I think I must be the only costume-drama-loving-female in all of America who did not see the 2004 (2005 USA) adaptation of Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South – where my head was that year I do not know – and add to that a further confession of never having read the book! – I am ashamed of myself! Can I have lived this long so in the dark? Are my English degrees so worthless in the light of this omission?

I have a good number of Gaskell’s books on my shelves, but there they sit awaiting that future day to begin my Gaskell immersion. But all this endless chatter on the airwaves [as well as a few friends imploring me to see the movie – largely a Richard Armitage thing…], I finally broke one of my cardinal rules – I saw the movie before reading the book. There were advantages of course to this sequence – every appearance of John Thornton on the page most pleasantly brought the absolutely lovely Mr. Armitage to mind – not a bad punishment for breaking this long-held rule of mine! – but I digress…

The story [for those of you more in the sand than me…] – Margaret Hale, a young woman from rural southern England [Austen’s Hampshire to be exact], daughter of a clergyman, proud of her roots and her class, must adjust to the changes in her life when her father resigns from his clerical post and moves the family to the northern industrial town of Milton [Gaskell’s fictitonalized Manchester]. Margaret gradually discovers her own strengths in taking on the many domestic duties of her now ill mother and those of their former servants. But Margaret carries with her the prejudices of the gentrified South with her “queenly” snobbish views of the industrial North and the manufacturers and tradesmen who run the mills. She is soon introduced to John Thornton, a self-made “Master” of one of the cotton mills and a local magistrate, well respected by his peers and his employees, yet aware of his shortcomings in the social and intellectual worlds outside of Milton. He comes to Reverend Hale for tutoring and intellectual stimulation – but it is Margaret who soon captures his heart, his passions aroused in spite of himself, all too sure of his own unworthiness in her eyes…

Margaret opened the door and went in with the straight, fearless, dignified presence habitual to her. She felt no awkwardness; she had too much the habits of society for that. Here was a person come on business to her father; and, as he was one who had shown himself obliging, she was disposed to treat him with a full measure of civility. Mr. Thornton was a good deal more surprised and discomfited than she. Instead of a quiet, middle-aged clergyman, a young lady came forward with frank dignity – a young lady of a different type to most of those he was in the habit of seeing. Her dress was very plain: a close straw bonnet of the best material and shape, trimmed with white ribbon; a dark silk gown, without any trimming or flounce; a large Indian shawl, which hung about her in long heavy folds, and which she wore as an empress wears her drapery. He did not understand who she was, as he caught the simple, straight, unabashed look, which showed that his being there was of no concern to the beautiful countenance, and called up no flush of surprise to the pale ivory of the complexion. He had heard that Mr. hale had a daughter, but he had imagined that she was a little girl … Mr. Thornton was in habits of authority himself, but she seemed to assume some kind of rule over him at once…. [p 72-3] He almost said to himself that he did not like her, before their conversation ended; he tried so to compensate himself for the mortified feeling, that while he looked upon her with an admiration he could not repress, she looked at him with proud indifference, taking him, he thought for what, in his irritation, he told himself he was – a great rough fellow, with not a grace or a refinement about him. Her quiet coldness of demeanour he interpreted into contemptuousness, and resented it is his heart … [p.74]

And Margaret’s view of Thornton:

“Oh! I hardly know what he is like,” said Margaret lazily; too tired to tax her powers of description much. And then rousing herself, she said, “He is a tall, broad-shouldered man, about- how old, papa?”… “About thirty, with a face that is neither exactly plain, nor yet handsome, nothing remarkable – not quite a gentleman; but that was hardly to be expected.”… “altogether a man who seems made for his niche, mamma; sagacious and strong, as becomes a great tradesman.”

Ahh! the pride and prejudices are set on each side, each thwarting their developing relationship – and a scenario not unlike Austen’s Pride & Prejudice unfolds. Margaret’s ingrained dislike of northern ways are gradually tempered by her sympathetic friendship with a family of mill workers and her growing appreciation for Thornton’s true nature; and Thornton’s own views of his employees and his responsibility to them are enlarged by Margaret’s very “democratic” views of an industrialized social system gone awry. It is a compelling read – [alert! there are some spoilers here ]–

Gaskell wrote North and South in 1854-5 – it appeared in serialized novel form in Dickens’s Household Words [Gaskell felt the ending was “unnatural” and “deformed” (1) – she added and edited for its publication as a book in 1855]. North and South is another of her works to focus on the social ills of the day – religious doubt; “Master” vs. hands and accompanying union struggles; male vs. female in the male-dominated industrial world; the responsibility of the owner / ruling classes to involve themselves in the lives of the less fortunate. But this novel has a more romantic telling than her previous works and perhaps why it remains one of her most enduring titles.. [ See my previous post on Gaskell for some background.]

And this comparison to Austen’s Pride & Prejudice cannot be ignored [just the title alone echoes Austen’s work] — Jenny Uglow in her introduction to the book (2) and in her fabulous biography of Gaskell (3) called North and South an “industrialized Pride & Prejudice,” “sexy, vivid and full of suspense” (4) – and indeed this states the case most eloquently. At last year’s JASNA AGM in Chicago on Austen’s legacy, Janine Barchas spoke on Gaskell’s North and South being the first of many Pride & Prejudice clones (5). The basic formula of P&P is what keeps people coming back for more, an annual re-read one of life’s many pleasures – and one can readily make a list of the similarities, all too clear despite Gaskell’s never making mention of her debt to Austen – this conflict of pride and prejudices, though often a gender reversal in Gaskell’s work [see Barchas’s article for a complete analysis of Margaret as Darcy and Thornton as Elizabeth], the awakening of their passions, and the emotional growth of Margaret and Thornton, the similarities in the secondary characters [Thornton’s sister Fanny is certainly as silly as Lydia; Mrs. Thornton’s visit to Margaret is almost a word for word Lady Catherine exhorting Elizabeth]; Thornton anonymously saving Margaret from a shameful exposure just as Darcy saves Elizabeth by forcing Wickham to do right by Lydia; and a final resolution of two people who finally overcome their own limited mindsets; and of course the turning point in both novels is the proposal scene, halfway through each book, the language similar, the devastating results the same.

But in Austen, who never felt comfortable with writing what she did not know, the mind of Darcy is never fully exposed to the reader [and the reason for the endless stream of sequels from Darcy’s point of view! – and also why the Andrew Davies adaptation with a glaring, agonized Colin Firth has such a strong hold on us all…] – but Gaskell was no prim Victorian in bringing the thoughts of Thornton to the page – he is clearly obsessed with Margaret from their first meeting noted above – and when he is visiting the Hales for tea, he focuses relentlessly on her arm and her bracelet:

She stood by the tea-table in a light-coloured muslin gown, which had a good deal of pink about it. She looked as if she was not attending to the conversation, but solely busy with the tea-cups, among which her round ivory hands moved with pretty, noiseless daintiness. She had a bracelet on one taper arm, which would fall down over her round wrist. Mr. Thornton watched the replacing of this troublesome ornament with far more attention that he listened to her father. It seemed as if it fascinated him to see her push it up impatiently until it tightened her soft flesh; and then to mark the loosening – the fall. He could almost have exclaimed – “there it goes again!” [p. 95]

Thornton watches her, listens to her, seeks her out, thinks of her all the time, and only when he believes he must protect her virtue does he express these pent-up feelings to her. Her rejection of him is devastating, though only unexpected because he believes she can do no less than submit to him – Gaskell clearly gives us a picture of a passionate, inconsolable man, almost beautiful in his agony – we do not need an Andrew Davies to draw this picture for us. It is as though Gaskell needed to put some finishing touches on the Darcy of our imaginations…

His heart throbbed loud and quick. Strong man as he was, he trembled at the anticipation of what he had to say, and how it might be received. She might droop, and flush, and flutter to his arms, as her natural home and resting-place. One moment he glowed with impatience at the thought that she might do this – the next he feared a passionate rejection, the very idea of which withered up his future with so deadly a blight that he refused to think of it…

He offers his love, she rejects him:

“Yes, I feel offended. You seem to fancy that my conduct of yesterday was a personal act between you and me; and that you come to thank me for it, instead of perceiving, as a gentleman would – yes! a gentleman,” she repeated….. – he says she does not understand him; she says “I do not care to understand” – [p.242-3] … and she afterward thinks, “how dared he say that he would love her still, even though she shook him off with contempt?” [p.245]

As only Hollywood [and the BBC] can do, there is the usual mucking about with the novel – a few changes [how they first meet, how they at last connect for starters!], deletions and insertions, a few character shifts, to make the movie more palatable to a contemporary audience – and though one can always quibble with the results of these probable midnight discussions [and I so often ask – WHY did they DO that? Why not just leave the book as it is, PLEASE!] – but that all aside, this movie is just lovely, no way around it… Daniela Denby-Ashe is a beautiful heroic and compassionate Margaret, and Richard Armitage SO perfect as John Thornton – he brings Thornton’s internal life so beautifully to the screen – it is a pitch-perfect performance [and the spring-board for his subsequent career – not to mention the Armitage online sites, the Facebook pages, YouTube concoctions, endless bloggings, women the world over in a communal swoon about this man!] [and alas! we ALL suffer for his NOT being the latest now-in-production Knightley incarnation…] Really, this all makes the 1995 Darcy-fever / Colin Firth insanity look like a kindergarten flirtation. I should just do an Armitage post with all the many links, pictures, readings – but I AM struggling here to stick to the book!

[but as an aside, if you haven’t seen Armitage as the evil Guy of Gisborne in BBC’s latest Robin Hood, get thee hence to your nearest video store and see the first two seasons now – there was never such fun in obsessing over the ultimate bad guy – a man just shouldn’t look and sound this lovely! – and after that, see The Impressionists [he is the young Monet], and then for a complete hoot see the last two shows of The Vicar of Dibley…] – but back to North and South [who can resist?], is there any scene in ANY movie to compare to “Look back – Look back at me” ?? !

[though even I have to admit it has to run a close second to Cary Grant in An Affair to Remember at his wrenching discovery of the painting in Deborah Kerr’s bedroom]…

But again, I digress! – Gaskell has given us a story similar to Pride & Prejudice in the basics, but set in the northern Victorian world she depicts so graphically – this is darker than Austen, without her language and ironic wit, there are certainly no Mr. Collinses around to give us needed comic relief [though on second thought, Fanny Thornton jumps right off the page as a very real self-absorbed very ridiculous girl and there are indeed many moments of humor] – this is a fabulous read, not easily forgotten with its powerful romance with its strong sexual tensions and the very real social issues of the time with such engaging characters in the lower class world of the mill workers. Read this book – then buy the movie [you will want to see it more than once!] – and thank you Richard Armitage for bringing me to this book in the most delightful roundabout way!

Notes and Further reading:

1. Uglow, Jenny. Elizabeth Gaskell: A Habit of Stories. NY: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1993, p. 368.

2. Gaskell, Elizabeth. North and South, with an introduction by Jenny Uglow. London: Vintage Books, 2008. [page numbers cited are to this edition]

3. Uglow, Jenny. 1993 biography.

4. Gaskell, Elizabeth. North and South, 2008 edition, p. xvi.

5. Barchas, Janine. “Mrs. Gaskell’s North and South: Austen’s Early Legacy.” Persuasions, No. 30, 2008, pp. 53-66.

Movies:

1. North and South, BBC 2004 [2005 USA] starring Daniela Denby-Ashe and Richard Armitage [see Imdb.com]

2. North and South, BBC 1975, starring Rosalie Shanks and Patrick Stewart [see Imdb.com]

Links: [a very select few to Gaskell, the book, the movie, and finally Richard Armitage, who indeed requires a post all his own…]

Gentle Readers: Maya Slater has penned a guest post for us on her book The Private Diary of Mr Darcy – and as I mention in my previous post, it is quite an entertaining read! Thank you Ms. Slater for sharing your thoughts with us [and those of Mr. Darcy!]

Gentle Readers: Maya Slater has penned a guest post for us on her book The Private Diary of Mr Darcy – and as I mention in my previous post, it is quite an entertaining read! Thank you Ms. Slater for sharing your thoughts with us [and those of Mr. Darcy!]

Julian Kestrel is back in this third Kate Ross mystery, Whom the Gods Love [Viking 1995], again faced with a murder the authorities cannot solve. The larger than life Alexander Falkland, one of the leaders of The Quality, young, handsome, with a beautiful wife, elegant home and many admirers, is found murdered in his study, bludgeoned with a fireplace poker during a house party. Falkland’s father, Sir Malcolm, so frustrated by the dead-end investigations of the Bow Street Runners, turns to Kestrel to find his son’s killer. Faced with a good number of suspects among family, friends and servants (so many in fact, that Ross prefaces the work with a listing of the cast of characters!), Kestrel falls whole-heartedly into his role as amateur sleuth. A dandified man of fashion [but we the reader know him to be so much more], Kestrel knows many of Falkland’s set and embarks on his questioning of all suspects in his charming way, all the while wondering if Alexander Falkland may not be all that he seems.

Julian Kestrel is back in this third Kate Ross mystery, Whom the Gods Love [Viking 1995], again faced with a murder the authorities cannot solve. The larger than life Alexander Falkland, one of the leaders of The Quality, young, handsome, with a beautiful wife, elegant home and many admirers, is found murdered in his study, bludgeoned with a fireplace poker during a house party. Falkland’s father, Sir Malcolm, so frustrated by the dead-end investigations of the Bow Street Runners, turns to Kestrel to find his son’s killer. Faced with a good number of suspects among family, friends and servants (so many in fact, that Ross prefaces the work with a listing of the cast of characters!), Kestrel falls whole-heartedly into his role as amateur sleuth. A dandified man of fashion [but we the reader know him to be so much more], Kestrel knows many of Falkland’s set and embarks on his questioning of all suspects in his charming way, all the while wondering if Alexander Falkland may not be all that he seems.

[Leah Hayes]

[Leah Hayes] A new approach to Jane Austen seemed impossible, but Susannah Fullerton . . . has brilliantly hit on the theme of crime and punishment in Austen. Fullerton shows how the Regency world . . . was really a dangerous place with a fast rising crime rate and a legal system that handed out ferocious sentences. Her book will be essential reading for every Janeite.”-Claire Tomalin, author of Jane Austen: A Life

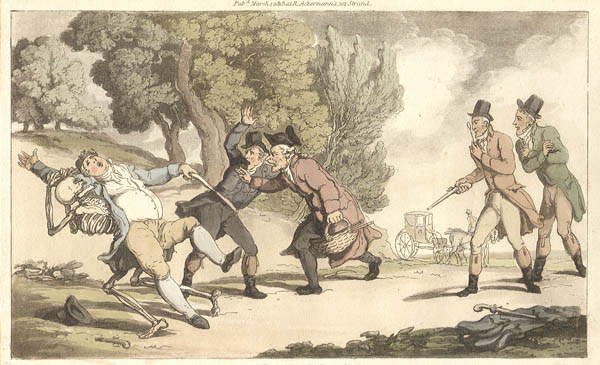

A new approach to Jane Austen seemed impossible, but Susannah Fullerton . . . has brilliantly hit on the theme of crime and punishment in Austen. Fullerton shows how the Regency world . . . was really a dangerous place with a fast rising crime rate and a legal system that handed out ferocious sentences. Her book will be essential reading for every Janeite.”-Claire Tomalin, author of Jane Austen: A Life![thomson-horsemen-crime The three villains in horsemen's greatcoats [Thomson, NA]](https://janeausteninvermont.blog/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/thomson-horsemen-crime.jpg?w=663) I most appreciated Fullerton’s many references to the juvenilia – it is in these works that Austen shows us the realities of her greater society, all indeed presented in an exaggerated manner with her youthful humor, but we do see how she understood this underside of life in both London and her country villages, a knowledge also apparent in the quick, short references in her letters. For instance, in this short passage from Letter 95 [Le Faye, p. 248], Austen writes her sister from Godmersham Park:

I most appreciated Fullerton’s many references to the juvenilia – it is in these works that Austen shows us the realities of her greater society, all indeed presented in an exaggerated manner with her youthful humor, but we do see how she understood this underside of life in both London and her country villages, a knowledge also apparent in the quick, short references in her letters. For instance, in this short passage from Letter 95 [Le Faye, p. 248], Austen writes her sister from Godmersham Park:

Julian Kestrel returns in this second mystery by Kate Ross [Viking 1994], A Broken Vessel. Several months after his amateur but superior sleuthing at Bellegarde, home of the Fontclairs, [see Ross’s first book, Cut to the Quick, and

Julian Kestrel returns in this second mystery by Kate Ross [Viking 1994], A Broken Vessel. Several months after his amateur but superior sleuthing at Bellegarde, home of the Fontclairs, [see Ross’s first book, Cut to the Quick, and