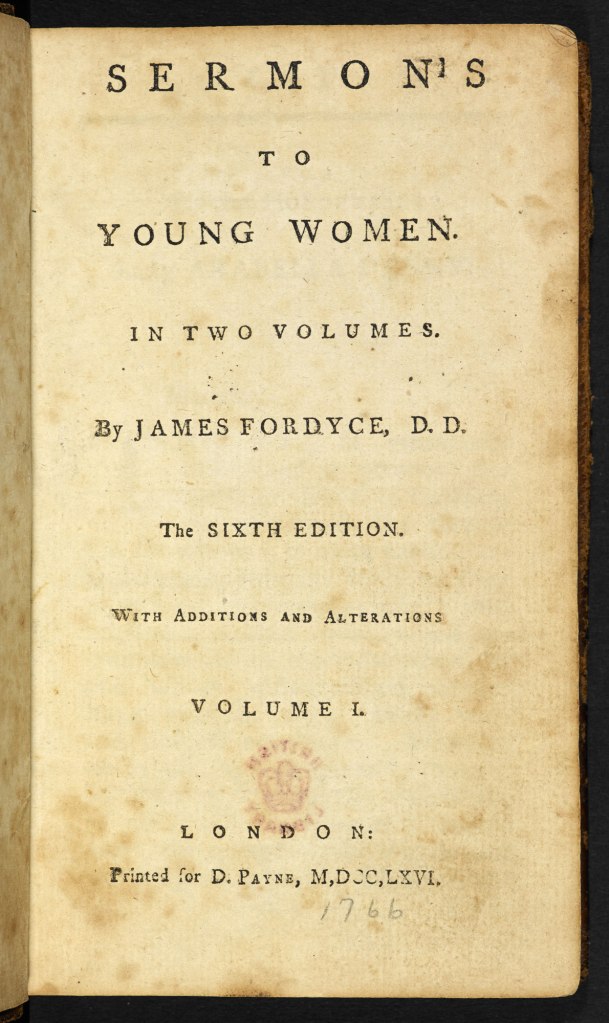

Collecting Jane Austen ~ ‘Sermons to Young Women’ by James Fordyce

I shall take a little side road today with this discussion of must-haves in your Jane Austen collection – here an example of a book Jane Austen had read, referred to, satirized, and which then became the most interesting thing about Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice.

Part of collecting Jane Austen is to learn about and possibly add to your collection those books known to have been read by her, a fascinating list compiled from the many allusions in her novels and her letters. You can start with R. W. Chapman’s “Index of Literary Allusions, which you can find online.

Chapman’s list first appeared in the NA and P volume of the Oxford edition we looked at last week – more has been added to this – but this is a good start – you could spend the rest of your life just collecting “allusion” books and you will completely forget what you were collecting in the first place.

But Fordyce is one you must have, should read, for if nothing else it will give you a better idea of where Mr. Collins is coming from and what Austen has to say about both he AND Fordyce.

Sermons to Young Women, by Dr. James Fordyce, is certainly one the most well-known of all the various conduct manuals Austen would have had access to, published in London in 1766, “and by 1814, the year after Pride and Prejudice appeared, it had gone though 14 editions published in London alone.” [Ford, intro, i].

We all recall that in Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Collins chooses to read Fordyce’s Sermons aloud to the Bennet sisters, Lydia especially unimpressed:

By tea-time, however, the dose had been enough, and Mr. Bennet was glad to take his guest into the drawing-room again, and, when tea was over, glad to invite him to read aloud to the ladies. Mr. Collins readily assented, and a book was produced; but, on beholding it (for everything announced it to be from a circulating library), he started back, and begging pardon, protested that he never read novels. Kitty stared at him, and Lydia exclaimed. Other books were produced, and after some deliberation he chose Fordyce’s Sermons. Lydia gaped as he opened the volume, and before he had, with very monotonous solemnity, read three pages, she interrupted him with:

“Do you know, mama, that my uncle Philips talks of turning away Richard; and if he does, Colonel Forster will hire him. My aunt told me so herself on Saturday. I shall walk to Meryton to-morrow to hear more about it, and to ask when Mr. Denny comes back from town.”

Lydia was bid by her two eldest sisters to hold her tongue; but Mr. Collins, much offended, laid aside his book, and said:

“I have often observed how little young ladies are interested by books of a serious stamp, though written solely for their benefit. It amazes me, I confess; for, certainly, there can be nothing so advantageous to them as instruction. But I will no longer importune my young cousin.” [P&P, Ch. XIV]

Collins, done with such young and frivolous young ladies, heads off for a game of backgammon with Mr. Bennet…

Illustrators of Pride and Prejudice have turned this scene into a visual treat:

Hugh Thomson, P&P (George Allen, 1894)

Chris Hammond, P&P, Gresham, 1900

**************

Fordyce (1720-1796) was a Scottish Presbyterian minister and a poet, but is most known for his Sermons. He also published Addresses to Young Men in 1777. But would we even be talking about him today if it weren’t for Jane Austen??!

As for his poetry, this is the only poem to be found on the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive, attesting to Fordyce’s seeming obsession with Female Virtue…

TRUE BEAUTY

The diamond’s and the ruby’s blaze

Disputes the palm with Beauty’s queen:

Not Beauty’s queen commands such praise,

Devoid of virtue if she’s seen.

But the soft tear in Pity’s eye

Outshines the diamond’s brightest beams;

But the sweet blush of Modesty

More beauteous than the ruby seems.

****************

Further Reading:

- For more information you can read this essay on Fordyce and P&P by Susan Allen Ford in Persuasions On-Line “Mr. Collins Interrupted: Reading Fordyce’s Sermons with Pride and Prejudice“ [POL 34.1 (2013)].

- Here are some images and commentary at the British Library: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/sermons-to-young-women

- Here’s the full text of a 2-volumes-in-one American edition from 1809 [the 3rd American from the 12th London edition] at HathiTrust: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015008247788&view=1up&seq=5

- If your main concern is with “Female Virtue,” the University of Toronto has these two abstracts for your reading pleasure – From Sermon IV: On Female Virtue; and From Sermon V: On Female Virtue, Friendship, and Conversation: http://individual.utoronto.ca/dftaylor/Fordyce_Sermons.pdf

- As you will see in the comments below, A. Marie Sprayberry sent me this link to her excellent Persuasions On-Line essay on Fanny Price and Fordyce: “Fanny Price as Fordyce’s Ideal Woman? And Why?” http://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol35no1/sprayberry.html

Much has been written about Austen and Fordyce – the point being, you need a copy. You can find it in one of its original editions on used bookstore sites for not over the top prices – or there are many, many reprints out there.

One of the best of these is the facsimile reprint of the 10th ed. of 1786 and published by Chawton House Press in 2012. Susan Allen Ford wrote the valuable introduction and it also includes a fine bibliography. This edition is unfortunately out-of-print and I am hoping that they will republish it in the near future. It was a best-seller in its time and again today! Who knew!

©Jane Austen in Vermont

Collecting Jane Austen: Book Collecting 101

Gentle Readers: In an effort to offer weekly posts on collecting Jane Austen, I shall start with the basics of book collecting – this a general summary of things to consider with a few examples specific to Jane Austen and Pride and Prejudice in particular. This will be followed by weekly posts on randomly chosen books in the various categories I list here that I think are essential to a Jane Austen collection.

Let’s start in the pages of Pride and Prejudice in the library at Netherfield where we find Elizabeth, Miss Bingley, Mr. Bingley, and Mr. Darcy:

[Elizabeth] walked towards a table where a few books were lying. He [Bingley] immediately offered to fetch her others; all that his library afforded.

“And I wish my collection were larger for your benefit and my own credit; but I am an idle fellow, and though I have not many, I have more than I ever look into.”

Elizabeth assured him that she could suit herself perfectly with those in the room.

“I am astonished,” said Miss Bingley, “that my father should have left so small a collection of books. What a delightful library you have at Pemberley, Mr. Darcy!”

“It ought to be good,” he replied; “it has been the work of many generations.”

“And then you have added so much to it yourself, you are always buying books.” [my emphasis]

“I cannot comprehend the neglect of a family library in such days as these.”

Chatsworth Library [British Magazine]

And so, here we have the permission of Mr. Darcy himself to buy as many books as we would like!

II. The Collecting of Books:

Terry Belanger, a veteran book collector and rare book librarian once famously said “you are a collector if you have more than one copy of a single title” –

So, I ask you, how many of you have more than one copy of any of Jane Austen’s novels? And how many of you already realize that to collect all copies of books by and about Jane Austen is surely an impossible task? Even focusing on one title, say Pride and Prejudice, we would find it an impossible undertaking!

So where to start?

1. The first rule of book collecting is Collect what you Love – so I can assume that any of you reading this all love Jane Austen, and so that will be our focus… and not only the books but also the myriad objects and ephemera. You can collect anything – my son collects Sneakers, only Nike Jordans, which leads to books about sneakers, etc…!

An amusing tale about collecting one title: In a used bookshop in England a few years ago I hit the mother-load of A Child’s Garden of Verses – a title I collect –

I brought five different editions to the register, manned by a young man obviously neither the owner nor all that well-versed in the vagaries of collecting – he hesitated for a moment, looked thoughtful, and finally blurted out “Do you know that all these books are the same?” [epilogue: I bought them all…]

2. Try to find the 1st edition (and by “first edition” I mean “first printing”), and how do we do that?

1st edition Pride and Prejudice [National Library of Scotland]

For most of us, Jane Austen first editions are beyond our pocketbooks – but you will need to know the basics of book collecting to understand why some books are harder to find, and why, when you find them, they can often be expensive.

It is here you will need to decide if you want the first edition in pristine condition or if you only need a reading copy, or not even a first edition at all – this is a question to ask at every purchase.

The most difficult aspect of book collecting is how to identify a first edition – every publisher did it differently and often changed their indicators over time. There are many guides to help with this.

This Pocket Guide to the Identification of First Editions by Bill McBride is the best starting point for a general understanding of the practices of various publishers. You can also find this information online at Quill & Brush Books: https://www.qbbooks.com/first_ed_pub.php

Then you will need more specific detail on the author/subject you are collecting, and thankfully for us Jane Austen enthusiasts, David Gilson, and Keynes and Chapman before him, have largely done this work for us…

The David Gilson A Bibliography of Jane Austen will be your Bible to collecting Austen, a must-have book – I have already posted about this here: https://janeausteninvermont.blog/2021/02/26/collecting-jane-austen-gilsons-bibliography/

3. The Anatomy of a Book:

If you want to understand book terminology, you must have John Carter’s ABC for Book Collectors – the 8th edition by John Carter and Nicolas Barker. Oak Knoll Press / British Library, 2004.

It is now available online at ILAB: https://ilab.org/sites/default/files/2018-01/ABC-BOOK-FOR-COLLECTORS_0.PDF

Another easily accessible glossary is on Abebooks: https://www.abebooks.com/books/rarebooks/collecting-guide/understanding-rare-books/glossary.shtml

Most commonly used terms:

- 1st edition

- Issue

- Points

- Boards

- Spine head, spine tail

- Backstrip

- Text block

- Hinge

- Joint

- Endpapers

- Half-title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Frontispiece

- Publisher’s cloth

- Catchword: “heard” at the bottom of the page is the catchword = the first word on the next page

-Vignette

-Foxing:

Example of foxing: Dent 1908 reprint, illus. HM Brock

- Leather bindings: ¼, ¾, etc…

- Size terms: folio, quarto (4to), octavo (8vo), duodecimo (12mo), 16mo, etc

https://www.abebooks.com/books/rarebooks/collecting-guide/understanding-rare-books/guide-book-formats.shtml

4. Determining value: supply and demand – Desirability+Scarcity=Value

- Is the book still in print?

- How many copies were printed?

- Is this the author’s first book? – Sense and Sensibility is the most valuable

- How did the book first appear? – binding, dust jacket? [value greatly reduced if lacking jacket: 75% – fiction, 20% – non-fiction]. Eg. S&S first published in boards is more valuable than the finest leather binding

S&S 1st ed in boards and leather bound]: estimated value: $200,000 / $50,000.

- Illustrations present? are they all there?

- Condition, Condition, Condition! – most important factor! [see more below]

- Where do you find values? There are many guides to consult:

- Allen and Patricia Ahearn. Collected Books: A Guide to Identification and Values. 4th ed. (2011); see also their author guides – one on JA from 2007

- American Book Prices Current: auction sales, so actual value

- Bookseller catalogues: what titles are selling for

- Author and subject bibliographies

- Internet: bookselling sites: be wary – prices all over the place

5. CONDITION is the most important issue: prices will vary depending upon condition – even if you have the 1st edition – if it is in deplorable condition that will affect the value.

Booksellers grade a book’s condition using the terms below, from “As New” down to “Poor”: for instance VG [for the book ] / VG [for the jacket] – anything less than a VG is really not collectible:

VERY FINE/NEW [VF / NEW]: As new, unread.

FINE: Close to new, showing slight signs of age but without any defects.

VERY GOOD [VG]: A used book that shows some sign of wear but still has no defects.

GOOD [G]: A book that shows normal wear and aging, still complete and with no major defects.

FAIR: A worn and used copy, probably with cover tears and other defects.

POOR: a mess really, but might have some redeeming qualities

READING COPY: any book less than VG

*************

An interesting tale to demonstrate this: The rare bookseller Stuart Bennett [no relation to our esteemed Bennet family!] writes in his book Trade Bookbinding in the British Isles 1660-1800.

Alas! pre-Austen, but we find her in a NOTE: [an aside – always check indexes for Jane Austen – you will be pleasantly surprised to see how often she turns up and in the most amazing places!]

Bennett writes in a footnote on the issue of publishing in boards vs. the wealthy having their favorite books bound in leather:

What is certain is that wrappered and boarded popular literature was not part of the visual landscape of country house libraries. In my experience these books, when kept, found their way into cupboards underneath the display bookcases, or into passages or rooms used by servants. In my days at Christie’s I once spent hours in the pantry cupboards of a Scottish country house, searching through stacks of these wrappered and boarded books among which I found, virtually as new, Volume III of the first edition of Sense and Sensibility. When I found the other two volumes I remarked to the aristocratic owners that this was one of the most valuable books in the house, as exceptional survival in original condition, and doubtless so because one of their ancestors had bought Jane Austen’s first novel, read it, and hadn’t cared enough to send it to for rebinding, and never bought another. My ebullience was arrested by an icy stare from the Countess, who replied, “I am sure, Mr. Bennett, that our ancestors would never have felt that way about Jane Austen.” [3]

Stuart tells me: this S&S set the then-record auction price in 1977 or 1978 (he was the auctioneer!), and turned up about twenty or maybe 25 years later offered by a London bookseller for, as he recalls, $200,000. Then it disappeared again.

Question: Should you buy a less collectible book because you cannot afford the higher price? – do you just want a reading copy or need to fill a gap in your collection? – you can decide this on a case-by-case basis – what becomes available and when and how much you can spend…

6. Where to find Books:

“Beauty in Search of Knowledge” – Thomas Rowlandson

– Local bookstores: sadly less of them, but still the best resource of Jane Austen books – a bookseller who will know your likes, will buy with you in mind, someone to trust…

– Specific booksellers: those who specialize in Jane Austen and other women writers – shops, catalogues – you can find at book-fairs, being on their catalogue mailing list, and on the internet. For eg. Jane Austen Books https://www.janeaustenbooks.net/

– Auctions / auction catalogues

– The Internet: major used bookselling sites: you need to be an informed consumer!

- Abebooks [part of amazon, but separate]: www.abebooks.com

- Alibris: www.alibris.com

- Biblio: www.biblio.com

- ILAB: www.ilab.org/index.php

- Amazon: www.amazon.com

- Barnes & Noble: www.barnesandnoble.com/

- Ebay: www.ebay.com/chp/books

- Etsy: www.etsy.com/

- Book searching sites: [searches all used book databases]

- – viaLibri http://www.vialibri.net/index.php?pg=home

- – Bookfinder http://www.bookfinder.com/

- – AddALL: http://www.addall.com/

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of the Internet: I could write a very lengthy post just on this – so I will only emphasize the biggest positive – you have at your fingertips a Global marketplace – no longer dependent on a brick & mortar shop around the corner [sad as this is to me!]

Biggest negative: be in be-wary mode – who are you buying from? – how to decide which is the best copy with so many price and condition discrepancies? – my best advice? – choose a bookseller who knows what they are about: valid and complete descriptions and a price that seems reasonable in light of other copies on offer.

A word about EBAY: a Gigantic auction house always open! – an amazing resource but also the biggest potential for getting a bad deal – you need to be an informed consumer!

Best use of the internet: Want Lists – most book sites do this and auction houses offer “alerts” – you will be notified when an item becomes available…

7. Caring for your collection: lots of information here to consider…just not today.

II. What to Collect:

Now comes the hard part – with so much out there on Jane Austen, where do you even begin? The need to focus on one particular aspect [say just collecting copies of Pride and Prejudice], or by zeroing in on a certain illustrator you like [the Brock brothers], or only books with fine decorative bindings [so many] – this list covers the gamut of possibilities – you just need to choose what you are most interested in. You must however start with a core collection:

A. A Jane Austen Core Collection

1. The Works: the Oxford edition, ed. by Chapman (1923); the Cambridge edition, general editor Janet Todd, with each volume edited by a a different scholar; a set of reading copies of each novel – ones you can markup, underline, and make notes

2. The Letters – all editions [Brabourne, Chapman, Le Faye, Modert]

3. R. W. Chapman’s books on Jane Austen

4. Biography: the Memoir and everything since!

5. A Chronology of Jane Austen, Deirdre Le Faye (Cambridge, 2006)

6. The Bibliographies: Keynes, Chapman, Gilson, Barry Roth’s 3 volumes, and those continued annually in Persuasions; the Cambridge Bibliographies, etc…

7. Brian Southam. The Critical Heritage. Vol I. 1811-1870. Routledge, 1979; The Critical Heritage, Vol. II. 1870-1940. Routledge, 1987. – now available as digital reprints, 2009

8. Critical works: starting off point to further study – where to start?? The bibliographies; “Companions” – “Handbooks” – “Casebooks”

9. The World of Jane Austen: [endless material!]

- The Arts: Music, Art, Architecture; Interior Design and Decorative Arts; Landscape

- Georgian and Regency History: Political, Economic, Social, Religious

- Social life and customs: Etiquette; Gender / Class issues; Dancing; Costume and Fashion

- Domestic Arts: Cookery, Needlework, Women’s work, Family life, Home-life, Servants

- Medical History

- Military History: the Royal Navy, the Militia, The French Revolution, the American Revolution, Napoleonic Wars, War of 1812

- Geographical History and Maps

- Travel and Transportation: Carriages, Roads, Guidebooks, etc…

- Literary Theory, History of the Novel, Narrative Theory, Language

B. Collecting a specific Jane Austen novel: as an example Pride & Prejudice

- 1st editions

- American editions

- Specific Publishers: Bentley, Macmillan, Dent, Oxford, Folio Society, LLC, Penguin, etc.

- Translated editions

- Illustrators: also single illustrations

- Decorative bindings / cover art – to include paperbacks

- Critical editions: with scholarly editing and introductions

- Books where P&P shows up

- Association copies: e.g. Sarah Harriet Burney’s copy

- Books that influenced Austen: e.g. Frances Burney’s Cecilia

- Adaptations: Editions for young readers; Dramatizations; Films, Audiobooks

- Sequels! – endless potential!

- History / Social Life and Customs of the times, specific to P&P – fill your bookshelves!

- Ephemera and Physical Objects – P&P merchandise in popular culture, many to do with Colin Firth…(!)

*****************

Ok, now you know everything to know about Book Collecting – you can begin this lifelong fun-filled endeavor! Join me next week for the first of many [I hope] Jane Austen-related titles you must have on your shelves…all with Mr. Darcy’s approval. Any questions or suggestions, please comment.

©2021, Jane Austen in Vermont

Mary Bennet’s Reading in “The Other Bennet Sister” by Janice Hadlow

In Janice Hadlow’s The Other Bennet Sister, a brilliant effort to give the neglected-by-everyone Mary Bennet a life of her own, Mary’s reading is one of the most important aspects of the book – we see her at first believing, because she knows she is different than her other four far prettier and more appealing sisters, that her prospects for the expected life of a well-married woman are very limited, and that she must learn to squash her passions and live a rational life. She also mistakenly thinks that by becoming a reader of philosophical, religious, and conduct texts that she will finally gain approval and maybe even love from her distant, book-obsessed father.

In Janice Hadlow’s The Other Bennet Sister, a brilliant effort to give the neglected-by-everyone Mary Bennet a life of her own, Mary’s reading is one of the most important aspects of the book – we see her at first believing, because she knows she is different than her other four far prettier and more appealing sisters, that her prospects for the expected life of a well-married woman are very limited, and that she must learn to squash her passions and live a rational life. She also mistakenly thinks that by becoming a reader of philosophical, religious, and conduct texts that she will finally gain approval and maybe even love from her distant, book-obsessed father.

So Mary embarks on a course of serious rational study – and one of the most insightful things in the book is that she learns, after much pain, that this is no way to lead a life, to find happiness, to find herself. She rejects the novels like the ones Mrs. Bennet finds at the local circulating library as being frivolous, largely because James Fordyce tells her so…

So, I have made a list of all the titles that Hadlow has Mary reading or referring to – all real books of the time, and many mentioned and known by Jane Austen. Hadlow is very specific in what books she puts in Mary’s hands! And shows her own knowledge of the reading and the reading practices of Austen’s time. [If anyone detects anything missing from this list, please let me know…]

I am giving the original dates of publication of each title; most all the titles in one edition or another are available on Google Books, HathiTrust, Internet Archive, or the like – I provide a few of those links, if you are so inclined to become such a rational reader as Mary….

***************

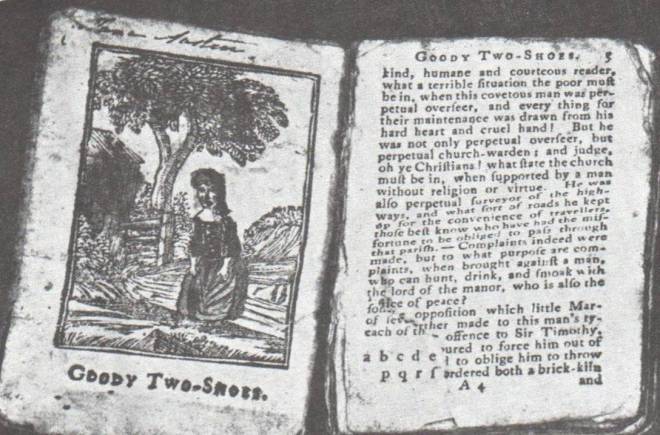

Anonymous. The History of Little Goody Two Shoes (show JA’s copy). London: John Newbury, 1765. Attributed to various authors, including Oliver Goldsmith. We know that Jane Austen has her own copy of this book, here with her name on it as solid proof.

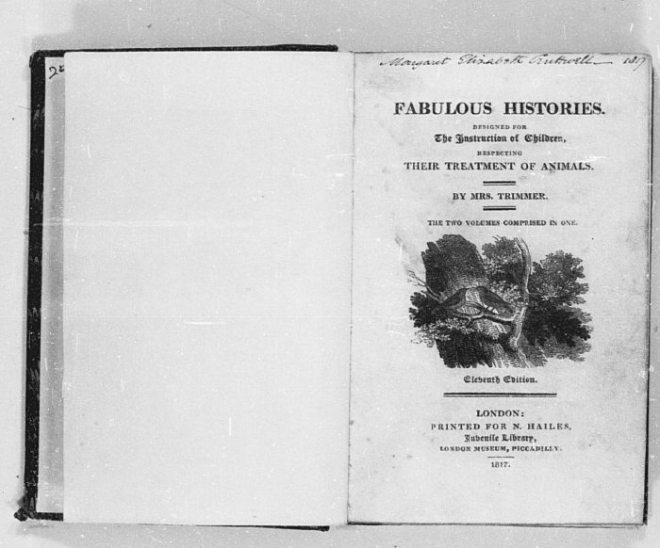

Mrs. [Sarah] Trimmer. The Story of the Robins. Originally published in 1786 as Fabulous Histories, and the title Trimmer always used. You can read the whole book here: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Story_of_the_Robins

image: HockliffeProject: http://hockliffe.dmu.ac.uk/items/0241pages.html?page=001

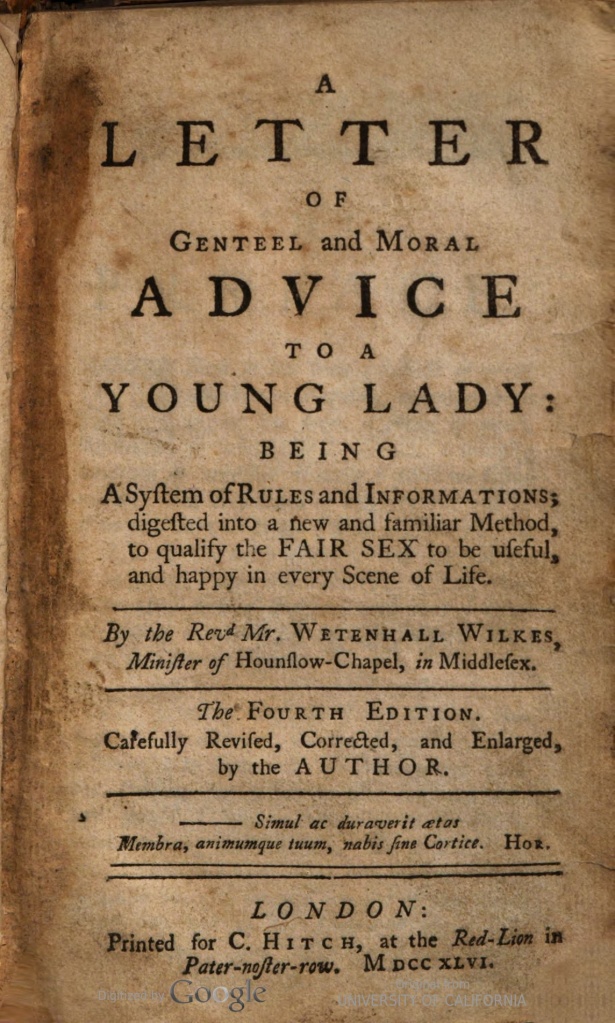

Rev. Wetenhall Wilkes. A Letter of Genteel and Moral Advice to a Young Lady: Being a System of Rules and Informations: Digested Into a New and Familiar Method, to Qualify the Fair Sex to be Useful, and Happy in Every Scene of Life. London, 1746. Another conduct book.

Full text here: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012393127

***********

Catharine Macaulay. The History of England. 8 vols. London, 1763-83. A political history of the seventeenth century, covering the years 1603-1689. This was very popular and is in no way related to the later History published by Thomas Babington Macaulay. You can read more about this influential female historian in this essay by Devoney Looser: Catharine Macaulay: The ‘Female Historian’ in Context

image: British Library https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/sermons-to-young-women

Rev. James Fordyce. Sermons to Young Women. London, 1766. A conduct manual.

In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Collins chooses to read Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women aloud to the Bennet sisters, Lydia especially unimpressed: “Lydia gaped as he opened the volume, and before he had, with very monotonous solemnity, read three pages, she interrupted him …’.

You can find it on google in later editions, but here is an abstract for 2 of the sermons to give you an idea.

And here an essay on Fordyce and P&P by Susan Allen Ford, who also wrote the introduction for the Chawton House Press edition of the Sermons (2012) : http://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol34no1/ford.html

*************

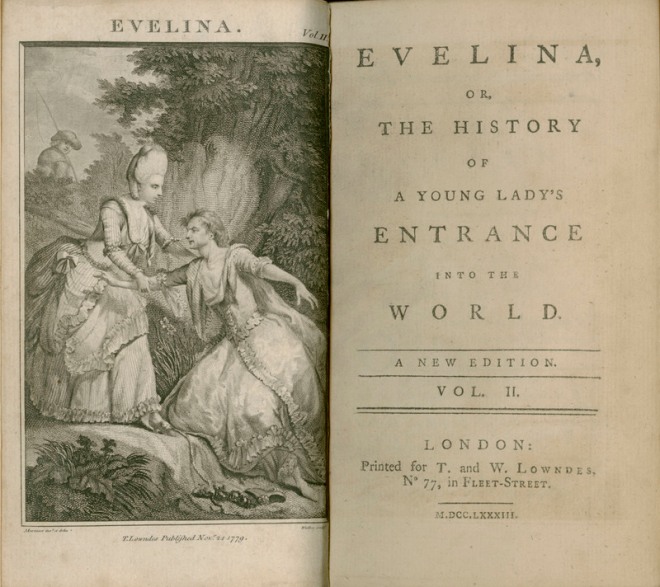

Frances Burney. Evelina, or the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World. London, 1778. Hadlow gives Evelina a good hearing – in the discussion in Mr. Bennet’s library with Elizabeth and Mary. Elizabeth directly quotes Austen’s own words in defense of the novel that are found in Northanger Abbey. [Evelina, and Mary’s difficulty in coming to terms with such a frivolous story, is mentioned more than once].

***********

Other Novels mentioned are:

– Samuel Richardson. The History of Sir Charles Grandison. London, 1753. 7 vols. Reported to be Austen’s favorite book, all seven volumes!

– Henry Fielding. The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. 4 vols. London, 1749. Supposedly the reason Richardson wrote his Grandison. [Mentioned more than once] – I think we should read this book next for our JABC!

– Laurence Sterne. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. 9 vols. London, 1759-1767.

***************

Hugh Blair. Sermons. Vol. 1 of 5 published in 1777.

You can view it full-text at HathiTrust.

Mary Crawford refers to Blair in Mansfield Park:

“You assign greater consequence to the clergyman than one has been used to hear given, or than I can quite comprehend. One does not see much of this influence and importance in society, and how can it be acquired where they are so seldom seen themselves? How can two sermons a week, even supposing them worth hearing, supposing the preacher to have the sense to prefer Blair’s to his own, do all that you speak of? govern the conduct and fashion the manners of a large congregation for the rest of the week? One scarcely sees a clergyman out of his pulpit.”

***************

William Paley. A View of the Evidences of Christianity. London, 1794.

Aristotle. The Ethics of Aristotle. [no way to know the exact edition that Mr. Collins gives to Mary – it’s been around for a long time!]

Mentions: all Enlightenment thinkers and heavy reading for Mary!

– John Locke

– William Paley (again)

– Jean-Jacques Rousseau

– David Hume

A Dictionary of the Greek Language – Mr. Collins gives a copy to Mary.

*************

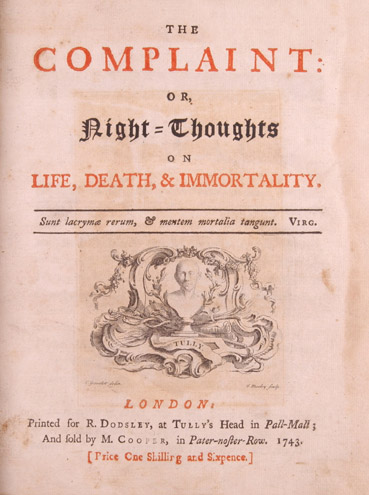

Edward Young. The Complaint: or, Night-Thoughts on Life, Death, and Immortality. [Known as Night-Thoughts]. London, 1742-45. [No wonder Mr. Hayward suggested a lighter type of poetry!]

You can read the whole of it here, if you are up to it…: https://www.eighteenthcenturypoetry.org/authors/pers00267.shtml

**************

William Wordsworth, portrait by Henry Edridge, 1804; in Dove Cottage, Grasmere, England. Britannica.com

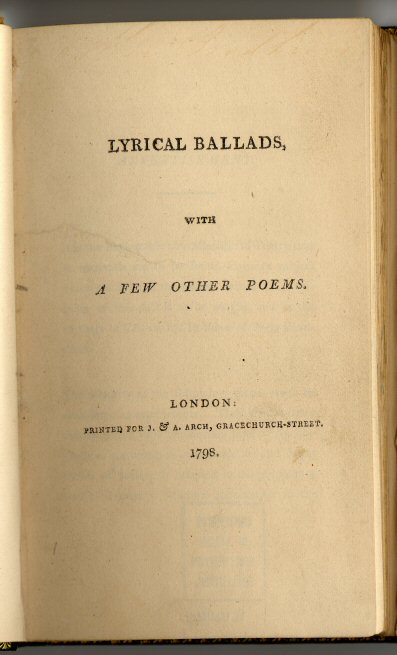

William Wordsworth. Lyrical Ballads. London, 1798. Full title: Lyrical Ballads, with a Few Other Poems is a collection of poems by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge [Mr. Hayward does not mention Coleridge at all!], first published in 1798 and considered to have marked the beginning of the English Romantic movement in literature. Most of the poems in the 1798 edition were written by Wordsworth; Coleridge has only four poems included, one being his most famous work, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

Here is a link to the full-text of “Tintern Abbey” that so moved Mary: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45527/lines-composed-a-few-miles-above-tintern-abbey-on-revisiting-the-banks-of-the-wye-during-a-tour-july-13-1798

*********************

William Godwin. Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness. London, 1793. [Godwin, it is worth noting, married Mary Wollstonecraft and was the father of Mary Godwin Shelley]. Outlines Godwin’s radical political philosophy.

William Godwin (portrait by James Northcote) and Mary Wollstonecraft (portrait by John Opie) – from BrainPickings.org

************

Machiavelli – is referred to by Mary, so assume she is familiar with his The Prince (1513).

****************

Image: Guide to the Lakes. ‘View on Winandermere’ [now called Windermere], by Joseph Wilkerson. Romantic Circles

******************

John Milton. Paradise Lost. A mention by Mr. Ryder who is defeated by its length, so we know Mary was familiar with it.

***********

The Edinburgh Review / The Quarterly Review – brought to Mary by Mr. Ryder, and for which Mr. Hayward perhaps wrote his reviews. The Edinburgh Review (1802-1929); Quarterly Review (1809-1967, and published by Jane Austen’s publisher John Murray) – both were very popular and influential publications of their time…

*********************

The Other Bennet Sister is an enjoyable read – it is delightful to see Mary Bennet come into her own, that despite what she viewed as an unhappy childhood, she finds her way through a good number of books in a quest to live a rational, passionless existence. And that the development of some well-deserved self-esteem with the help of various friends and family, might actually lead her to a worthy equal partner in life, just maybe not with Mrs. Bennet’s required £10,000 !

- Here is an excellent review of the book at The Christian Science Monitor: https://www.csmonitor.com/Books/Book-Reviews/2020/0408/The-Other-Bennet-Sister-focuses-attention-on-bookish-Mary

- And an interview with the author at NPR: https://www.npr.org/2020/04/09/830069319/elizabeths-more-serious-sister-mary-takes-the-spotlight-in-the-other-bennet-sist

©2020 Jane Austen in Vermont

Looking for Jane Austen’s Pemberley ~ Guest Post by Chris Sandrawich

Dear Readers: I welcome today my good friend Chris Sandrawich, who has posted here before on all things Jane Austen and the Regency world. This post on “Looking for Pemberley” was originally published in the JAS Midlands annual publications Transactions (No. 24, 2013), so I am honored to include it here on the blog where it might get a well-deserved wider readership. Chris’s usual insights and wit would, I believe, even delight our not-for-dull-elves Jane. Hope you enjoy it as much as I have – please comment below with any thoughts or questions you might have for Chris. [Please note that I have maintained Chris’s British spelling and punctuation!]

******

Looking for Pemberley

by Christopher Sandrawich

This article, in the nature of a ‘Quest’, is meant to half serious and half fun, and I apologise in advance for any difficulty in working out which half is which. It is a doomed quest because Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy along with Pemberley are all fictional and I apologise if any of your illusions have just been shattered. In “Looking for Pemberley” I was also diverted from this topic firstly by the River Trent and then by the Rutland Arms in Bakewell and so both will feature very largely in what I have to say.

I confess to being absolutely certain when I began this research that the popular choice of Chatsworth would not prove a very realistic proposition. However, I tried to keep an open mind. It fails primarily on economic grounds. Chatsworth is a palace, like Blenheim Palace or Warwick Castle. It is obviously the home of an aristocrat, with a very large income needed to run it. Our hero, Darcy is just plain “Mr”, but he is alluded to as someone who could be, “reasonably looked up to as one of the most illustrious personages in this land” by Mr Collins who likes to get his facts right, and so there is some room for doubt. We’ll see as this paper mirrors the trail of research I followed, that my view has, “been shifting about pretty much” like Elizabeth says in her explanation to Jane concerning her varying feelings about Wickham and Darcy. However, Jane Austen when creating her fiction had a perfect right to have none, one or a dozen gentlemen’s country homes in mind.

We have a few pointers on how Jane Austen found material for her novels. Gaye King, a former Chairman of The Jane Austen Society Midlands, discovered that Jane Austen stayed with her cousin the Rev Edward Cooper and his family, at Hamstall Ridware in Staffordshire, directly after visiting Stoneleigh Abbey. We can match

- Colonel Brandon’s Delaford in Sense and Sensibility with the Parsonage at Hamstall Ridware,

- Stoneleigh Abbey itself with Northanger Abbey and

- Stoneleigh Abbey’s chapel with that described in Mansfield Park and found in Mr Rushworth’s country home Sotherton. The landscaper Repton is the only one mentioned in any of the books and he worked on Stoneleigh Abbey and is the landscaper suggested for Sotherton.

Also, we have character’s names. Anyone who has read Sense and Sensibility will be interested in hearing that in addition to Colonel Brandon’s Delaford with its great garden walls, dovecote and stewponds matching Edward Cooper’s Rectory we have people known to, or friends of, the Coopers: Ferrars spelt with two “e’s” but still with an ‘F’, Dashwood, Palmer, and Jennings. Also, the Austens would have passed through Middleton on their journey from Stoneleigh Abbey in Warwickshire to Hamstall, and in addition Lord Middleton was a distant relation of Mrs Austen and she, herself, was named after the sister of the first Lord Middleton – Cassandra Willoughby. There we have six characters in the book straight off.

So Jane Austen has a proven track record, just like other novelists, of borrowing scenes and people from her memory when writing her novels and with the places mentioned above we have it on record that she visited them. Did our Jane go into Derbyshire? This is a good question and one which we will consider.

Rebecca

Rebecca may seem an odd place to start but I have my motives. Daphne du Maurier wrote Rebecca which was published in 1938 when she was in Alexandria, Egypt, where her husband was posted. What a lot of people do not know is that before she went to Egypt, Daphne du Maurier was travelling in Derbyshire with an Aunt, on her Father’s side, and she had sat up late one night in her hotel bedroom reading Pride and Prejudice.

Rebecca may seem an odd place to start but I have my motives. Daphne du Maurier wrote Rebecca which was published in 1938 when she was in Alexandria, Egypt, where her husband was posted. What a lot of people do not know is that before she went to Egypt, Daphne du Maurier was travelling in Derbyshire with an Aunt, on her Father’s side, and she had sat up late one night in her hotel bedroom reading Pride and Prejudice.

When she joined her Aunt for breakfast next morning, just as coffee was being poured, she said, “Last night I dreamt I went to Pemberley again”, but her Aunt who was hard-of-hearing and had lived in the far east, replied, “What was that dear, Manderley?” thinking no doubt of the similarity with the road to Mandalay . . . . . . . and so one of the great opening lines of a novel was born, “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again”, and Daphne, borrowing a napkin from the maid, wrote it down there and then.

So we can see that the closeness in spelling, and the shape of the word, between Manderley and Pemberley is not just co-incidental after all. I owe this information to my Uncle Jim whose best friend Eric’s mother Edith was the very lady pouring the coffee and passing napkins as a maid in that very same hotel.

Now if you suggest that I have just made all this up, as indeed you might, then I may reply as did Pooh-Bah in the Mikado, “Merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic veri-similitude to a bald and unconvincing narrative.” And I hope to avoid molten lead, as he was promised, for my pains. I fully expect that if this news spreads far and wide that plaques on hotel walls all over Derbyshire will appear claiming they were the very hotel where Daphne stayed and that they have her copy of Pride and Prejudice left by the bedside to prove it. Just why I have been involving us all in a flight of fancy will hopefully become clear later. People make things up you know!

As I mentioned above Rebecca was published in 1938 and was then adapted for film in 1940.

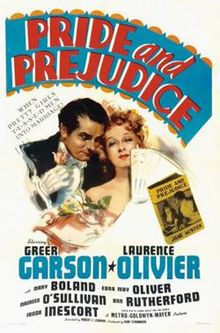

Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice was published two hundred years ago in 1813. Helen Jerome adapted it for the stage in 1935, and a Broadway musical First Impressions sprang from that. Helen Jerome’s adaptation was used again in 1940 for the film starring Laurence Olivier as Darcy, and a much too mature Greer Garson, as Elizabeth.

Pride and Prejudice was published two hundred years ago in 1813. Helen Jerome adapted it for the stage in 1935, and a Broadway musical First Impressions sprang from that. Helen Jerome’s adaptation was used again in 1940 for the film starring Laurence Olivier as Darcy, and a much too mature Greer Garson, as Elizabeth.

We won’t find Pemberley on a 1930’s Broadway stage and we can look in vain at the MGM film for it too. The nearest we get is an indoor scene were Bingley, distracted by his sister’s disparaging remarks about Jane and Elizabeth, plays a false shot and rips Darcy’s billiard table cloth. The whole room at Pemberley, as well as Meryton and Longbourn, were the product of the work of carpenters on MGM’s Hollywood studio lots. This adaptation did not even include the Gardiners.

TV Miniseries: Darcy and Elizabeth

After this film we have a glut of Television Miniseries appearing in the 1950’s and 1960’s (one in Italian and one by the Dutch which I shall skip over) and we do have interesting UK pairings for Darcy and Miss Elizabeth Bennet:

- 1952 Peter Cushing and Daphne Slater

- 1958 Alan Badel and Jane Downs

- 1967 Lewis Fiander and Celia Bannerman

Which, I believe, are all BBC productions: in those days ITV saw a limited audience for expensive to produce “costume-drama”, and as all the action on TV takes place in-doors we have no large buildings to show.

We have not time to see them all but I could not resist finding a picture of Peter Cushing suitably dressed for his part of Darcy, which he would have played when 39 years of age.

Notable points emerging from the Outside

We are going to look at houses used in TV adaptations and in films. It will be interesting to compare the features presented by these choices with the novel’s description so when you view the houses try and put a mental tick against any point in favour of the house as a reliable model for Pemberley.

- Pemberley stood on the opposite side of a valley when first seen

- Large handsome stone building

- Standing well on rising ground

- Backed by a ridge of high woody hills

- In front a stream of some natural importance (that) has swelled into greater

- Without any artificial appearance

- They descended the hill crossed the bridge and drove up to the front door

Notable points emerging from the Inside

Inside from a window Lizzy Bennet’s prospect was

- The hill, crowned with wood from which they had descended receiving increased abruptness from the distance

- The river, the trees scattered along its banks

- The winding of the valley as far as she could trace

So, what we should be looking for is a house that matches as many of these ten key points as possible. Many of them only manage one, and we begin with:

Renishaw Hall

Renishaw Hall, in Derbyshire, was used as Pemberley for the 1980 BBC TV adaptation starring David Rintoul as Darcy and Elizabeth Garvie as Lizzy Bennet. The Sitwell fortune was made as colliery owners and ironmasters from the 17th to the 20th centuries, and Renishaw Hall has been the Sitwell family home for 350 years. The Bingley sisters can be as “sniffy” as they like about money arising ‘from trade’, and be hypocritical when doing it, but most of the aristocratic families had land and capital and they used old money for trade to make new money. The beautiful gardens you can see, including an Italianate garden, are open to the public.

Lyme Hall

Lyme Hall, Disley, is in Cheshire, and was used as Pemberley in the now quite famous 1995 BBC adaptation starring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth (which lady can ever forget his wet shirt). The house is the largest in Cheshire and is now owned by the National Trust. It had been in the Leigh family’s possession from 1388 until 1948.

The clever angle of the TV camera, as the Gardiner’s carriage stops and Lizzy takes her first look at “Pemberley”, made the stretch of water in front of the house look as much like a river as possible but it is of course more accurately described as ‘a large pond’.

Wilton House

For the 2005 P&P Wilton House near Salisbury in Wiltshire was used for many of the interior scenes (photograph by John Goodall).

Wilton House is situated near Salisbury in Wiltshire. It has been the country seat of the Earls of Pembroke for over 400 years. Now when you look at this house you may be wondering in which Pride and Prejudice you have seen it. Well, you haven’t seen the outside view BUT when Elizabeth and the Gardiners go into Lyme Hall they are seen inside Wilton House instead. A typical illusion pulled off with ease by TV and filmmakers and unless you are familiar with these homes you might never know.

There is a clue to this “switch” for the very observant; when Elizabeth, at the front of the house, takes in the view outside from the window the “lake” has trees along its nearside whereas Lyme Park does not.

Chatsworth House

Chatsworth House in Derbyshire is one of England’s most famous country homes and is owned by the Duke of Devonshire. Chatsworth was used as Pemberley in the 2005 film version starring Matthew Macfadyen as Darcy and Keira Knightley as Elizabeth Bennet.

Chatsworth House in the 18th C

This painting (by William Marlow) gets us as close to seeing how Chatsworth looked when the 6th Duke inherited Chatsworth in 1811. Earlier works show bare-headed hill tops behind and so you will notice that there has been a lot of tree planting on the higher ground. We can see that the terrain Chatsworth stands in seems more sharply rising than the others.

So is Chatsworth Pemberley? Well let’s take a closer look at the 6th Duke and remember that Chatsworth is not really a house at all but like Blenheim, it is a Palace. Could Darcy on only £10,000 yearly income (even if it was very likely more as Mrs Bennet cheerfully speculates) manage such a home? It is difficult if not impossible to imagine how this level of income compares to today’s standards as lifestyles have changed so much. If we look at the RPI then £10,000 looks like only £500,000 in today’s purchasing power but if instead we look at the growth in earnings then £10,000 gets close to £8,000,000 so you can see the difficulties. Take your pick, but if a Curate could manage on £50pa then £10,000 is relative wealth two centuries ago.

A popular myth these days is that Darcy was one of the richest people in England. Afraid not, if he was on only £10,000 yearly, Jane’s brother Edward, adopted by the Knight family, had an income of £15,000pa and mere farmers to be found everywhere could have incomes of £10,000 to £40,000pa.

Louis Simond a Frenchman living in New York with his English wife toured England in 1811 – 12 and wrote an interesting sharply observed journal, which is full of facts and figures. He quotes the value of farmland in England at the time as 40/- to 45/- an acre for rent. Now if you worked the land you were expecting a profit so an acre would actually yield a larger income than the rents.

The 6th Duke owned 3 houses in fashionable London and many great estates in England and one in Ireland with a combined size of 200,000 acres. In Derbyshire he had 83,000 acres. Now not all the Duke’s land would be useable farmland and he would have had hills, woods and boggy ground eating into his farming income. But let us not forget that his powerful ancestors were amongst the first-comers and all the estates were set in favourable local conditions; so an estimate of 50% of his lands being utilised for farming could actually be conservative. Taking the mid-value of Louis Simond’s range and this estimate of the 6th Duke’s farming lands we can estimate his income as over £200,000pa.

Having done this exercise it is most disappointing to find that the Duke’s income for the period was assessed as only £70,000 yearly. Donald Greene quotes this on page 316 and gives his source as David Cannadine’s book, “The Landowner as Millionaire: The Finances of the Dukes of Devonshire”. This £70,000 yearly, after various mortgages and jointures were paid, left him with only with “a clear” £26,000 pa. Where might the discrepancy be? After all, if only £70,000 is drawn from over 200,000 acres then we conclude that only one-sixth of the land was rented for farming leaving five-sixths unutilised which seems untenable as a proposition and seems very unlikely behaviour from a Duke encumbered with debts not to instruct his servants to maximise his farming income.

The Duke’s estates were large and widespread and he would have to rely on stewards and many others in the management of these estates, so I am reminded of the second of Mr Bennet’s remarks to Jane on her engagement to Bingley. “You are each of you so complying, that nothing will ever be resolved on; so easy, that every servant will cheat you; and so generous, that you will always exceed your income.” But “cheating” on this massive scale seems unlikely as well, as how could such a small group of servants disguise, hide or profit from this wealth without drawing attention to themselves. So for me the suggested shortfall in income remains a mystery.

Harewood House

Harewood House is near Leeds in West Yorkshire and it was built from 1759 to 1771 for wealthy trader Edwin Lascelles, 1st Baron Harewood, and is still home to the Lascelles family. It was used as Pemberley in the ITV series “Lost in Austen” starring Jemima Roper as the ‘lost girl’ who eventually swops fates with Elizabeth, played by Gemma Arterton, and gets to marry Darcy played by Elliot Cowan. I personally really enjoyed the series, fanciful though it was.

How are your mental scores or ticks for the various houses going? Well we have run out of houses to look at as shown on TV and Film but we are still on our quest, and Chatsworth for me, is the only one we have seen which matches the novel’s description.

My next step is to look at the thoughts on “Where is Pemberley” amongst many eminent authors and scholars who were giving this subject a lot of thought in the 20th Century and who are now sadly no longer with us.

Elizabeth Jenkins

Elizabeth Jenkins died in 2010 aged 104, and she was a very distinguished novelist and historian and whose research for Jane Austen A Biography published in 1938 makes it still a very widely regarded work.

Elizabeth Jenkins died in 2010 aged 104, and she was a very distinguished novelist and historian and whose research for Jane Austen A Biography published in 1938 makes it still a very widely regarded work.

In 1958 she saw, in the Rutland Arms, Bakewell, a Notice making claims about Jane Austen staying in a room there whilst revising her novel Pride and Prejudice in 1811. She was “taken aback by these statements” and she could not get the author, Elizabeth Davie, who claimed the Bakewell: Official Guide, and by inference Mr V R Cockerton who wrote the introduction which Ms Davie quotes from pretty much word for word, as a reliable source for her claims, to retract them over exchanges lasting 6 or 7 years on and off. Elizabeth Jenkins never did get hold of a copy of the Bakewell Official Guide and in turn pursue Mr Cockerton, which is unfortunate as I have found all trails now run cold.

It is well worth mentioning that the latest Official Guide to Bakewell now says under a photo of the Rutland Hotel, and I quote, “William Wordsworth and J M W Turner were among the famous who visited the hotel. Jane Austen, contrary to popular story, did not; Pride and Prejudice was not written here and she is not known to have visited Derbyshire.” If you visit the Rutland Arms as I did only this year and enquire you will be confidently assured that Jane Austen stayed there and that there is a Notice about it that anyone can view. Hotel Staff do not know who wrote the notice, or that its original source was out-of-date editions of the Official Guide to Bakewell. They are further unaware that the same Guide now flatly refutes this assertion. They remain blissfully ignorant, but are very nice about it.

Getting back to the fifty year old dispute between Elizabeth Jenkins and Elizabeth Davie, the impasse reached led to Elizabeth Jenkins publishing an article in the JAS Report 1965 supported by the whole Jane Austen Society Committee rebutting the Notice’s claims saying they are entirely without foundation.

Strong stuff; but what exactly did the Notice say? Let’s look at the Rutland Arms.

Rutland Arms: Bakewell

Here is a side-view of the hotel in Bakewell called the Rutland Arms and it seems hardly likely to be the centre of a major literary controversy. Behind those walls we can find what the Notice says, and despite Elizabeth Jenkins best efforts it is still there?

The Notice was originally displayed right outside Bedroom No 2 (in the photo first find the door, then the window above; now go to the window on the left and you have Bedroom No 2). The Notice is now sited in the Reception area, and I write it out and put some stress on the contentious parts which will be discussed later:

In this room in the year 1811, Jane Austen revised the manuscript of her famous book “Pride and Prejudice”. It had been written in 1797, but Jane Austen who travelled in Derbyshire in 1811 chose to introduce the beauty spots of the Peak into her novel. The Rutland Arms Hotel was built in 1804, and while staying in this new and comfortable inn we have reason to believe that Miss Austen visited Chatsworth only three miles away and was so impressed by its beauty and grandeur that she made it the background for Pemberley, the home of the proud and handsome Mr Darcy hero of “Pride and Prejudice”.

The small town of “Lambton” mentioned in the novel is easily identifiable as Bakewell, and any visitor driving thence to Chatsworth must immediately be struck by Miss Austen’s faithful portrayal of the scene —— the “large handsome stone building, standing well on rising ground and backed by a ridge of woody hills”. There it is today, exactly as Jane Austen saw it all those long years ago.

Elizabeth Bennet heroine of the story had returned to the inn to dress for dinner, when the sound of the carriage drew her to the window. She saw a curricle driving up the street, undoubtedly Matlock Street, which these windows overlook, and presently she heard a quick foot upon the stair, the very staircase outside this door.

So, when visiting this hotel and staying in this room, remember that it is the scene of two of the most romantic passages in” Pride and Prejudice” and “Pride and Prejudice” must surely take its place among the most famous novels in the English Language.

Rutland Arms Brochure

It is possibly all for the best that Elizabeth Jenkins did not see the new brochure, because there is more. In the 1960’s the inn was owned by Stretton’s Derby Brewers Ltd, but the last time I looked it was owned by David Donegan, a retired solicitor. The brochure says (and I could only see the on-line version as they were waiting for a fresh package from their printers), and hang onto your hats while I quote from it,

“The Rutland has played host to several celebrated guests in its long history. Jane Austen stayed here in 1811 while revising her novel ”Pride and Prejudice”, using her room as the background for two scenes in the book and engraving sketches in the glass, still visible today”

The idea that Jane Austen would etch something on the windows of an Inn I find simply startling, and wonder just how this new information has come to light since the original Official Guide and the Notice. It seems obvious that the Hotel have not read the current Official Guide or remember hearing from Elizabeth Jenkins.

Objections to the Notice

Elizabeth Jenkins attacked the Notice on three main issues:

[ 1 ] She recited all of the reasons already mentioned why a Palace like Chatsworth is outside Darcy’s league, although she conceded the similarities in appearance, but she counters that there are in England many other houses that are a reasonable fit for ‘Pemberley’ too.

[ 2 ] Bakewell is NOT Lambton. A careful reading of the novel reveals that the Gardiners and Elizabeth are staying in Bakewell and when discussing their next step to visit Mrs Gardiner’s friends in Lambton they choose a route so as to see Pemberley on their way.

We will identify where Lambton, a fictitious Town might be later, but the novel indicates a three mile plus journey from Bakewell to Pemberley and then a five and a bit mile stretch to Lambton from there. We can have some fun at the Film and TV Adaptations’ expense now as some of them share this confusion between Bakewell and Lambton and the relative distances.

In the Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson film they neatly avoid all issues by omitting the Gardiners and the trip to Derbyshire altogether.

In the David Rintoul and Elizabeth Garvie TV Adaptation Lizzy is seen reading Jane’s letters revealing Lydia’s elopement while in their rooms at the Inn in Lambton and snatching up her hat and shawl she is seen running out of the room and then onto the approaches to Pemberley and into the House. This sequence gives the idea that this is no big deal and Elizabeth is only slightly breathless. Now I know that Elizabeth Bennet is fit, but five miles across undulating country – in the height of mid-summer – and encumbered with a long dress and petticoats and all the while clutching her letters! Suspend disbelief if you can.

This running is catching. In the Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth version we have the Gardiners already staying in Lambton, so the rationalé behind their visit to Pemberley no longer holds. But leaving that aside, when Mrs Gardiner mentions Lambton we see Darcy’s eyes light up and he describes how, when a young boy, he ran to the village green in Lambton to a tree by the smithy every day in the horse-chestnut season. I think that bit isn’t in the book because Jane Austen would reckon no boy of sense runs over ten miles daily to get conkers when he could get all he could carry within a few hundred yards of home. Unless, of course, stealing the village boys’ conkers was his aim.

In the Keira Knightley film version her Aunt and Uncle, from whom she was temporarily separated, inexplicably leave her behind at Pemberley, which seems excessively harsh treatment for not ‘keeping-up’. Lizzy refuses Darcy’s help with transport and says she’ll walk. She has never been to Lambton in her life let alone to Pemberley and to this part of Derbyshire but she boldly sets off across five miles of rough country beginning with crossing the Derwent and climbing out of the steep valley Chatsworth is in. The film shows her crossing fields and not following any path. Not only did she mystically pick exactly the right direction but without any roads or signposts to help she unerringly finds The Rose and Crown in a small town in the middle of nowhere.

Sorry, for the diversion, back to Elizabeth Jenkins and her next point.

[ 3 ] She consulted the foremost authority at that time on all things Austen, Dr R W Chapman at Oxford with the question of Austen touring Derbyshire. He replied, “no evidence that she was ever north of the Trent”.

That was enough for Elizabeth Jenkins but some other smaller details in the Notice took my eye and I’ll share them with you.

[ 4 ] Two of the most romantic scenes in the novel! Well I do not think so. Let’s have a look at Bedroom No 2 which is where the visits occur. The room is very small but it has to be this room as it is adjacent to the stairs, and it is believed to have been permanently connected to the room next along, from which it is now divided by doors, and used as a Reception Room. It will help if we mentally ignore the décor and remove the bed. I can also imagine the sucking in of breath over teeth for any builder asked to enlarge a room that has two outside walls, one wall leading onto a landing and the last wall being almost all chimney breast for the large fireplace downstairs which was there when the hotel was built. I asked. So by the time we put in a table large enough for six along with chairs it will look cramped in this half of the reception room. Of course, as Jane Austen was making it all up, and if using the Rutland Arms as her model, then all she had to do was ‘imagine’ it large enough.

In the novel it holds Elizabeth with her Aunt and Uncle, although Ms Davie clearly leaves out the Gardiners in her depiction, and when the curricle arrives it rapidly fills up, first with Darcy and his sister, Georgiana, and then Bingley who joins them afterwards. A fraught and tense introductory meeting, yes; but not the stuff of romance.

The only other meeting taking place would be when Jane’s letters about Lydia’s elopement with Wickham have upset Elizabeth, and Darcy unexpectedly arrives and gives what help and comfort he can until the Gardiners return. For most of the time Darcy and Elizabeth are both very much preoccupied and caught up in their private thoughts and concerns. Romantic? Hardly; when he leaves Elizabeth never expects to see Darcy again!

[ 5 ] She heard Darcy’s quick foot on the stairs. The novel does not mention this but it does with Bingley’s arrival, when it is “Bingley’s quick step was heard on the stairs.”

[ 6 ] My last problem with the Notice is over ‘line of sight’. Here we have a view from the window, which is not the one you saw at the side of  the Rutland Arms as this window looks out of the front of the hotel. Elizabeth Davie has Lizzy Bennet noticing the curricle arriving, and it would help considerably if the street you can see outside was Matlock Street. The Devil is in the detail they say. The street outside, running towards the front of the hotel, is Rutland Square and that is definitely the one you take to get to Chatsworth House which is to the east of Bakewell. Matlock Street is the A6 running broadly north to south and, apart from the first few yards, it is well out of sight and bending away from the right-hand side of this window. Matlock Street unsurprisingly goes south to Matlock and getting further away from Chatsworth with every yard.

the Rutland Arms as this window looks out of the front of the hotel. Elizabeth Davie has Lizzy Bennet noticing the curricle arriving, and it would help considerably if the street you can see outside was Matlock Street. The Devil is in the detail they say. The street outside, running towards the front of the hotel, is Rutland Square and that is definitely the one you take to get to Chatsworth House which is to the east of Bakewell. Matlock Street is the A6 running broadly north to south and, apart from the first few yards, it is well out of sight and bending away from the right-hand side of this window. Matlock Street unsurprisingly goes south to Matlock and getting further away from Chatsworth with every yard.

Now we must remember that Georgiana only arrived with a large party in time for a late breakfast and they arrive to see Elizabeth before dinner, so that means Georgiana has only had a brief time to eat, change and collect herself before getting into the curricle with her brother. It would be unreasonable to suppose that she would have wanted to go sightseeing, or take a detour. So for Elizabeth Davie to be right, and for Darcy’s curricle to be coming up Matlock Street, we must accept the unlikely premise that Darcy has completely lost his way within three miles of his birthplace and home.