We have looked at travel and the various carriages of the Regency Period in four previous posts. You can re-visit them here:

- Part I: Travel in Regency England

- Part II: A Study of Character’s Movement in S&S

- Part III: Travel S&S in Part III ~ The Carriages

- Part IV: Travel in S&S Part IV ~ The Carriages, cont’d

Now the fun part – on to the Regency sports cars! – those carriages that Austen assigns her young men and her rakes, those vehicles that Georgette Heyer made famous in her works, driven by all manner of her Regency bucks, and in many cases by her independent heroines. We start with the Phaeton, the last of the four-wheeled vehicles but much more stylish than the larger, practical coaches we have looked at previously…

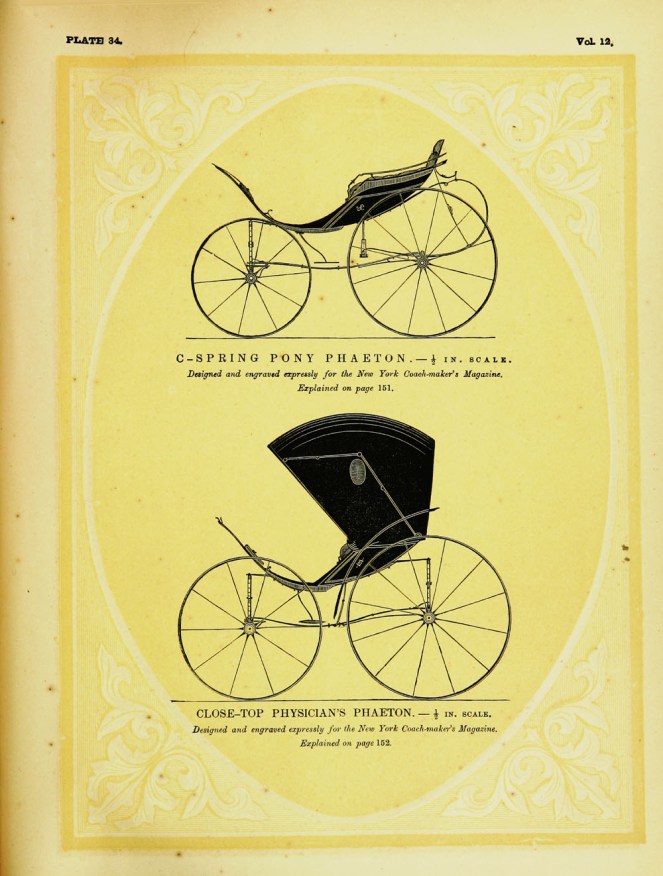

The Phaeton: termed “deliciously dangerous”

- from the Greek “to shine” – in Greek mythology, the boy who tried to drive the sun chariot

- a light 4-wheeled carriage with open sides in front of the seat; the front wheels were usually smaller that the rear

- sleigh-like single body, for two passengers, luggage below

- some had a folding top [a calash or callech = folding top] – a fair-weather carriage

- for pleasure driving, it is owner-driven with no box or postillion

- usually 1-2 horses or ponies

- the largest and most varied of all pleasure carriages, the phaeton remained popular until the end of the carriage era

- often called a “chaise” in England, a “cabriolet” in France

- variations: High-Perch Phaeton or “High-Flyer” – fast, sport driving with two horses – the favorite of the Prince Regent, later George IV who had six horses! – he used a low Phaeton after his weight increased to such a degree that he could not get into the high carriage!

- Who in Austen?: only Miss DeBourgh who has a pony phaeton; Mrs. Gardiner wants “a low phaeton with a nice little pair of ponies”

Two fashionable ladies in a “high-Perch Phaeton” driving about to see and “be seen”:

************

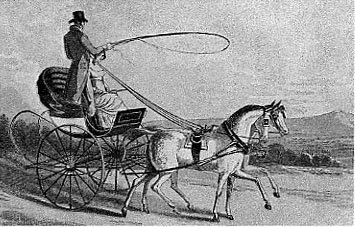

The Curricle: [only English] – the “Regency sports-car”

- name from the Latin: curriculum = running course, a (race) chariot

- a two-wheeled vehicle driven by a pair of horses that are perfectly matched, a bar across the back of the horses to carry the pole

- has a folding hood

- owner-driven, holds two passengers

- C-springs – after 1804, equipped with elliptical springs

- the popular Regency show-off vehicle – for long distances or park rides

- cost @ 100 pounds

A picture of the Marquis of Anglesey:

In Sense & Sensibility: Willoughby has a curricle though he cannot afford it:

-Willoughby on Colonel Brandon: “He has found fault with the hanging of my curricle…”

-Narrator on the carriage drives: …they might procure a tolerable composure of mind by driving about the country. The carriages were then ordered. Willoughby’s was first, and Marianne never looked happier that when she got into it. He drove through the park very fast, and they were soon out of sight; and nothing more of them was seen till their return, which did not happen till after the return of the rest. “Did not you know,” said Willoughby, “that we had been out in my curricle?”

[Willoughby to Mrs. Jennings]

-then later, Marianne explains the impropriety to Elinor: “We went in an open carriage, it was impossible to have any other companion.”

Who else in Austen? – Mr. Darcy, Henry Tilney [sigh!], Charles Musgrove, Walter Elliot, Mr. Rushworth, and Charles Hayter; and Austen’s brother Henry Austen [see Letter 84, where Henry drives Austen back to London in his “Curricle”].

**********

The Gig:

“Many young men who had chambers in the Temple made a very good appearance in the first circles and drove about town in very knowing gigs”

- Similar to the curricle, but more popular and economical; women could easily drive

- Two-wheeled, but pulled by one horse, two passengers, owner-driven

- Better suspension, easy to turn, more sophisticated than a chaise [often called a “one-horse chaise”]

- Had various names and modifications: the Dennet, Tilbury, Stanhope

- one common variation: a single seat behind the box for a groom, or a tiger

- cost: about 58 pounds

- Who else in Austen? the Crofts in Persuasion– they offer Anne a ride in their 2-passenger seat; Mr. Collins, Sir Edward Denham in Sanditon

-and of course, John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey, the most horse-obsessed character in all of English literature!

“I defy any man in England to make my horse go less than ten miles an hour in harness… look at his forehead; look at this loins; only see how he moves; that horse cannot go less than ten miles an hour: tie his legs and he will get on. What do you think of my gig, Miss Morland? a neat one, is not it? Well hung; town built; I have not had it a month… curricle hung you see; seat, trunk, sword-case, splashing boards, lamps, silver moulding, all you see complete; the iron-work as good as new, or better… etc. on and on!

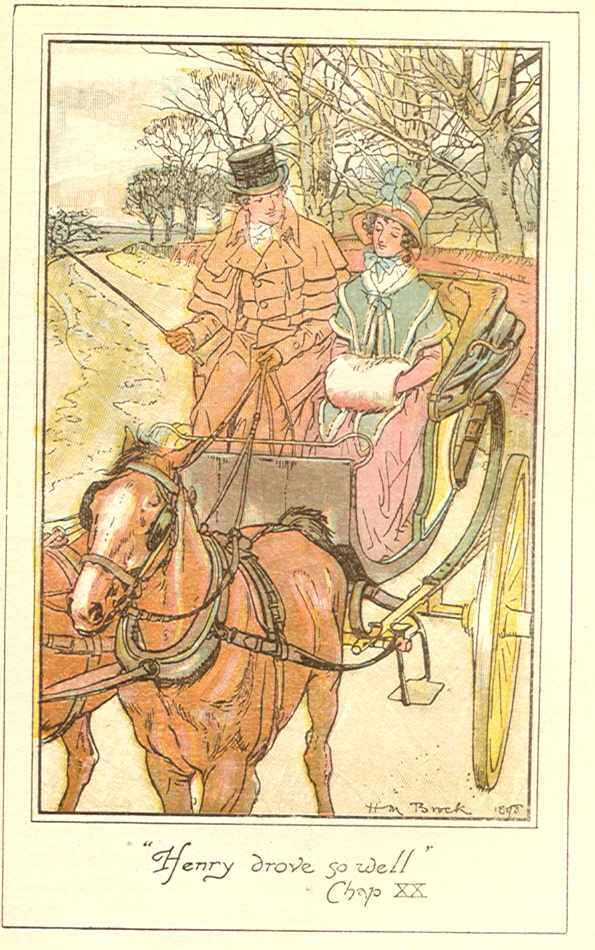

-And the Narrator who must have her say, so we know just how Catherine and the Narrator feel about John Thorpe [and Henry Tilney!]:

“A very short trial convinced her that a curricle was the prettiest equipage in the world…But the merit of the curricle did not all belong to the horses; – Henry drove so well, – so quietly – without making any disturbance, without parading to her, or swearing at them; so different from the only gentleman-coachman whom it was in her power to compare him with! – To be driven by him, next to being dancing with him, was certainly the greatest happiness in the world.”

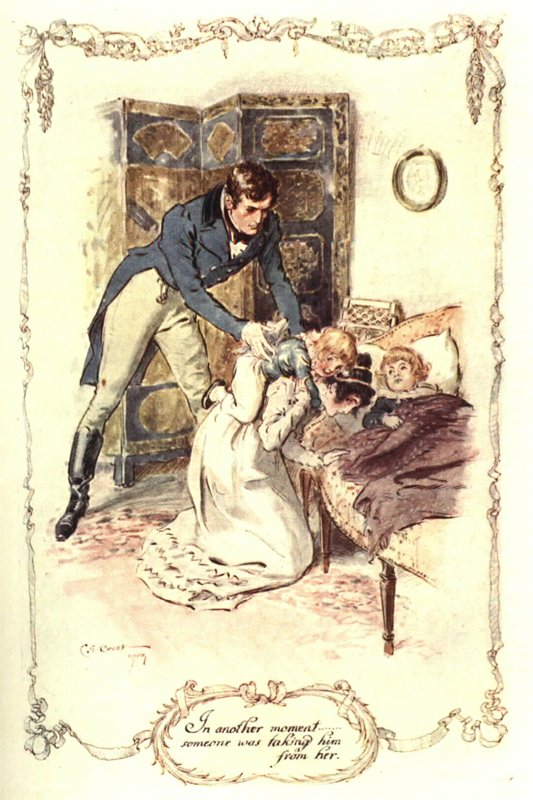

-the Narrator on Colonel Brandon when he leaves to get Mrs. Dashwood: “The horses arrived before they were expected, and Colonel Brandon…hurried into the carriage; it was then about twelve o’clock” [he returns the following day sometime after 8pm]

When Willoughby travels from London to Cleveland, a distance of about 124 miles, he is in a chaise with four horses, it takes 12 hours, 8am – 8pm, a trip that would normally take two days:

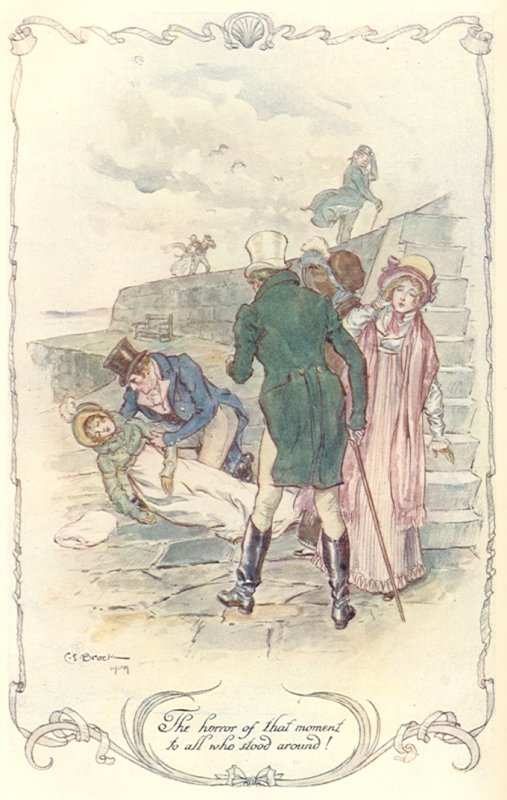

-the Narrator on Elinor: …she heard a carriage driving up to the house … the flaring lamps of a carriage were immediately in view. By their uncertain light she thought she could discern it to be drawn by four horses; and this, while it told the excess of her poor mother’s alarm, gave some explanation to such unexpected rapidity. – [and she runs downstairs to find it is Willoughby…!

******

Other Carriage terms: not all are found in Austen

- Hackney = for hire, often discarded carriages of the wealthy

- Dog Cart = a gig with a ventilated locker for dogs; for 4 people, 2 behind the driver seat back-to-back

- Sulky = driver-only – one passenger, one horse

- Tandem = a two-wheeled carriage drawn by 2 horses one in front of the other – Sidney Parker in Sanditon

- Whiskey or Chair – an early chaise; a light 2-wheeled vehicle without a top, in The Watsons

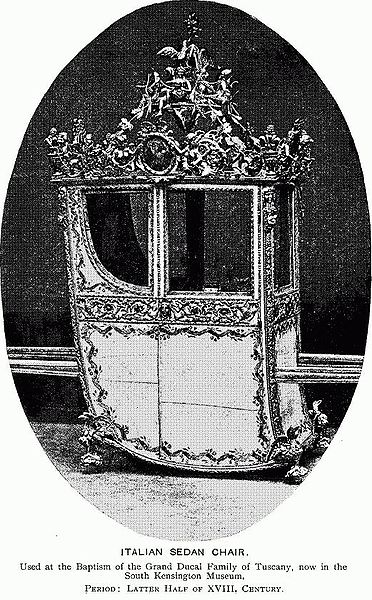

- Sedan-Chairs – a seat in a box with 2 poles 10-12 ft long, carried by two men. In efforts to lessen the crowded streets in London, but by 1821 there were only a half dozen public sedans, by 1830 there were none.

- “Britzochka” = German origin, most common of all carriages, for traveling [ called a “Brisker” or “Briskey”]

- “Droitzeschka” = “Drosky” – Russian origin, low to ground for “the aged, languid, nervous persons and children”

And finally, what did Jane Austen have?

- At Chawton she had a donkey cart

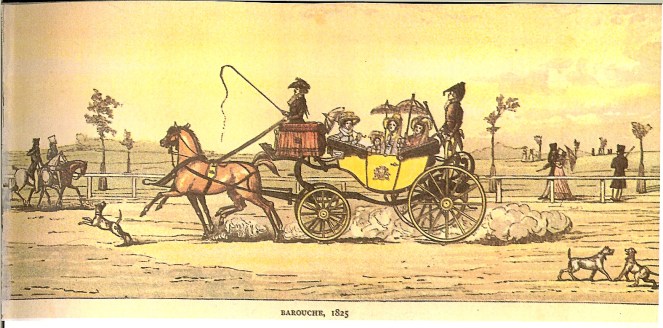

- Henry Austen had a curricle and a barouche:

“The Driving about, the Carriage [being] open, was very pleasant. – I liked my solitary elegance very much, & was ready to laugh all the time, at my being where I was. – I could not but feel that I had naturally small right to be parading about London in a Barouche.” [Ltr. 85, 24 May 1813, p. 213-14]

I love to think of Austen “parading” around London and enjoying her “solitary elegance” and laughing all the while! – one of my favorite passages from her letters…

Final post: a Carriages Bibliography ~ Stay tuned!

Copyright @ 2011, Deb Barnum, of Jane Austen in Vermont