We had our JASNA-Vermont gathering last Sunday and Mary Ellen Bertolini of Middlebury College spoke on Persuasion [see Kelly’s post below on our event]

We had our JASNA-Vermont gathering last Sunday and Mary Ellen Bertolini of Middlebury College spoke on Persuasion [see Kelly’s post below on our event]

Mary Ellen brought Austen’s final novel to life for us all. In speaking on “The Grace to Deserve” and taking as her starting point Captain Wentworth’s last spoken words in the book, “I must learn to brook being happier than I deserve.” [Persuasion, ch. 23], she addressed the issue of “deserving” and “earning ones’ blessings” in the context of the social and political realities of the time – the war in France and the role of the Navy; an analysis of the criteria of WHO deserves; and finally in the linguistics of the work – whose words deserve to be heard? The plot centers on Anne moving from “nothingness” and” carrying “no weight” to realizing her own worth, and Wentworth moving from anger and disappointment to deserving to hear Anne’s words – their individual growth bringing them together at last.

Prof. Bertolini’s insightful, dramatic and often humorous presentation on how Austen tells her tale around these three words “the grace to deserve” gave all in attendance much to think about and surely most of us went right home to begin a re-read of the novel! So we thank you Mary Ellen for sharing your affection for this book with all of us, and turning a very cold winter day into a fabulous afternoon!

**************************************

As a bookseller and librarian I am interested in the publishing history of the literature of the 18th and 19th centuries, and I spoke very briefly on the publishing journey of Persuasion; I append that here:

We know from Cassandra’s Memorandum [see Minor Works, facing pg. 242 ] in which she wrote the dates of Austen’s composition of each of her novels, that Jane Austen began Persuasion on August 8, 1815; it was finished July 18, 1816 – i.e. her first draft. We know she was unhappy with the ending, she thought it “tame and flat” and rewrote chapter 10 [i.e.chapter 10 of volume 2], added chapter 11, and retained chapter 12 (which had been the final chapter 11). This final version was finished on August 6, 1816. The manuscript of the original two chapters are the ONLY extant manuscripts of Austen’s novels. These were first printed in the second edition of James Edward’s Austen-Leigh’s Memoir of 1871, and this was the accepted text until the actual MS became available on December 12, 1925 [ published separately by Chapman in 1926 under the title Two Chapters of Persuasion [Oxford, 1926]; the manuscripts are housed in the British Library]. This text is different from the printed cancelled chapter in the Memoir – so it is believed that Austen made a fresh copy of her final draft and this is what went to the printer. [Chapman, NA & P, p. 253 ]

I am assuming that most everyone has read these cancelled chapters, as they are usually included in most printings of the novel. But to summarize: Austen has Anne meeting Admiral Croft on her way home from Mrs. Smith’s [where she has just learned the true nature of William Elliot] – she is invited to visit Mrs. Croft, and assured of her being alone, she accepts, and to her consternation finds Capt. Wentworth at home. Admiral Croft has asked Wentworth to find out from Anne if the rumors are true she is to marry her cousin and thus might want to live at Kellynch Hall ~ and with Anne’s adamant denial of this, Wentworth and Anne had a

silent but very powerful Dialogue;- on his side, Supplication, on hers acceptance. – Still, a little nearer- and a hand taken and pressed – and “Anne, my own dear Anne!” – bursting forth in the fullness of exquisite feeling – and all Suspense & Indecision were over. – They were reunited. They were restored to all that had been lost.

Etc. etc… and then one more chapter of explanation and future plans.

It is not my intention here to talk about these changes – we can argue the point of why she made them: the need to pull all the characters together – the Musgroves, Benwick, & Harville, the Crofts, and the Elliots; the increased tension and suspense between Anne and Wentworth; Anne’s conversation with Harville overheard by Wentworth; and of course the LETTER – what would Persuasion be without “you pierce my soul” ? !

However, in the movie version [Amanda Root – Ciaran Hinds, Sony/BBC 1995] a part of this scene with Wentworth confronting Anne is added to the plot – this is worthy of some further conversation!

But one of Austen’s classic lines is not in the final novel – the first draft is a bit more comic in nature, and perhaps she thought it not fitting the rest of the work:

It was necessary to sit up half the Night & lie awake the remainder to comprehend with composure her present state, & pay for the overplus of Bliss, by Headake & Fatigue.

____________________________________________

That Austen made these changes was a gift to later generations, as it is in this manuscript that we have the only documentation of how meticulous she was in her writing and editing methods. And what I find most fascinating is what she was working on at the same time:

*In 1815, she was drafting Emma; began Persuasion in August; revised Mansfield Park for its 2nd edition; and finished and passed Emma through publication [it was published in December 1815]

*In 1816: she was drafting and finalizing Persuasion; she wrote her very funny “Plan of a Novel”; she made revisions to “Susan” [later Northanger Abbey]; AND she was working with the publisher on the 3rd edition of Pride & Prejudice.

As an aside: in the context of the wider world, there was the ever-expanding and more competitive market for publishing novels in Austen’s time. In 1775, the year she was born, 31 new novels were published; in 1811, when Sense & Sensibility appeared, 80 new fiction works appeared; for the year 1818, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion were published along with 61 other novels. Altogether, 2,503 new novels were published in the years between 1775 and 1818. [Raven, p. 195-6]

We know little about Persuasion from Austen herself: it is only mentioned in her Letters twice, though not by name:

On March 13, 1817, she wrote to her niece Fanny Knight:

“I WILL answer your kind questions more than you expect. – Miss Catherine [meaning Northanger Abbey] is put upon the Shelve for the present, and I do not know if she will ever come out; – but I have a something ready for Publication, which may perhaps appear about a twelvemonth hence. It is short, about the length of Catherine – This is for yourself alone…” [Letter 153, Le Faye]

And again on March 23, 1817:

Do not be surprised at finding Uncle Henry acquainted with my having another ready for publication. I could not say No when he asked me, but he knows nothing more of it. – You will not like it, so you need not be impatient. You may PERHAPS like the Heroine, as she is almost too good for me. [Letter 155, Le Faye]

The working title for Persuasion was “The Elliots” – there is no evidence that Austen chose the titles for either Northanger Abbey [it is accepted that her brother Henry did this] or Persuasion [though the word is mentioned in one form or another more than 20 times – you can go to this link at the Republic of Pemberley for all the occurrences]

So, the details of the book:

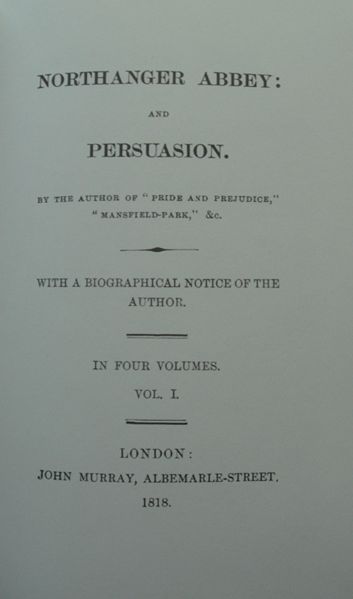

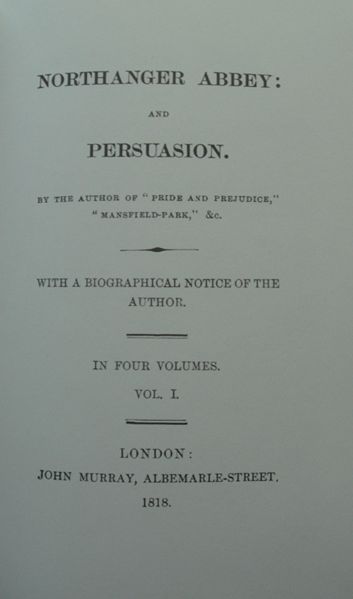

[Title Page, 1st edition]

-It was published posthumously in December 1817 [though the title page says 1818] with Northanger Abbey

– Title page states: “By the Author of Pride & Prejudice, Mansfield Park, etc.”; With a Biographical Notice of the Author [dated Dec. 20, 1817, by Henry Austen, thus identifying his sister as the author to the public for the first time]

-Included is the “Advertisement to Northanger Abbey by The Authoress [we discussed this at our NA gathering, where Austen “apologizes” for the datedness of the story, and zings the dastardly publisher for withholding the book for 10 years…]

–Published by John Murray, London; 1818; in four volumes: the two Northanger Abbeyvolumes printed by T. Davison; the two Persuasion volumes by C. Roworth.

– Advertised in the Morning Chronicle, Dec. 19 & 20, 1817

-Physical description:blue-grey boards, brown paper backstrips, white paper labels (there are a few variants)

–Size of book: about 19cm x 10.5 cm [ 7.5 x 4.25″]

– Size of run: @ 1750 copies [various opinions on this] – 1409 copies sold very quickly [majority to circulating libraries]

–Cost: 24 shillings for 4 volumes

–Profit: £515 [like Austen’s other works, Persuasion was published on commission: Austen paid for costs of production and advertising and retained the copyright; the publisher paid a commission on each book sold – exception was Pride & Prejudice for which she sold the copyright]

-Reviews: minor notices until the first extensive review in January 1821.

-Worth today: a quick search brought up 7 copies of the 4-vol. first edition, all have been rebound in leather, range $9500. – $15,000.

-Tidbit: the Queen has in her personal library Sir Walter Scott’s copy of the 1st edition.

–First American edition: not published until 1832 in Philadelphia; the title page says “by Miss Austen, author of P&P and MP, etc.”

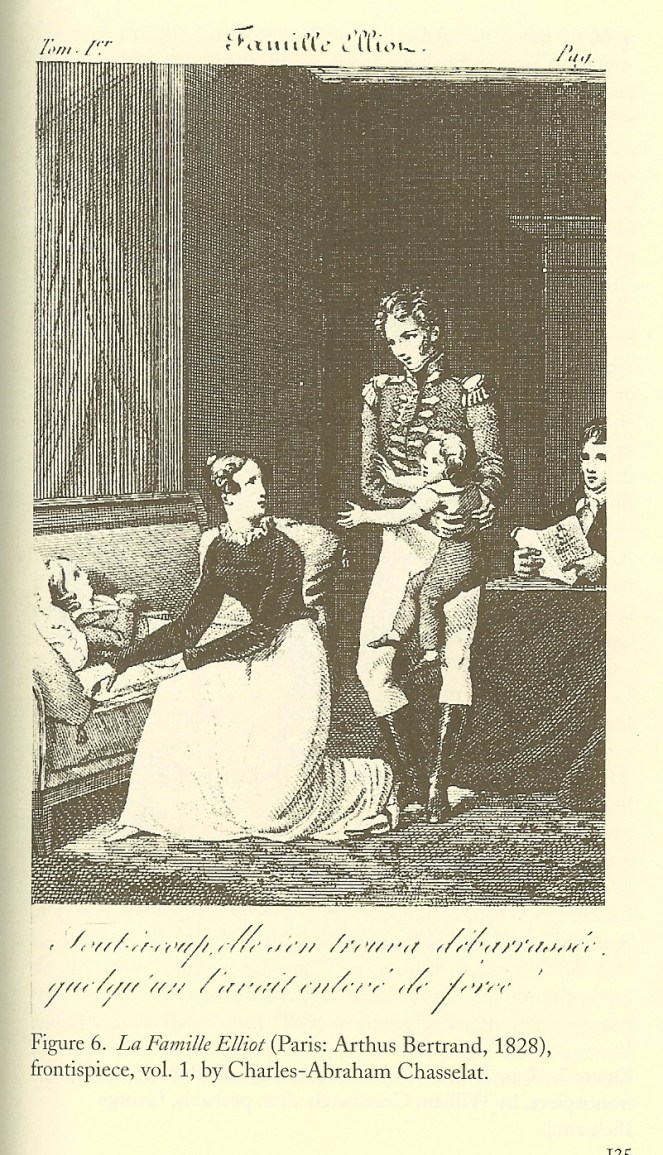

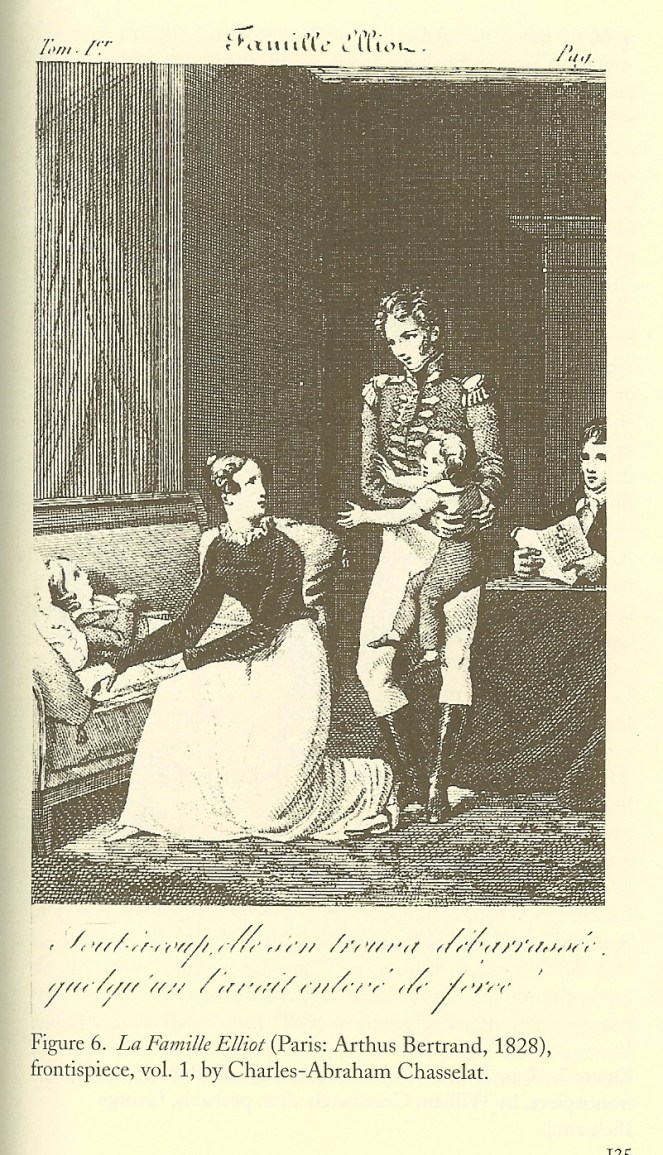

-French Translation: La Famille Elliot ou “L’Ancienne Inclination” [ the old or former inclination] translated by Isabelle de Montolieu, Paris, 1821 : this is the first published Austen work to have her full name on the title page and to include illustrations: in vo1 1, Wentworth removing Walter Musgrove from Anne [see below]; vol 2: Wentworth placing his letter before Anne.

[Source: Todd, p. 125] Anne was called Alice; one aside about these translations: Baroness de Montolieu took liberties with the text : made them more sentimental for the French audience – but this too is a topic for another discussion!

Sources:

- Chapman, R.W. The Novels of Jane Austen: the Text Based on Collation of the Early Editions. 3rd ed. Vol. V, Northanger Abbey & Persuasion, Oxford, 1933. [with revisions] Introductory material.

- Gilson, David. A Bibliography of Jane Austen. Oak Knoll Press, 1997.

- Raven, James. “Book Production.” in Janet Todd, ed. Jane Austen in Context. Cambridge, 2007.

Many of us who grew up in the late 40s – early 50s had our Jane Austen force-fed to us in high school (unless we were fortunate enough to be blessed with an Austen-loving mother or father!). Pride & Prejudice was the standard text with little reference to the other works; followed by George Eliot’s Silas Marner, Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities and / or Great Expectations, Shakespeare (hopefully!), and Hemingway, Steinbeck, Salinger for contemporary authors. But I’ve often thought that Austen got a bum-rap with this “required-reading” status, the educational system’s way of compensating for what an early critic said in calling Austen “a critic’s novelist – highly spoken of and little read.” [p. 120] And while I am the first to admit that Austen is not for everyone [their terrible loss!], I have long believed that this approach to Austen added to her suffering from the great reader-turnoff.

Many of us who grew up in the late 40s – early 50s had our Jane Austen force-fed to us in high school (unless we were fortunate enough to be blessed with an Austen-loving mother or father!). Pride & Prejudice was the standard text with little reference to the other works; followed by George Eliot’s Silas Marner, Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities and / or Great Expectations, Shakespeare (hopefully!), and Hemingway, Steinbeck, Salinger for contemporary authors. But I’ve often thought that Austen got a bum-rap with this “required-reading” status, the educational system’s way of compensating for what an early critic said in calling Austen “a critic’s novelist – highly spoken of and little read.” [p. 120] And while I am the first to admit that Austen is not for everyone [their terrible loss!], I have long believed that this approach to Austen added to her suffering from the great reader-turnoff.

We had our JASNA-Vermont gathering last Sunday and Mary Ellen Bertolini of Middlebury College spoke on Persuasion [see

We had our JASNA-Vermont gathering last Sunday and Mary Ellen Bertolini of Middlebury College spoke on Persuasion [see