To be at the beginning of life, one must start at the end of the novel. For although Jane Austen concludes her books with the marriage of the hero and heroine to which the whole thrust of the narrative has been leading, and the reader rejoices in the perfect happiness of the union, in reality the best is yet to come: they will have children – procreation being not only the natural and desirable end of marriage, but also an economic and dynastic necessity. And those children will have their own stories…What will become of the Darcy children?…” (Ch. 1, Confinement, p. 5)

To be at the beginning of life, one must start at the end of the novel. For although Jane Austen concludes her books with the marriage of the hero and heroine to which the whole thrust of the narrative has been leading, and the reader rejoices in the perfect happiness of the union, in reality the best is yet to come: they will have children – procreation being not only the natural and desirable end of marriage, but also an economic and dynastic necessity. And those children will have their own stories…What will become of the Darcy children?…” (Ch. 1, Confinement, p. 5)

And thus does David Selwyn begin his treatise on Jane Austen and Children (Continuum, 2010), a most enjoyable journey through the world of childhood and parenting and education and growing-up in the life of Jane Austen, and the lives of her fictional characters. If you are perhaps one of those people who think that Jane Austen does not like children, an idea certainly fed buy such comments about women “breeding again” or the child-generated “dirt and noise” or “the two parties of Children is the cheif Evil” [Ltr. 92], or the proper child-rearing “Method has been wanting” [Ltr. 86], etc. – you need to read this book!

Selwyn takes his reader essentially through the nine ages of man [with apologies to Shakespeare] beginning with confinement and birth, through infancy, childhood, parenting, sibling relations, reading and education, and finally maturity, as Selwyn says, the “end of the novel” when the Hero and Heroine come together, after all manner of trial and tribulation, to begin their own family.

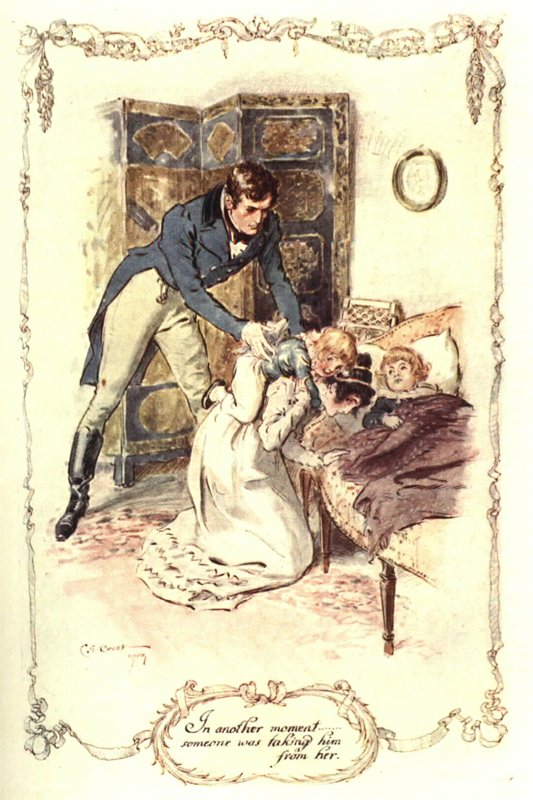

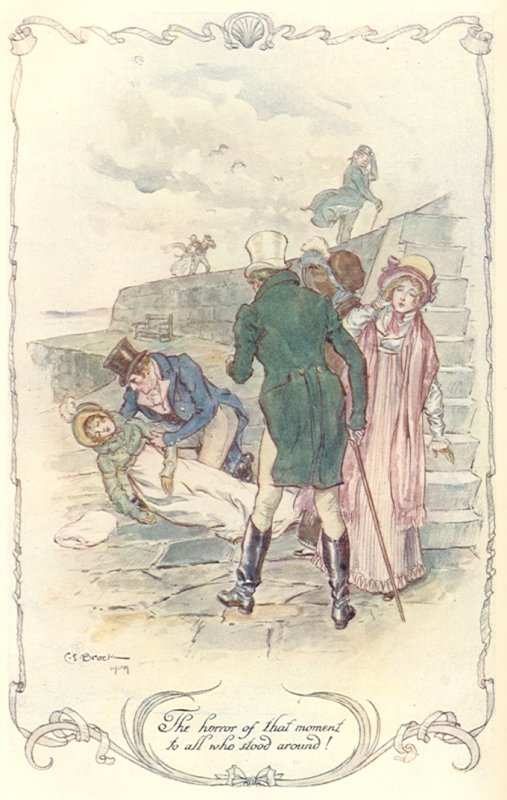

We are given a general survey of the shift in the attitudes toward children, that late eighteenth – early nineteenth century view that fell between viewing children as not just “little adults” to the Victorian view of “seen but not heard”, following Locke and Rousseau and believing children to be natural innocents. In each chapter Selwyn seamlessly weaves pieces of Austen’s life as gleaned from her letters and scenes from all her writings – and it is masterly done, all with a historical perspective. We see Jane as a child, as a madly composing adolescent, a loving and humorous Aunt imaginatively interacting with her nieces and nephews, and as an accomplished writer whose fictional children are far more worthy of our notice than we have previously supposed: the frolicsome Walter hanging on Anne’s neck in Persuasion; the spoiled Middletons; the noisy and undisciplined Musgroves; the grateful and engaging Charles Blake in The Watsons; the John Knightley brood in the air courtesy of their Uncle George; the dynamics of the five Bennet sisters; Henry Dashwood the center of attention for the manipulative Steele sisters; the reality-based scenes of Betsy and Susan Price at Portsmouth; and finally Fanny Price, Austen’s only heroine we see grow up from childhood, having an elegant come-out, finding true-live and ends “needing a larger home.”

In all her works, Austen uses children as “a resource for her narrative strategies” (p. 4), be that comedy, a plot device to further the action, or a means of revealing attitudes and responses of the adults around them (p. 3). Austen’s children are easy to miss – they won’t be after reading this book – here they are brought to life, given character and meaning, and you will see what Selwyn terms “Austen’s satirical delight in children behaving in character” (p. 73)

If Austen’s fiction seems to gloss over the reality of childbirth [the exception is Sense and Sensibility’s two Elizas], her letters tell the tale of its dangers [Austen lost three sisters-in-law to death in childbirth], and Selwyn links all to the social structure of the day, the nursing of babies and swaddling practices, to child rearing theories and moralizing tracts, and governesses and Austen’s ambivalence toward them. We visit boarding schools along with Jane and her characters and we hear the voices of a number of contemporary diarists (Agnes Porter, Sophia Baker, Susan Sibbald, Elizabeth Ham and Sarah Pennington). There is a lovely in-depth chapter on the reading materials written especially for children and Austen’s first-hand knowledge of these titles. The discussion on sisters and brothers, those so important in Austen’s own life, and those in her fiction, for example, characters with confidants (Lizzy and Jane, Elinor and Marianne), those isolated (Fanny, Anne Elliot, Emma Watson, Mary Bennet), and those with younger sisters (Margaret Dashwood and Susan Price). As part of the growing-up process, Selwyn uncovers much on “coming-out” as Austen herself writes of in her “Collection of Letters” [available online here] – with the emphasis here on Fanny as the only heroine to have a detailed “coming-out” party.

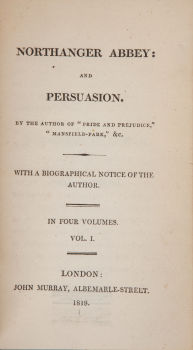

The chapter on “Parents” starts with the premise that “in Jane Austen’s novels the parents best suited to bringing up children are dead” (p.95) and Selwyn takes us from the historical view of parenting, through Dr. Johnson’s “Cruelty of Parental Tyranny” [shadows of Northanger Abbey] to a full discussion of the marriage debate in the 18th-century – that between the worldly concerns of wealth vs. choice of partner based on emotional love as personified in Sir Thomas and Fanny Price respectively. Excerpts are included from James Austen’s very humorous Loiterer piece “The Absurdity of Marrying from Affection.” (p. 207) and Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to his Daughters (1774) [viewable at Google Books here] , and the Edgeworth’s Practical Education (1798) [Vol. III at Google Books here]. One finds that in reading all of Austen’s letters and all the works you can indeed discover a complete instruction manual for good parenting!

Jane Austen and Children appropriately ends with Selwyn’s speculation on what sort of parents her Heroes and Heroines will be, all of course based on the subtle and not-so-subtle clues that Austen has given us throughout each work – conjecturing on this is perhaps why we have so many sequels with little Darcys, Brandons, Bertrams, Knightleys, Tilneys, and Ferrars running about!

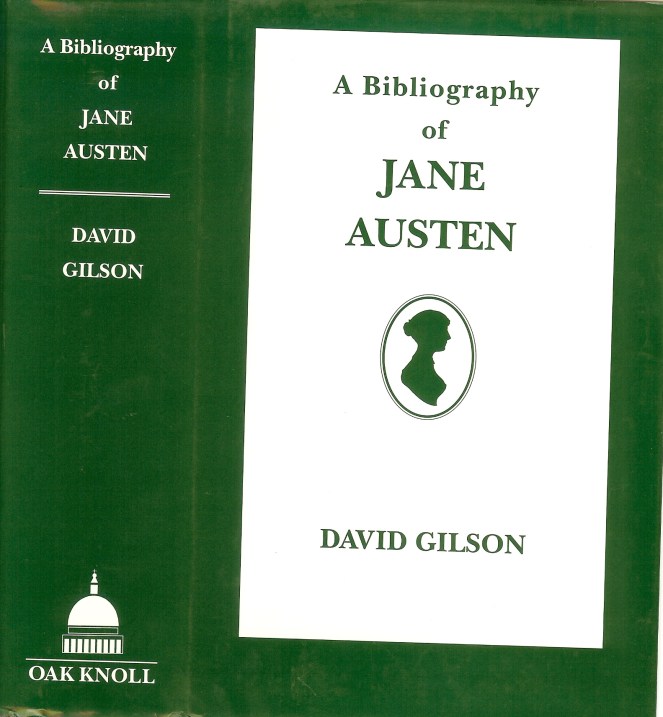

Just as in his Jane Austen and Leisure, where Selwyn analyzes the various intellectual, domestic and social pursuits of the gentry as evidenced in Austen’s world and her works, he here gives us an accessible and delightful treatise on Austen’s children, culling from her works the many quotes and references related to children and linking all to the historical context of the place of children in the long eighteenth century. The book has extensive notes, a fine bibliography of sources on child-rearing, contemporary primary materials, children’s literature, and literary history, and several black and white illustrations. (I did note that there are a few mixed up footnotes in chapter 3, hopefully to be corrected in the next printing). What will this book give you? – you will never again miss the importance of Austen’s many children, peaking from behind the page, there for a set purpose to show you what great parents the Gardners are, or just to make certain you see how very selfish the John Dashwoods and the Miss Steeles are, or to see the generosity of an Emma Watson in her rescue of Charles Blake, or to feel the lack for the poor Musgrove boys having Mary for a mother, the playfulness of an otherwise conservative Mr. Knightley, and the unnerving near touch of Captain Wentworth as he relieves Anne of her burden – thank you David Selwyn for bringing all these children to life for Austen’s many readers – you have given us all a gift!

Emma – ‘Tosses them up to the ceiling’

[by Hugh Thomson, print at Solitary Elegance]

__________________

Jane Austen and Children

Continuum, 2010

ISBN: 978-1847-250414

David Selwyn is a teacher at the Bristol School in Bristol, UK. He has been involved with the Jane Austen Society [UK] for a number of years, has been the Chairman since 2008, the editor of the JAS Report since 2001, and has written and edited several works on Austen. He very graciously agreed to an “interview” about this latest work that you can find by clicking here. See also the post on the various illustrations of Austen’s children by the Brocks and Hugh Thomson. And finally, I append below a select bibliography of Selwyn’s writings on Jane Austen and her family.

Select Bibliography:

- Lane, Maggie, and David Selwyn, eds. Jane Austen: A Celebration. Manchester: Fyfield, 2000.

- Selwyn, David, ed. The Complete Poems of James Austen, Jane Austen’s Eldest Brother. Chawton: Jane Austen Society, 2003.

- _____. “Consumer Goods.” Jane Austen in Context. Ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge Ed. of the Works of Jane Austen. New York: Cambridge UP, 2005. 215-24.

- _____, ed. Fugitive Pieces: Trifles Light as Air: The Poems of James Edward Austen-Leigh. Winchester: Jane Austen Society, 2006.

- _____. “A Funeral at Bray, 1876.” Jane Austen Society, Collected Reports V (1998): 480-86.

- _____. “Games and Play in Jane Austen’s Literary Structures.” Persuasions 23: 15-28

- _____. “Incidental closures in Mansfield Park.” [Conference on “Jane Austen and Endings”, University of London, 17 November 2007] – unpublished paper.

- _____. “James Austen – Artist.” Jane Austen Society Report 1998. 157-63.

- _____. Jane Austen and Leisure. London: Hambledon Continuum, 1999.

- _____, ed. Jane Austen: Collected poems and Verse of the Austen Family. Manchester: Carcanet / Jane Austen Society, 1996.

- _____, ed. Jane Austen Society Report, 2001 – present.

- _____. “Poetry.” Jane Austen in Context. Ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge Ed. of the Works of Jane Austen. New York: Cambridge UP, 2005. 59-67.

- _____. “Shades of the Austens’ Friends.” Jane Austen Society Collected Reports V (2002): 134.

- _____. “Some Sermons of Mr Austen.” Jane Austen Society Collected Reports V (2001): 37-38.

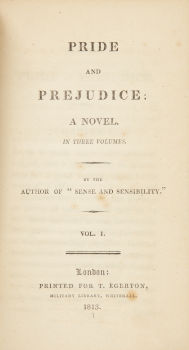

Many of us who grew up in the late 40s – early 50s had our Jane Austen force-fed to us in high school (unless we were fortunate enough to be blessed with an Austen-loving mother or father!). Pride & Prejudice was the standard text with little reference to the other works; followed by George Eliot’s Silas Marner, Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities and / or Great Expectations, Shakespeare (hopefully!), and Hemingway, Steinbeck, Salinger for contemporary authors. But I’ve often thought that Austen got a bum-rap with this “required-reading” status, the educational system’s way of compensating for what an early critic said in calling Austen “a critic’s novelist – highly spoken of and little read.” [p. 120] And while I am the first to admit that Austen is not for everyone [their terrible loss!], I have long believed that this approach to Austen added to her suffering from the great reader-turnoff.

Many of us who grew up in the late 40s – early 50s had our Jane Austen force-fed to us in high school (unless we were fortunate enough to be blessed with an Austen-loving mother or father!). Pride & Prejudice was the standard text with little reference to the other works; followed by George Eliot’s Silas Marner, Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities and / or Great Expectations, Shakespeare (hopefully!), and Hemingway, Steinbeck, Salinger for contemporary authors. But I’ve often thought that Austen got a bum-rap with this “required-reading” status, the educational system’s way of compensating for what an early critic said in calling Austen “a critic’s novelist – highly spoken of and little read.” [p. 120] And while I am the first to admit that Austen is not for everyone [their terrible loss!], I have long believed that this approach to Austen added to her suffering from the great reader-turnoff.