Welcome to the 14th stop on today’s celebration of Elizabeth Gaskell’s birthday – September 29, 1810! Please join me in this blog tour honoring Gaskell as 15 bloggers, under the direction of Laurel Ann at Austenprose, each post something related to Gaskell – a look at her life and times, book reviews, movie reviews, a tour to her home in Manchester [see at the bottom of this post for the links to the various posts on the blog tour], and my post on “Your Gaskell Library” ~ where to find Gaskell in print, online, on your iPhone, on your iPod, and on film – she is Everywhere! By the end of the tour you will know more about Gaskell than you thought possible and be the better for it!! There is also the opportunity to win a Naxos recording of North and South by just making a comment on any of the blogs. Enjoy yourself as we all wish a hearty Happy Birthday to Mrs. Gaskell!

********************

I wanted to see the place where Margaret grew to what she is,

even at the worst time of all,

when I had no hope of ever calling her mine…

North and South

*************

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (1810-1865) is best known to us as the author of the then-controversial biography of Charlotte Bronte, where she laid bare the oddities of the Bronte household, publicizing the behavior of the semi-mad father and the destructive life and affairs of the son. But Gaskell was a well-respected and popular author in her own day; we have been seeing a resurgence of that popularity with the broadcast of Wives & Daughters (1999), North & South (2004) [the film that rocketed Richard Armitage to fame, and rightly so!], and Cranford (2007, 2009). So I give a very brief review of her life and works [this was originally posted here], followed by a select bibliography.

Born in Cheshire to William Stevenson, a Unitarian minister, Elizabeth was raised by her aunt, the sister of her mother who died shortly after her birth. The town of Knutsford and the country life she experienced there became her setting in Cranford and her “Hollingford” in North & South. She married William Gaskell of Manchester, also a Unitarian minister, in 1832, had four daughters and one son, who died in infancy. The loss of her son had a devastating effect on her and to keep herself from sinking into an ever-deeper depression, she took pen in hand and started to write. She published her first book Mary Barton in 1848 (using the pseudonym Cotton Mather Mills), though there is some speculation that she actually started to write Sylvia’s Lovers (1863) first but put it aside to write the more socially conscious Mary Barton. Gaskell, according to Lucy Stebbins, was chiefly concerned with the ethical question of ”The Lie”, i.e. a belief that “deception was the greatest obstacle to the sympathetic understanding which was her panacea for individual and class quarrels.” (1) This reconciliation between individuals of different classes and between the wider world of masters and workers was her hope for humanity and it was this zeal that often led her into false sentiment in her novels and stories.(2) But because she saw both sides of the labor question and pitied both the oppressor and the oppressed, she was thus able to portray with often explicit candor the realities of her world. But Stebbins also says that life was too kind to her as a woman to make her a great artist. Her tales of vengeance and remorse were written more to satisfy public taste, after she started publishing in Dickens’ Household Words. And David Cecil calls Gaskell “a typical Victorian woman….a wife and mother”….he emphasizes her femininity, which he says gives her the strengths of her detail and a “freshness of outlook” in her portrayals of the country gentry, while at the same time this femininity limits her imagination. In comparing her to Jane Austen, Cecil writes:

It is true Mrs. Gaskell lived a narrow life, but Jane Austen, living a life just as narrow, was able to make works of major art out of it. Jane Austen…was a woman of very abnormal penetration and intensity of genius. ….. [Gaskell] cannot, as Jane Austen did, make one little room an everywhere; pierce through the surface facts of a village tea-party to reveal the universal laws of human conduct that they illustrate. If she [Gaskell] writes about a village tea-party, it is just a village tea-party…(3)

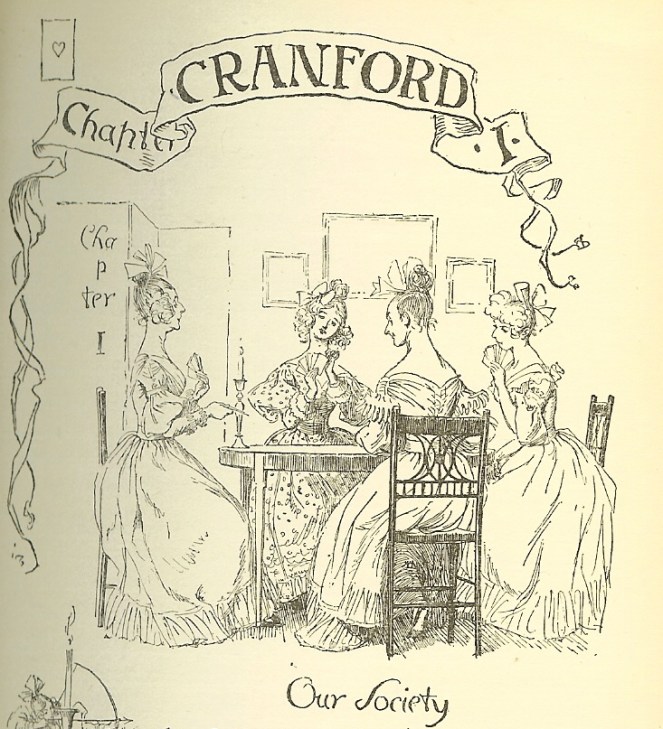

Cecil is critical of her melodrama, her “weakness for a happy ending”, her overlong works that lack imagination and passion. But he does credit her four major works (Sylvia’s Lovers, Cranford, Wives & Daughters, and Cousin Phillis) as classic and worthy English domestic novels.

[Cranford, illustrated by Hugh Thomson. London : Macmillan, 1891..

This copy is also available at the Illustrated Cranford site. ]

Anne Thackeray Ritchie, in her introduction to Cranford, published in 1891, also compares Gaskell to Austen, and finds the latter lacking:

Cranford is farther removed from the world, and yet more attuned to its larger interests than Meryton or Kellynch or Hartfield….Drumble, the great noisy manufacturing town, is its metropolis, not Bath with its successions of card parties and Assembly Rooms.” …. and on love, “there is more real feeling in these few signs of what once was, than in all the Misses Bennett’s youthful romances put together…only Miss Austen’s very sweetest heroines (including her own irresistible dark-eyed self, in her big cap and faded kerchief) are worthy of this old place….” and later, “it was because she had written Mary Barton that some deeper echoes reach us in Cranford than are to be found in any of Jane Austen’s books, delightful though they be. (4)

Margaret Lane in her wonderful book of essays on biography, Purely for Pleasure [which also includes the essay “Jane Austen’s Sleight-of-hand”], has two essays on Mrs. Gaskell. Lane calls her one of the greatest novelists of the time, and especially praises Wives & Daughters over Cranford for its stature, sympathies, mature grasp of character and its humour, and its effect of “creating the illusion of a return to a more rigid but also more stable and innocent world than ours” and we feel refreshed in spirit after a reading. (5)

Wives & Daughters, Gaskell’s last work, and considered her finest, was published as a serial novel in Cornhill, the last unfinished part appearing in January 1866. Gaskell had literally dropped dead in the middle of a spoken sentence at the age of 55, and the work remained unfinished, with only a long note from the Cornhill editor following the last serial installment. Wives and Daughters tells the story of Molly Gibson and her new stepsister Cynthia, and their coming of age in the male-dominated mid-Victorian society of “Hollingford.”

But it is Lane’s essay on “Mrs. Gaskell’s Task” in which she so highly praises Gaskell’s achievement in her biography of Charlotte Bronte. While Gaskell obviously suppressed some facts (the letters to M. Heger) and exaggerated others (Mr. Bronte as a father and Branwell as a son), Lane says “her great biography remains a stirring and noble work, one of the first in our language…. and it is in essence ‘truer’ than anything about the Brontes which has been written since…”(6)

Such contrary opinions!…certainly reminiscent of Austen’s admirers and critics! Perhaps as Pam Morris says in her introduction to W&D, “Gaskell resists any simple categorization…her work ranges across the narrative forms of realism and fairytale, protest fiction and pastoralism, melodrama and the domestic novel.”(7)

_______________________________________

_______________________________________

Notes:

1. Lucy Poate Stebbins. A Victorian Album: Some lady Novelists of the Period (Columbia, 1946) p. 96.

2. Ibid.

3. David Cecil. Victorian Novelists: Essays in Revaluation (Chicago, 1962) p. 187.

4. Anne Thackeray Ritchie. Preface to Cranford (Macmillan, 1927) pp. vii, xix.

5. Margaret Lane. Purely for Pleasure (Hamish Hamilton, 1966) p. 153.

6. Ibid, p. 170.

7. Pam Morris. Introduction to Wives and Daughters (Penguin, 2001) p. vii.

*****************

I append below a “Select Bibliography” of Gaskell’s works, biographies and critical works, as well as links to what can be found online, iPhone, audio, and film – and most everything Gaskell wrote IS available. Many of her writings were originally published in the periodicals of the day, such as Howitt’s Journal, Sartain’s Union Magazine, Harper’s Monthly Magazine, Dickens’s Household Words and All the Year Round, and Cornhill Magazine; and many of these writings were later published in collections of tales. And, like Dickens, some of her novels were originally published in serial form [Cranford, North and South, Wives and Daughters]. I list below the novels as first published in book form, a list of short stories and essays with date of original appearance in print, and a list of current editions you can find in your local bookstore [I list only the Oxford, Penguin and Broadview editions – there are many others and reprints of all kinds – best to look for an edition with a good introduction and notes.] There is a lot of information here, with links to even more information available on the web – there is no lack of writing on Mrs. Gaskell! – But what I really want to emphasize are her short stories, which often get lost in the hoopla about her major novels – there are many as you will see, with links appended – try some – you will not be disappointed!

****************************

Bibliography: Selected list [see links below for more complete bibliographies]

Works: Books, Short Story Collections

- Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life. 2 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1848; 1 volume, New York: Harper, 1848.

- Libbie Marsh’s Three Eras: A Lancashire Tale. London: Hamilton, Adams, 1850.

- The Moorland Cottage. London: Chapman & Hall, 1850; New York: Harper, 1851.

- Ruth: A Novel. 3 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1853; 1 volume, Boston: Ticknor, Reed & Fields, 1853.

- Cranford. London: Chapman & Hall, 1853; New York: Harper, 1853.

- Hand and Heart; and Bessy’s Troubles at Home. London: Chapman and Hall, 1855.

- Lizzie Leigh and Other Tales. London: Chapman & Hall, 1855; Philadelphia: Hardy, 1869.

- North and South. 2 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1855; 1 vol., New York: Harper, 1855.

- The Life of Charlotte Brontë; Author of “Jane Eyre,” “Shirley,” “Villette” etc.. 2 vols. London: Smith, Elder, 1857; New York: Appleton, 1857.

- My Lady Ludlow, A Novel. New York: Harper, 1858; republished as Round the Sofa. 2 vols. London: Low, 1859.

- Right at Last, and Other Tales. London: Low, 1860; New York: Harper, 1860.

- Lois the Witch and Other Tales. Leipzig: Tauchnitz 1861.

- Sylvia’s Lovers. 3 vols. London: Smith, Elder, 1863; 1 vol. New York: Dutton, 1863.

- A Dark Night’s Work. London: Smith, Elder, 1863; New York: Harper, 1863.

- Cousin Phillis: A Tale. New York: Harper, 1864; republished as Cousin Phillis and Other Tales. London: Smith, Elder, 1865.

- The Grey Woman and Other Tales. London: Smith, Elder, 1865; New York: Harper, 1882.

- Wives and Daughters: An Every-Day Story. 2 vols. London: Smith, Elder, 1866; 1 vol., New York: Harper, 1866.

Works: Short Stories and Essays [in order of publication] – most of these are available online at The Gaskell Web, Project Gutenberg, IPhone (Stanza – Munsey’s), etc.

- On Visiting the Grave of my Stillborn Little Girl (1837)

- Sketches Among the Poor, No.1 (1837)

- Notes on Cheshire Customs (1839)

- Description of Clopton Hall (1840)

- Life In Manchester: Libbie Marsh’s Three Eras (1847)

- The Sexton’s hero (1847)

- Emerson’s lectures (1847) [attributed]

- Christmas Storms and Sunshine (1848)

- Hand and Heart (1849)

- The Last Generation in England (1849)

- Martha Preston (1850) – re-written as “Half a Lifetime Ago”

- Lizzie Leigh (1850)

- The Well of Pen-Morfa (1850)

- The Heart of John Middleton (1850)

- Mr. Harrison’s Confessions (1851)

- Disappearances (1851)

- Our Society in Cranford (1851)

- A Love Affair at Cranford (1852)

- Bessy’s Troubles at Home (1852)

- Memory at Cranford (1852)

- Visiting at Cranford (1852)

- The Shah’s English Gardener (1852)

- The Old Nurse’s Story (1852)

- Cumberland Sheep Shearers (1853)

- The Great Cranford Panic (1853)

- Stopped Payment at Cranford (1853)

- Friends in Need (1853)

- A Happy Return to Cranford (1853)

- Bran (1853)

- Morton Hall (1853)

- Traits and Stories of the Huguenots (1853)

- My French Master (1853)

- The Squire’s Story (1853)

- The Scholar’s Story (1853)

- Uncle Peter (1853)

- Modern Greek Songs (1854)

- Company Manners (1854)

- An Accursed race (1855)

- Half a lifetime Ago (1855) [see above “Martha Preston”]

- The Poor Clare (1856)

- The Siege of the Black Cottage (1857) – attributed

- Preface to Maria Susanna Cummins Mabel Vaughan (1857)

- The Doom of the Griffiths (1858)

- An Incident at Niagara Falls (1858)

- The Sin of a Father (1858) – re-titled Right at Last in collection

- The Manchester Marriage (1858)

- The Half-Brothers (1859) – in Round the Sofa collection

- Lois the Witch (1859)

- The Ghost in the Garden Room (1859) – re-titled “The Crooked Branch” in Right at Last collection

- Curious if True (1860)

- The Grey Woman (1861)

- Preface to C. Augusto Vecchi, Garibladi at Caprera (1862)

- Six Weeks at Heppenheim (1862)

- Shams (1863)

- An Italian Institution (1863)

- The Cage at Cranford (18863)

- Obituary of Robert Gould Shaw (1863)

- How the First Floor Went to Crowley Castle (1863)

- French Life (1864)

- Some Passages from the History of the Chomley Family (1864)

- Columns of Gossip from Paris (1865)

- A Parson’s Holiday (1865)

- Two Fragments of Ghost Stories [n.d]

Works ~ Collections:

- The Works of Mrs. Gaskell, Knutsford Edition, edited by A. W. Ward. 8 vols. London: Smith, Elder, 1906-1911.

- The Novels and Tales of Mrs. Gaskell, edited by C. K. Shorter. 11 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1906-1919.

- The Works of Elizabeth Gaskell, ed. Joanne Shattuck, et.al. 10 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2005-2006. Click here for more info on this set.

Currently in print ~ Individual Works and Collections: [only the Penguin, Oxford and Broadview Press editions are noted here – there are a number of available editions of Gaskell’s individual works – search on Abebooks, Amazon, or visit your local bookseller; and there are any number of older and out-of-print editions available at these same sources!]

- Cousin Phillis and Other Stories. Intro by Heather Glen. Oxford, 2010.

- Cranford. Intro by Patricia Ingham. Penguin 2009; intro by Charlotte Mitchell. Oxford, 2009; Intro by Elizabeth Langland. Broadview, 2010.

- Gothic Tales. Intro by Laura Kranzler. Penguin 2001.

- Life of Charlotte Bronte. Intro by Elizabeth Jay. Penguin 1998; Intro by Angus Easson. Oxford, 2009.

- Mary Barton. Intro by MacDonald Daly. Penguin, 1997; Intro by Shirley Foster. Oxford, 2009; Intro by Jennifer Foster. Broadview, 2000.

- North and South. Intro by Patricia Ingham. Penguin, 1996; Intro by Sally Shuttleworth. Oxford, 2008.

- Ruth. Intro by Angus Easson. Penguin, 1998; Intro by Alan Shelston. Oxford, 2009.

- Sylvia’s lovers. Intro by Shirley Foster. Penguin, 1997; Intro by Andrew Sanders. Oxford, 2008.

- Wives and Daughters. Intro by Pam Morris. Penguin, 1997

What’s Gaskell Worth Now?

Austen’s works show up at auction fairly regularly, but what about Gaskell – how does she compare to the high prices that Austen’s first editions command? There is an upcoming Sotheby’s auction set for October 28 in London: The Library of an English Bibliophile, Part I – all of Austen’s first editions are in the sale with high-end estimates; there are three Gaskell titles in the sale, so this gives a good idea of value:

- Mary Barton. London: Chapman and Hall, 1848. First edition. est. 4,000 – 6,000 GBP

- Ruth. London: Chapman and hall, 1853. First edition. est. 2,000-3,000 GBP

- North and South. London: Chapman and hall, 1855. First edition. est. 2,000-3,000 GBP.

Letters / Diaries:

- Chapple, J.A.V. and Arthur Pollard, eds. The Letters of Mrs. Gaskell. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1966.

- Chapple, J. A.V.; assisted by by J. G. Sharpes. Elizabeth Gaskell: A Portrait in Letters. Manchester: 1980.

- Chapple, John and Alan Shelston, eds. Further Letters of Mrs. Gaskell. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001.

- Chapple J. A. V. and Anita Wilson, eds. Private Voices: the Diaries of Elizabeth Gaskell and Sophia Holland. Keele: Keele UP, 1996.

- Whitehill, Jane, ed. The Letters of Mrs. Gaskell and Charles Eliot Norton, 1855-1865. London: Oxford UP: 1932.

Bibliographies:

- Selig, R. L. Elizabeth Gaskell; A Reference Guide. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1977.

- Jeffery Welch, Elizabeth Gaskell: An Annotated Bibliography, 1929-75. New York: Garland, 1977.

- Weyant, Nancy S. Elizabeth Gaskell: An Annotated Bibliography, 1976-1991. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1994.

- ______________. Elizabeth Gaskell: An Annotated Guide to English Language Sources, 1992-2001. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 2004.

See also Weyant’s online Supplement, 2002-2010 [updated semi-annually]

- See the Gaskell Web page for an online bibliography

Biographies:

- Chapple, John. Elizabeth Gaskell: A Portrait in Letters. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1980.

- ___________. Elizabeth Gaskell: The Early Years. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1997.

- Easson, Angus. Elizabeth Gaskell. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979.

- Ffrench, Yvonne. Mrs. Gaskell. London: Home & Van Thal, 1949.

- Foster, Shirley. Elizabeth Gaskell: A Literary Life. Houndsmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Gerin, Winifred. Elizabeth Gaskell: A Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976.

- Handley, Graham. An Elizabeth Gaskell Chronology. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Hopkins, Annette Brown. Elizabeth Gaskell: Her Life and Work. London: Lehmann, 1952.

- Pollard, Arthur. Mrs. Gaskell: Novelist and Biographer. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1966.

- Uglow, Jenny. Elizabeth Gaskell: A Habit of Stories. London: Faber and Faber, 1993.

- Unsworth, Anna. Elizabeth Gaskell: An Independent Woman. London: Minerva, 1996.

Studies:

- Barry, James Donald. “Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell,” in Victorian Fiction: A Second Guide to Research, edited by George H. Ford. New York: MLA, 1978.

- Beer, P. Reader, I Married Him. . . . London: Macmillan, 1974.

- Cecil, David. Victorian Novelists: Essays in Revaluation. Chicago, 1962.

- Craik, W. A. Elizabeth Gaskell and the English Provincial Novel. London: Methuen, 1975.

- Easson, Angus, ed. Elizabeth Gaskell: The Critical Heritage. London, 1992.

- Ganz, Margaret. Elizabeth Gaskell: The Artist in Conflict. New York: Twayne, 1969.

- Lane, Margaret. Purely for Pleasure. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1966. See chapters on “Mrs. Gaskell’s Task” and “Mrs. Gaskell: Wives and Daughters’.

- Lansbury, Coral. Elizabeth Gaskell: The Novel of Social Crisis. London: Paul Elek, 1975.

- Lucas, John. “Mrs. Gaskell and Brotherhood,” in Tradition and Tolerance in Nineteenth Century Fiction, by D. Howard, J. Lucas, and J. Goode. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966.

- Matus, Jill L. The Cambridge Companion to Elizabeth Gaskell. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007.

- Morris, Pam. “Introduction to Wives and Daughters”. New York: Penguin, 2001.

- Ritchie, Anne Thackeray. “Preface to Cranford”. New Edition. London: Macmillan, 1907.

- Rubenius, Aina. The Woman Question in Mrs. Gaskell’s Life and Work. Uppsala: Lundequist ; Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1950; reprinted by Russell and Russell in 1973.

- Sharps, John Geoffrey Sharps. Mrs. Gaskell’s Observation and Invention: A Study of the Non-Biographic Works. London: Linden, 1970.

- Spencer, Jane. Elizabeth Gaskell. London: Macmillan, 1993.

- Stebbins, Lucy Poate. A Victorian Album: Some Lady Novelists of the Period. New York: Columbia UP, 1946.

- Wright, Edgar. Mrs. Gaskell: The Basis for Reassessment. London: Oxford UP, 1965.

Papers:

Links:

- The Elizabeth Gaskell Collection at Princeton: a catalogue of the collection

- A Bibliographical Guide to the Gaskell Collection at the Moss Side library [Manchester] – full text at Internet Archive

- The Elizabeth Gaskell Information Page which includes many links to e-texts, bibliography, biography, societies, journals, etc

- Elizabeth Gaskell at The Victorian Web

- Edgar Wright Gaskell Page – The Dictionary of Literary Biography, includes a short biography, images, bibliography

- The Gaskell Society

- The Elizabeth Gaskell Blog – a new blog devoted to Gaskell, launched Sept. 29, 2010!

- The Elizabeth Gaskell House

- Elizabeth Gaskell page at Virtual Knutsford

- A Gaskell Chronology: at the Gaskell Web and at the Victorian Web

- Penguin Classics on the Air: Four Podcasts on Who is your favorite Novelist, Jane Austen or Elizabeth Gaskell?

- Editor-in-Chief Stephen Morrison leads a discussion with two experts on Austen and Gaskell: Sue Birtwistle, the producer of the much-loved adaptation of Pride & Prejudice starring Colin Firth and the co-creator and producer of Cranford and producer of Return to Cranford starring Judi Dench based on Gaskell’s novel Cranford. Stephen also speaks with Tanya Agathocleous, an Assistant Professor of English literature at Hunter College, specializing in 19th and 20th Century British Literature & Culture.

- The Gaskell Bicentenary Celebration at Cheshire’s Peak District

Ebooks:

- Mary Barton

- North & South

- Cranford

- Wives & Daughters

- Life of Charlotte Bronte

- An Accursed Race

- Cousin Phillis

- Cranford

- Curious, if True Strange Tales

- A Dark Night’s Work

- Doom of the Griffiths

- The Grey Woman and other Tales

- Half a Life-Time Ago

- The Half-Brothers

- A House to Let

- Life of Charlotte Brontë — Volume 1

- Life of Charlotte Bronte — Volume 2

- Lizzie Leigh

- Mary Barton

- The Moorland Cottage

- My Lady Ludlow

- North and South

- The Poor Clare

- Round the Sofa

- Ruth

- Sylvia’s Lovers — Complete

- Sylvia’s Lovers — Volume 1

- Sylvia’s Lovers — Volume 2

- Sylvia’s Lovers — Volume 3

- Victorian Short Stories: Stories of Successful Marriages (as Contributor)

- Wives and Daughters

- Cranford

- Dark Night’s Work, A

- Doom of the Griffiths, The

- Half a Life-Time Ago

- Lizzie Leigh

- Mary Barton

- My Lady Ludlow

- Poor Clare, The

- Wives And Daughters

- An Accursed Race

- Half-Brothers, The

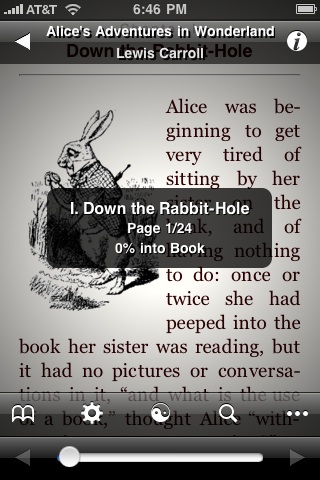

Ebook editions at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Borders:

- The [Kindle] Works of Elizabeth Gaskell – at Amazon, for $3.99 you can download most of her works to your Kindle; but if you search further, there are several free downloads of the individual novels, and other various collections; review the contents before selecting.

- Barnes & Noble: same as Amazon, some collections for $3.99, many free options.

- Borders: has various similar options

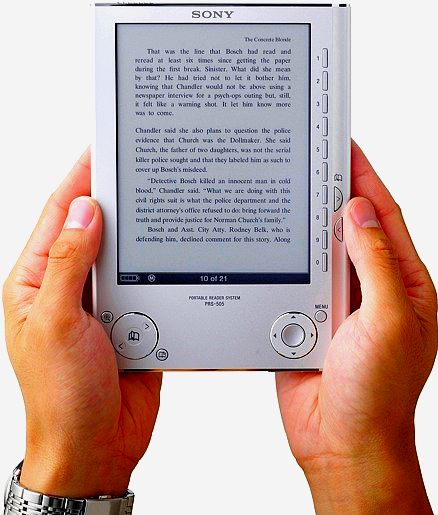

iPhone Apps:

Whatever you use for books on your iPhone, there are plenty of free Gaskells available. I use Stanza, which is a free app [there are many others – visit your iTunes store and search “books” under Apps and see what I mean!], and from there you can choose the following: Feedbooks has several; Project Gutenberg has the same as online noted above; but Munsey’s takes first prize for having the most – seems to have all the novels and stories as best I can make out – so if you are stranded at an airport or in stopped traffic, what better way to pass the time than a Gaskell short story?!

Audiobooks:

- Cousin Phillis (unabridged)

- Cranford (unabridged)

- North and South (abridged)

- North and South (unabridged)

- Wives and Daughters (unabridged)

- Wives and Daughters (abridged)

- Silksounds: has only My Lady Ludlow, read by Susannah York [very good!]

- CSA Word: Best of Women’s Short Stories, vol. 1& 2. Read by Harriet Walter [a.k.a. Fanny Dashwood] Includes Gaskell’s “Right at Last” and “The Half Brothers”; CSA Word also has an abridged version of Mary Barton [read by Maggie Ollerenshaw] and North and South [read by Jenny Agutter].

- LibriVox:

- North & South

- Other Gaskell works in various states of completion

Movies: [see the various blog posts listed below for movie reviews]

- Wives & Daughters (1999)

- North & South (2004) – with Richard Armitage and Daniela Denby-Ashe ~ sigh!

- North & South (1975) – with Patrick Stewart and Rosalind Shanks

- Cranford (1972)

- Cranford / Return to Cranford (2007, 2009)

- Cousin Phillis (1982) –

- The Gaskell Collection – DVDs – includes 7 discs: W&D, N&S, CRANFORD and all special features.

*******************************

Well, there’s a fine list for winter reading, listening and viewing! And somewhere in the middle of all that, treat yourself to a re-watch of Armitage in North and South! [and then of course READ it again … here is a link to an older blog post about the book and movie]

************************

This is a rather quick list of goodies – if any of you know of a particular edition of a book, or an ebook, or an audio edition you particularly like, or a movie that I do not mention, please let me know so I can add it to the list – thank you!

Follow this link to to the next blog on the Elizabeth Gaskell Bicentenary Blog Tour by Tony Grant at London Calling: Plymouth Grove – A Visit to Elizabeth Gaskell’s home in Manchester

***********************

The Gaskell Blog Tour: Here is the complete tour through the 15 blog posts celebrating Gaskell’s Birthday today: and remember that one lucky commenter will win a copy of an unabridged edition of North and South by Naxos AudioBooks read by Clare Willie. That’s 18 hours of Margaret Hale and John Thornton sparring and sparking in Gaskell’s most acclaimed work. Here is a list of participants. You can visit them in any order and all comments during the contest will count toward your chance to win. Good luck and Happy Birthday Mrs. Gaskell!

Biography

Novels/Biography

Novellas

Resources

“Sometimes one likes foolish people for their folly, better than wise people for their wisdom.” Elizabeth Gaskell, Wives and Daughters

[Posted by Deb]

Tonight at midnight [10-7-10, Pacific Time] is the deadline for commenting on any of the blog posts on the Elizabeth Gaskell Blog Tour and to enter to win the Naxos audiobook of North and South. You can comment on my Gaskell post: Your Gaskell Library, or any of the posts below. Good luck! – Lovely prize! Laurel Ann at Austenprose will be announcing the winner tomorrow, October 8th.

Tonight at midnight [10-7-10, Pacific Time] is the deadline for commenting on any of the blog posts on the Elizabeth Gaskell Blog Tour and to enter to win the Naxos audiobook of North and South. You can comment on my Gaskell post: Your Gaskell Library, or any of the posts below. Good luck! – Lovely prize! Laurel Ann at Austenprose will be announcing the winner tomorrow, October 8th.

Dancing with Mr Darcy: Stories inspired by Jane Austen and Chawton House Library

Dancing with Mr Darcy: Stories inspired by Jane Austen and Chawton House Library