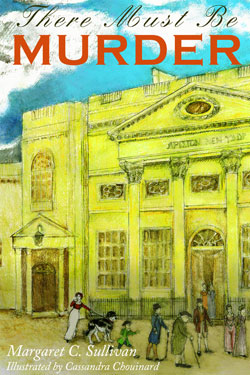

Book Giveaway! – see end of post for details

I love London – I had the fortune to spend a semester there in 1968 – the late 60s, a crazy invigorating time the likes the world has never seen again. When I started college, men and women were housed on opposite sides of the campus, by 1969, we were sharing dorms! I went to the London School of Economics to study political science, I, an English and sociology major – but there was one ‘political sociology’ course offered and more importantly the opportunity to finally visit the land where my parents were born. So I ended up scouring The Times every day and learning politcal theory [ugh!] and British legal history [fascinating] and researching race relations in 1968 Britain to fulfill my sociology requirement [wonderful but exhausting and depressing], but I was in London! I had all sorts of plans to meet Prince Charles [we are of an age!], and we did have sort of an encounter [another tale!]; but alas! it was not to be, and surely I am none the worse! – but I did meet my future husband on this abroad program – and thus began my ongoing love affair with England. Today I collect books about London and try to visit when I can [never often enough] and I think I might have finally gotten a handle on the London map and the squares and the history only to discover another alley, nook, or cranny yet to be discovered and studied.

My London collection suffers the fate of most collectors: not enough shelves to house the ones I have and certainly not enough for the potential stacks of London-related books – I started to limit my collecting to children’s books about or set in London, then started to just find materials about the late Georgian – Regency periods – still too many books – I have notebooks filled with bibliographic data and now engage in mad forays into google-books, which substantially helps my shelf problem as well as my pocketbook but not the fact that I love BOOKS!

A friend and I are giving a talk on Jane Austen’s London next month, so I have been pulling a lot of research together, reading some of those books I have on the shelf [and the floor!] and finding the myriad of information online – it is quite daunting really! But in this search I discovered that the Regency Romance author Louise Allen was publishing a short guide titled Walks Through Regency London – certainly a book I had to have… so hot off the presses it arrived, and it is quite the delight!

This is a book of walks, it is not a history of Regency London – for that you can spend an inordinate amount of quality time reading all those resources I mention above. What Ms. Allen has given us is a guide to walking around the prime areas of Regency London. The major drawback for me in trying to write this review is that I am the ultimate armchair traveler here, chained to my sofa [no fainting allowed] in snowbound Vermont trying to imagine trekking around these streets – how I wish I had this guide last February when I last visited Town! I took the Old Mayfair London Walks [1] tour, though I had been forewarned that it was not a literary-driven outing – What! I bellowed – no Jane Austen? No sneaking around the streets of Sense & Sensibility, looking for Willoughby or Edward, or Mrs. Jennings, or avoiding Fanny Dashwood if we should see her coming? No Jane Austen!? I cried! – “No Jane Austen” he said, clearly proud of eliminating her from the itinerary. It is great and instructive fun seeing the houses and imagining former inhabitants [thank that Blue Plaque program!], the architectural piece, but I wanted the “This is where Byron lived” (#8 St. James’s) and “This is where the Wedgwood had his showrooms”, and “This is where all the dancing took place at Almack’s.”

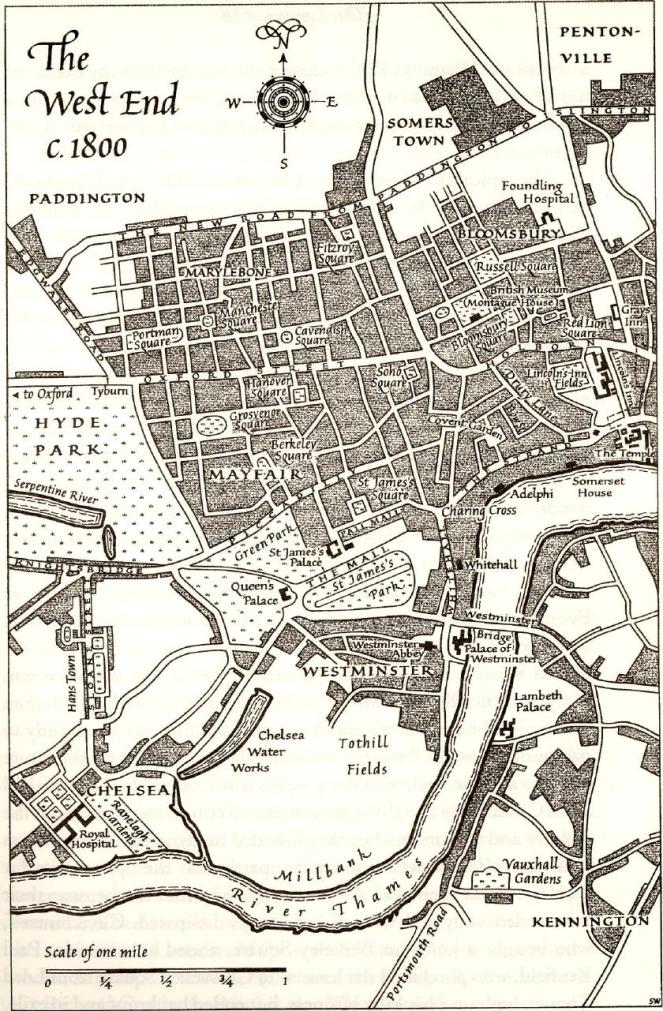

So how I wish I had this guide last year – it is the reason Louise wrote this book – her extensive Regency era research for her historical novels needed an outlet! And how hard the Regency is to pin down! – What was where when? When did that burn down? When was that demolished? Is that Victorian mansion camouflaging a Regency interior? Is this modern monstrosity on the plot of some famous building that Austen would have known and visited? One can get lost in their Horwood’s [2] trying to figure this all out – and even those maps changed so much over the several years of its editions, it could be a lifetime commitment to make sense of it all…

[Map image: The West End, c.1800. From Christopher Hibbert, London: The Biography of a City, 1969.]

In Walks Through Regency London, Louise tries to do just that, give substance to this very illusive nature of the Regency, as she says “fire, war and redevelopment have destroyed, changed and blurred the physical evidence of [the] past – yet it can still be found, sometimes intact, sometimes only as a ghost.” [Intro, p. i.] Walks is by no means a comprehensive guide – it is factual and anecdotal as you follow the directions on each tour: on this corner, such and such stood, this is where Wellington had his boots custom made; this is where Princess Caroline lived during her trial (# 17, now rebuilt), and Almack’s, now a new modern building at 26-8 King St, and this is where Frances Burney lived, etc … a mere 46 pages, but cram-packed!

I cannot verify all the data and comment on its reliability without doing the physical piece the guide is meant to accompany – one can read and follow along with a map [3], registering the endless details the guide provides, feeling the Regency come to life as you round each corner, filled with the buildings Jane Austen would have strolled by, made purchases in, as she likely took her own notes on where to place her characters in Sense & Sensibility so firmly (and proudly!) in Mayfair.

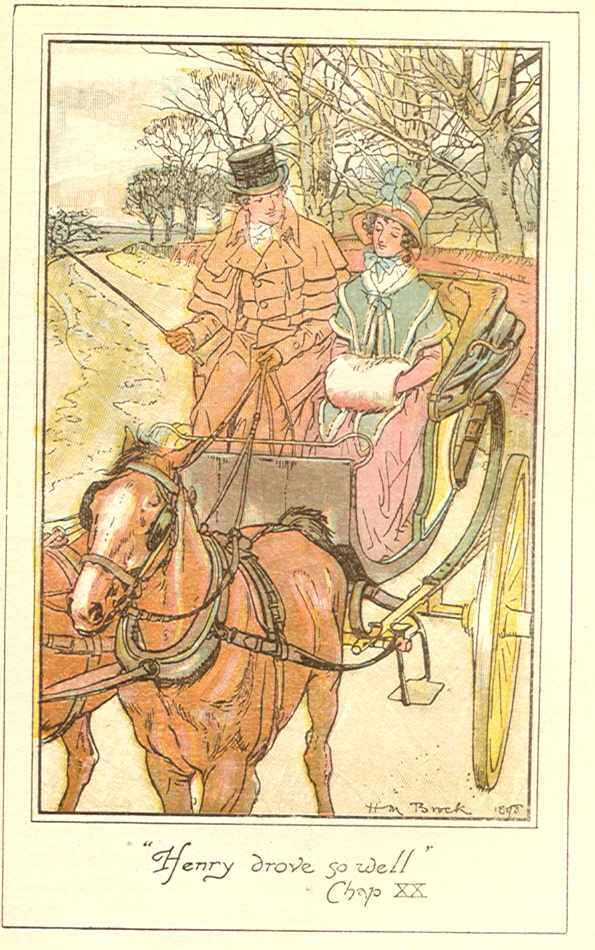

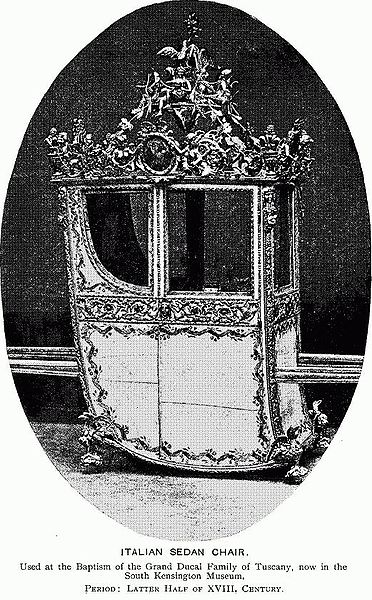

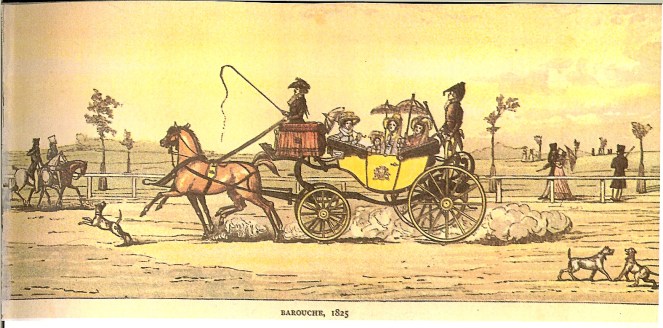

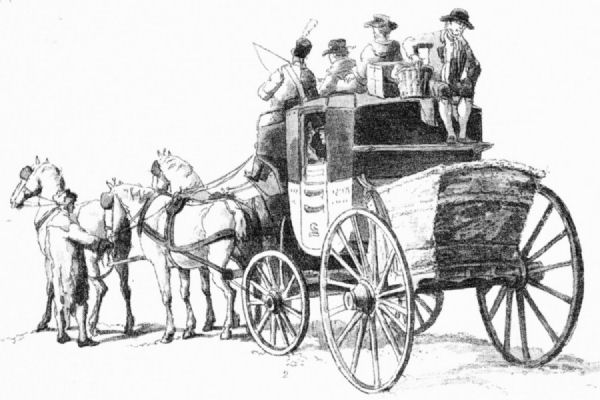

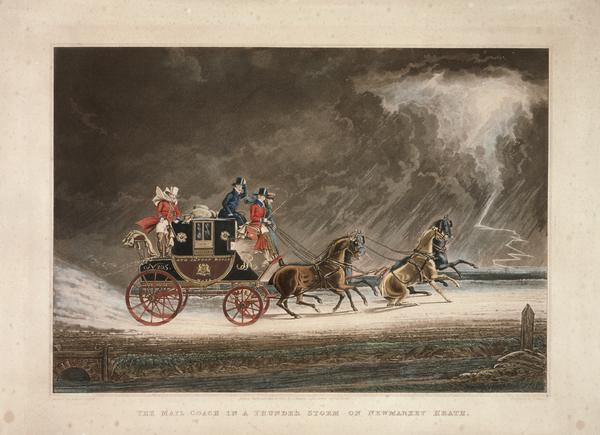

In her interview, Louise says she had enough material for twenty walks but chooses only ten (there are ten walks of about 2 miles each), and indeed, this is my only quibble [4] with the book! In its very compact 46 pages of quite small print, it all ends far too soon – I could have kept walking for at least another ten such tours! [easy to say from the sofa] – It is nicely presented with color illustrations from the author’s own print collection of London streets and fashions that set the scene; quotes from a contemporary source, the 1807 Picture of London (by John Feltham I believe, though this is not cited); walking directions; visiting information for public places (and sometimes a website); literary landmarks; shops, shops and more shops (so Regency!) – and add to this and Louise’s offering of the most interesting literary and historical tidbits and delicious gossip of the time and interspersed with commentary on what we see today.

Here are the ten walks:

- St. James’s

- Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens

- Mayfair North

- Piccadilly and South Mayfair

- Soho North

- Soho South to Somerset house

- British Museum to Covent Garden

- Trafalgar Square to Westminster

- The City from Bridewell to Bank

- Southwark and the South Bank

And here one short example from Walk 4: Piccadilly and South Mayfair where we happen to find Austen’s publisher John Murray:

Turn into the Royal Arcade, so through into Albemarle Street and turn left and walk down towards Piccadilly. (On Sundays go past the Arcade, turn left into Stafford Street and then left into Albemarle Street).

Virtually every literary ‘name’ of the 19th century must have come to Albemarle Street to visit the publisher John Murray. The firm moved to no. 50 in 1812 and has been there ever since. Amongst the greats, Murray published Jane Austen and Lord Byron, and, at Byron’s wish, burned his diaries after his death.

The street had at least three hotels in the Regency period including the Lothian and the Clarendon. The most famous was Grillon’s opposite John Murray’s. Louis XVIII stayed there in 1812 during the somewhat premature celebrations of Napoleon’s defeat.

Guests could have borrowed books from “Earle’s original French, English, Spanish and Italian circulating library … now moved to No, 47, Albemarle-street, Piccadilly, where all new books in the instructive and entertaining classes of literature are constantly added…”

Retrace your steps, turn left into Stafford Street to Dover Street and turn left.

Footnotes:

1. Note that London Walks does have a Jane Austen tour in their itinerary – when I was there, the guide was ill, so no Jane Austen for me that week! But I do not see it now on the schedule either – but I highly recommend these London Walks, where you can visit the haunts of Shakespeare and Dickens, Sherlock Holmes, the Inns of Court, Secret or Haunted London, and Greenwich, etc – it is all there for your to discover with their knowledgeable and entertaining guides.

2. For the most accessible access to the Horwood Map if you don’t have the Regency London A-Z book on your shelves, see the fabulous Regency Encyclopedia – you will need a password: JAScholar / Academia [case-sensitive] – click on Map Gallery and then Tour Regency London and then go exploring!

3. Ms. Allen says that “the book has been designed to not require a map. However, a standard tourist pocket map is helpful in locating tube stations and bus routes and in linking up walks. I use The Handy London Map and Guide by Bensons MapGuides. Otherwise all you need are a comfortable pair of shoes and an active imagination!” [p. i.]

4. quibble #2: a few spelling snafus: Cruickshank [should have no ‘c’] and Gilray [should have 2 ‘l’ s, though I believe it can also be spelled with one!] are both misspelled, but as Jane herself would likely overlook this, so alas! shall I!

4 1/2 full inkwells out of 5 ~ Highly recommended! … whether you are sitting in a chair or fortunate enough to have this guide as you meander around Town, you will enjoy the journey!

[Image from Nassau Library.org]

Your turn! – if anyone has any questions of Louise, please ask away! – see details for the book giveaway below… You can visit Louise’s website here and find her on Twitter @LouiseRegency

If you would like to order the Regency Walks book, you can do so directly from her website – I can attest to the book being mailed right away, arriving safe and sound and very quickly!

Book Giveaway: Please enter the drawing for a copy of Walks Through Regency London, compliments of ‘Jane Austen in Vermont’, by asking Louise a question or commenting on any of the three posts about this book. Drawing will take place next Wednesday 2 March 2011; comments accepted through 11 p.m. EST March 1st. [Delivery worldwide.]

Copyright @2011, Deb Barnum, at Jane Austen in Vermont.