I begin with my own prejudice – Persuasion has long been my favorite Austen novel. One cannot dispute the joy of reading Pride and Prejudice; or the laughter at the pure innocence and brilliance of Northanger Abbey; we can sympathize with the moral steadfastness of Fanny in Mansfield Park, savor the (im)perfections of Emma (both the book and heroine!), and revel in that dawning realization that Sense and Sensibility is so much better than at first thought. But it is Persuasion that holds my abiding affection – a novel of second chances, a novel that seems closest in some inexplicable way to Jane Austen herself, a romance where she actually plays out the agony of lost and found love, and so unlike her, a profession of love that she actually doesn’t back off from and leave the reader to their own imaginings!

I begin with my own prejudice – Persuasion has long been my favorite Austen novel. One cannot dispute the joy of reading Pride and Prejudice; or the laughter at the pure innocence and brilliance of Northanger Abbey; we can sympathize with the moral steadfastness of Fanny in Mansfield Park, savor the (im)perfections of Emma (both the book and heroine!), and revel in that dawning realization that Sense and Sensibility is so much better than at first thought. But it is Persuasion that holds my abiding affection – a novel of second chances, a novel that seems closest in some inexplicable way to Jane Austen herself, a romance where she actually plays out the agony of lost and found love, and so unlike her, a profession of love that she actually doesn’t back off from and leave the reader to their own imaginings!

But here today, I am only going to talk of how it all came to be. I’ve already written about the interesting publishing journey of Northanger Abbey here – and Persuasion, because it was published along with NA in a 4-volume set after Austen’s death, is bound up (literally) in that publishing story, Northanger Abbey, her earliest completed work, and Persuasion, her last – and why Sarah Emsley on her blog has called her celebration of these two works as “Youth and Experience.”

But other than being bound together in late December 1817, the journey of Persuasion’s composition and publication is quite different, as we shall see.

How it came to be:

Cassandra’s “Memorandum” (see Minor Works, facing p 242), where she wrote the dates of the composition of each of the novels, tells us that Austen began Persuasion on August 8, 1815 and wrote “Finis” at the end of the manuscript on July 18, 1816.

We know from her nephew James Edward Austen Leigh’s 1871 Memoir that Austen was dissatisfied with the ending, she thought it “tame and flat:” she rewrote chapter 10 (i.e.chapter 10 of volume 2), added chapter 11, and retained chapter 12 (which had been the final chapter 11). This final version was finished on August 6, 1816.

These handwritten original two chapters are the only extant manuscripts of Austen’s novels. These were first printed in the 1871 second edition of the Memoir, and this was the accepted text until the actual MS became available on December 12, 1925 and was edited and published by R. W. by Chapman under the title Two Chapters of Persuasion (Oxford, 1926). The manuscripts are now housed in the British Library, and you can see the transcribed text beside the facsimile online at Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts: http://www.janeausten.ac.uk/manuscripts/blpers/1.html

As these cancelled chapters are included in most modern scholarly editions of the novel, I shall assume you have read them and will only summarize here: Austen has Anne meeting Admiral Croft on her way home from Mrs. Smith’s (and where she has just learned of the true character of William Elliot) – she is invited to visit Mrs. Croft, and assured of her being alone, she accepts, and to her consternation finds Capt. Wentworth at home. Admiral Croft has asked Wentworth to find out from Anne if the rumors are true she is to marry her cousin and thus might want to move into Kellynch Hall. Wentworth is quite beside himself but does as asked, “irresolute & embarrassed;” with Anne’s adamant assurance that nothing is farther from the truth, they have

a silent, but very powerful Dialogue;- on his side, Supplication, on hers acceptance. – Still, a little nearer- and a hand taken and pressed – and “Anne, my own dear Anne!” – bursting forth in the fullness of exquisite feeling – and all Suspense & Indecision were over. – They were reunited. They were restored to all that had been lost.

Etc. etc… explaining all their past feelings and misunderstandings and a final chapter of future plans, they are left “with little to distress them beyond the want of Graciousness and Warmth” once their news was spread to family and friends, ex-potential lovers and a scheming Mrs. Clay.

A discussion of why Austen made these changes is beyond the topic here at hand – but we can agree with Austen’s own assessment that it was too “tame and flat:” she needed to pull all the characters together – the Musgroves, Benwick and Harville, the Crofts, and the obtuse Elliots; she needed to increase the tension and suspense between Anne and Wentworth; she wanted to give Anne a strong voice in her conversation with Harville, all overheard by Wentworth; and of course she needed the Letter – what would Persuasion be without “You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope…”? !

I will note that in the movie version (Amanda Root – Ciaran Hinds, Sony/BBC 1995) – and I think the most perfect of all the Austen adaptations – a part of this scene with Wentworth and Anne is added to the plot, Wentworth confronting Anne in the Assembly Room at Admiral Croft’s request, Wentworth sure of her impending engagement to Elliot, and Anne, unable to answer in her confusion and hurt, runs off. This leads to the scene as written at the Inn – Wentworth listening and composing, the remainder of the film following the book. – This is all worthy of further conversation!

But one of Austen’s classic lines is not in the final novel – the first draft is a bit more comic in nature, and perhaps she thought it not fitting the more somber nature of this work:

It was necessary to sit up half the Night & lie awake the remainder to comprehend with composure her present state, & pay for the overplus of Bliss, by Headake & Fatigue.

************************

That Austen made these changes is a gift to later generations, as it is in this manuscript that we are given a rare glimpse into how meticulous she was in her writing and editing methods, crossing out and rewriting, looking for the exactly correct word or phrase.

We know little about Persuasion from Austen herself: it is only mentioned in her Letters twice, though not by name:

On March 13, 1817 she wrote to her niece Fanny Knight:

I will answer your kind questions more than you expect. – Miss Catherine (meaning Northanger Abbey) is put upon the Shelve for the present, and I do not know if she will ever come out; – but I have a something ready for Publication, which may perhaps appear about a twelvemonth hence. It is short, about the length of Catherine – This is for yourself alone… [Letter 153, Le Faye]

And again on March 23, 1817:

Do not be surprised at finding Uncle Henry acquainted with my having another ready for publication. I could not say No when he asked me, but he knows nothing more of it. – You will not like it, so you need not be impatient. You may perhaps like the Heroine, as she is almost too good for me. [Letter 155, Le Faye]

The working title for Persuasion was “The Elliots” – as there is no evidence that Austen chose the titles for either Northanger Abbey or Persuasion, it is generally accepted that her brother Henry titled both; and we might agree with him: interesting to note that “persuasion” in one form or another in mentioned in the novel at least 29 times – you can go to this hyper-concordance to Jane Austen to search for all the occurrences: http://victorian-studies.net/concordance/austen/

Henry must have delivered the manuscripts of both Northanger Abbey and Persuasion to John Murray very soon after Austen’s death on July 17, 1817. Murray wrote to Byron, whose works Murray also published, in early September 1817 telling him that of the new books he was about to publish included “two new novels left by Jane Austen, the ingenious author of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ who, I am sorry to say, died six weeks ago.” (Gilson, xxx.)

So, one question to ask is if Austen “finished” Persuasion in August 1816, why write seven months later that it “may perhaps appear about a twelvemonth hence” ??? What kept her from sending it along to Murray upon completion if she was happy with it in March of 2017?

Austen’s life when she was writing Persuasion:

If we look at the writing of Persuasion on a blank canvas – she started it in August 1815, finished August 1816 – we do not get a complete sense of Austen the woman, the sister, the friend, the author. I find it most fascinating to look at her life in that year and ask what else was going on while she used her spare quiet moments to write this her last novel:

– She visits London and is staying with Henry in October 1815 and stays until mid-December. She is working on the proof sheets of Emma, Henry negotiating with Murray to publish Emma and a 2nd edition of Mansfield Park – she is also working on the corrections for this 2nd edition.

– Henry falls dangerously ill, and Austen takes on writing letters to Murray herself while nursing Henry; she requests all family members to come as there is growing concern he will not survive.

– It is conjectured that one of Henry’s doctors, Matthew Baillie, learned of his sister being the author of Pride & Prejudice, etc. and passed this word on to the Prince Regent. On the 13th of November, Austen visits Carlton House at the request of the Prince Regent’s Librarian James Stanier Clarke – she is also asked to dedicate her soon-to-be-published Emma to his “Royal Highness” – and though she hated this prospect, it likely sped up the printing process. (One aside: she had to pay for the Prince’s 3 vol. beautifully bound copy of Emma…)

– In late November, the Alton bank fails and bankruptcy looms over Henry and his partners.

– Austen leaves London on her birthday 16 December 1815 once Henry is fully recovered and the initial fear of bankruptcy seems allayed; Emma is published on 23 December 1815 (title page says 1816).

– In early 1816, Henry buys back “Susan / Catherine / Northanger Abbey” from Crosby for the £10 originally paid to Austen in 1803 and she begins to make a few edits, writes her “Advertisement” and by March it is “put upon the Shelve at present.” (Crosby went bankrupt shortly thereafter).

– In February, her brother Charles, commanding the HMS Phoenix, is caught in a storm off the Greek Archipelago and runs aground. He is brought up for a court-martial in April for his responsibility in the action but is completely acquitted.

– There is the ongoing lawsuit that threatens Edward Austen Knight’s properties – and this is not resolved until after Jane’s death (see Ltr. 122, October 17-18, 1815 for one reference to Edward’s “Cause”).

– And sometime in here she writes her very funny “Plan of a Novel” – inspired without question by her correspondence with Clarke which lasted from November 1815 to April 1816. [You can read this as well online here: http://www.janeausten.ac.uk/manuscripts/pmplan/1.html ].

– By mid-March, Henry is declared bankrupt and his life as a banker, and Austen’s chief financial support in her publishing endeavors, is over. This is a dreadful blow to the entire family – he can no longer offer any support to his mother and sisters; Edward has lost a good deal of money and will be responsible for many of the debts; and James is at risk of losing his inheritance in the Leigh-Perrot estate. The bankruptcy is resolved by June – but Henry has had to sell off everything (for a fine accounting of the details of Henry’s home furnishings, see Clery, 268).

– Emma is published in late December and initially does very well, but sales begin to slack off after the March 1818 Quarterly Review essay by Walter Scott. Appearing to offer praise to Austen’s narrative voice and abilities to portray her few families with wit and precision, Clery finds that the negative tone of the review, the emphasis on what Austen leaves out of her works and his failure to mention Mansfield Park at all, greatly influenced Austen’s writing of Persuasion.

She is writing this work during these many crises of health and possible death and financial losses. No wonder she writes of an extravagant family on the brink of ruin and characters with various health issues. Clery makes another point I confess to never thinking of before – could her Sir Walter be some sort of slam at Walter Scott?? (Clery, 272) – You can compare Austen’s Emma sales (1409 copies sold early on) with Scott’s own sales for his Rob Roy, also published in late December 1817 and which sold 10,000 copies in two weeks.

– In the context of the wider world, there was the ever-expanding and more competitive market for publishing novels in Austen’s time. In 1775, the year she was born, 31 new novels were published; in 1811, when Sense & Sensibility appeared, 80 new fiction works appeared; for the year 1818, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion were published along with 61 other novels. Altogether, 2,503 new novels were published in the years between 1775 and 1818. (Raven, 195-6)

So to answer my own question: why did Austen not publish Persuasion after she finished it? Her brother was no longer able to cover the costs of publication and loss if sales should fail; and, the signs of her own declining health were beginning in mid-1816, that summer, “the year without a summer” due to the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia. It is a wonder she was able to write anything at all, much less go on with working on her brilliant Sanditon, put aside on 18 March 1817…

What did the book look like?

– It was published posthumously in December 1817 [though the title page says 1818] with Northanger Abbey

– Title page states: “By the Author of ‘Pride & Prejudice,’ ‘Mansfield Park,’ etc.”; With a “Biographical Notice of the Author,” (dated Dec. 20, 1817, by Henry Austen, thus identifying his sister as the author to the public for the first time)

– Published by John Murray, London; 1818; in four volumes: the two Northanger Abbey volumes printed by C. Roworth; the two Persuasion volumes by T. Davison of Lombard St.

– Included is the “Advertisement by the Authoress to Northanger Abbey” where Austen “apologizes” for the datedness of the story and zings the dastardly publisher for withholding the book for 10 years…

– Advertised first in The Courier 17 December 1817 as to be published on 20 December in 4 volumes, 24s.: “Northanger Abbey, a Romance; and Persuasion, a Novel.” The advertisement in The Morning Chronicle appeared on the 19th (“Tomorrow will be published”) and the 20th of December 1817 (“Books published this day”).

Physical description:

- 12mo or about 7.5″ tall, with text on pages not crowded but about 5-8 words / line and about 21 lines / page in vol. 3; 22 lines / page in vol. 4 – and interesting to note that unlike the Northanger volumes there are no catchwords used in the Persuasion volumes

- blue-grey paper boards, off-white or grey-brown backstrips, white paper labels (there are a number of variants) –

Size of run: @ 1750 copies [various opinions on this; some say 2500 copies] – 1409 copies sold very quickly, the majority to circulating libraries

Cost: 24 shillings for the 4 volumes

Profit: @£515 – like Austen’s other works, Persuasion was published on commission: Austen paid for costs of production and advertising and retained the copyright; the publisher paid a commission on each book sold – the exception was Pride & Prejudice for which she sold the copyright to Thomas Egerton

What is it worth today?

Price Guides (estimates in 2007): Original binding: $75,000 / Rebound copy: $20,000

An online search on Abebooks, March 15, 2018 brings up five copies of the 4-volume 1st edition, none in original boards, and range from $11,000 to $25,000

In 2010, a 1st edition in original boards sold at Sotheby’s for £43,250 ($68,396) with an estimate of 31,628 — 47,442 USD)

Where can you find a copy?

I love this tidbit (from Gilson): Queen Elizabeth has in her personal library at Windsor Castle Sir Walter Scott’s copy of the 1st edition.

Gilson notes where copies of the 1st edition can be found (other than the Queen’s and therefore more accessible to all, and certainly at least one of these will be close to you!), at all the usual suspects in various bindings: Goucher, the Bodleian, Boston Athenaeum, Boston Public Library, British Library, Cambridge, Jane Austen’s House Museum, Columbia, Library of Congress, U of Edinburgh, U of Glasgow, Harvard, London Library, National Library of Scotland, the Morgan Library, New York Public Library, U of Toronto, Yale, Williams, etc. See the rest of Gilson’s list on pg 88-91.

When was the First American edition published?

Persuasion was published in America by Carey & Lea of Philadelphia in two volumes in 1832, separate from Northanger Abbey which was published in two volumes in 1833. The title page states “by Miss Austen, Author of ‘Pride and Prejudice,’ ‘Emma,’ ‘Mansfield-Park,’ etc.” Bound in drab paper boards with purple cloth spines with white spine labels, the spine reads: “Persuasion, by Miss Austen / Author of Pride and Prejudice.” 1250 copies were printed, and advertised on November 8, 1832 as “Persuasion, a novel, by Miss Austin [sic]” as being published that day. (And people have been getting it wrong ever since!) Gilson points out the various modifications to language typical of all the American editions of Austen’s novels, mostly those having to do with the Deity, for instance “Lord bless me!” is changed to just “Bless me!”

Estimated value: Original binding: $10,000 / Rebound copy: $5,000

You can find two copies available online at Abebooks: $10,000 and $15,000 – both in original boards.

Parlez-vous francais? Persuasion in French:

La Famille Elliot ou “L’Ancienne Inclination” [ “the old or former inclination”] translated by Isabelle de Montolieu, was published in Paris in 1821 by Arthus Bertrand. This is the first published novel to have Austen’s full name on the title page and to include illustrations: an engraved frontispiece in each volume (Delvaux after Charles Abraham Chasselat). In volume I we find Capt. Wentworth removing two-year old Walter Musgrove from Anne’s back; and in volume II, here we see Wentworth placing his heart-wrenching letter before Anne.

You can read the full text (in French) here: https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/La_Famille_Elliot

The French texts of Austen’s novels, what Southam calls “travesties not translations,” (26) were modified to fit the tastes of the sentimental French reading public. In Persuasion, Montolieu changes the ending by restoring Anne to Kellynch rather than leaving the future of Capt. Wentworth and Anne dependent upon a lasting peace. (See Cossy, 176) One notable change (and why we might ask!), is that Anne’s name is changed to Alice!

The First Illustrated Edition in England:

Richard Bentley purchased the copyrights of Austen’s novels from Henry and Cassandra in 1832 (and the copyright of P&P from Thomas Egerton) and in 1832-33 he published all the novels in his Standard Novels series. These were the first English editions to carry illustrations – steel-engraved frontispieces and title page vignettes by William Greatbatch after George Pickering. Northanger Abbey and Persuasion were published in 1833 in a single volume together with the frontispiece from Northanger Abbey (Henry coming up the stairs surprising Catherine) and the title vignette from Persuasion showing a seated Anne overhearing Capt. Wentworth talking to Louisa Musgrove. All very Victorian!

The Timeframe of Persuasion:

Though Austen is often been criticized for creating an insular world with little commentary on outside real-life events, such thinking is belied with a close study of Persuasion, where one finds a very specific chronology easily linked to the historical reality of the time depicted.

– The first paragraph of Persuasion sets us into this timeframe with quoting the “Elliot of Kellynch Hall” entry from the Baronetage, the only work Sir Walter seems capable of reading, and where we learn the birth and death dates of everyone in the family – we learn that Anne was born on August 9, 1787 and a still-born son in 1789, and that Anne’s mother died in 1801.

– In chapter 4, we are given the very specific time that Capt.Wentworth stayed with his brother at Monkford for six months over the summer of 1806. This is the backstory of Persuasion, the current story often called a sequel to this original tale of love, all now told in four pages…

– The exact time of the action is set a few pages on in chapter 1: “…at the present time, (the summer of 1814)…,” and in chapter 3, a direct reference to the peace: “This peace will be turning all our rich Naval Officers ashore.” The Peace of Paris was signed on May 30, 1814, Napoleon abdicating and off to Elba. There were celebrations in London that Austen refers to in her letters:

Allied Sovereigns Attending a Review in Hyde Park June 1814

Duke of Wellington, King of Prussia, Prince Regent (later George IV), and Emperor of Russia

Austen writes Cassandra who is in London with Henry:

Take care of yourself, & do not be trampled to death in running after the Emperor. The report in Alton yesterday was that they certainly would certainly travel this road either to, or from Portsmouth. – I long to know what this Bow of the Prince’s will produce.- [Ltr 101, 14 June 1814]

– The Elliots travel to Bath sometime in mid-September, Anne goes to Uppercross Cottage, and on Michaelmas, September 29, the Crofts take over Kellynch.

– Captain Wentworth arrives in October; they all visit Lyme Regis in November (this is 17 miles from Uppercross). In January Lady Russell takes Anne to Bath (Mary’s letter to Anne in Bath is dated February 1815, this carried by the Crofts when they come to Bath for the Admiral’s health). Captain Wentworth follows not far behind, all is beautifully settled with Anne, and the novel ends in March of 1815.

– In the real world, Napoleon escapes Elba and returns to Paris by March 20, 1815 – this is after Persuasion  ends, before Waterloo in June 1815, and why Austen ends the novel with the unknown state of the peace leaving Anne and her Captain in limbo. In truth, the Navy was not mobilized in the spring of 1815, and so we might rest comfortably in that reality of Wentworth not being returned to a Ship and War – and contemporary readers in late 1817 would have known that… but Austen chooses to emphasize that any such “peace” is likely not long-lasting, as we know all too well even today…

ends, before Waterloo in June 1815, and why Austen ends the novel with the unknown state of the peace leaving Anne and her Captain in limbo. In truth, the Navy was not mobilized in the spring of 1815, and so we might rest comfortably in that reality of Wentworth not being returned to a Ship and War – and contemporary readers in late 1817 would have known that… but Austen chooses to emphasize that any such “peace” is likely not long-lasting, as we know all too well even today…

Austen’s personal knowledge of Bath, Lyme Regis and the Navy is paramount in Persuasion, but it is interesting to note regarding the Navy and pointed out by Brian Southam in his Jane Austen and the Navy, that not a single critic or commentator addresses her sailors and officers as a social class until Richard Simpson’s review of James Edward Austen Leigh’s 1870 Memoir in the North British Review of April 1870.

And one date in this novel that has always made me wonder: why does Austen have Charles and Mary Musgrove marry in 1810 on her very own birthday of December 16?? Any thoughts?? There is a long gap in the letters here: from July 26, 1809 to April 20, 1811, so we have no idea what was going on in Austen’s own life on that date in 1810 – we can only wonder that it was not some sort of code to her family of readers…

(For a complete calendar to the events in Persuasion see Ellen Moody’s post here: http://www.jimandellen.org/austen/persuasion.calendar.html

What did the earliest reviewers have to say?

The early reviews of the two-novel publication all make reference to the sadness of her death and, now finally identified to the public in Henry’s “Biographical Notice,” a general lament that no other works will come from her pen. I will give a quick summary here of the four earliest reviews as this is really a topic for another blog post entirely:

British Critic, December 1817, an unsigned review: After commenting on the talents of Jane Austen, where “some of the best qualities of the best sort of novels display a degree of excellence that has not been often surpassed,” the writer goes on to summarize and highly praise Northanger Abbey. Persuasion is given short shrift with a concluding paragraph I quote in its entirety:

British Critic, December 1817, an unsigned review: After commenting on the talents of Jane Austen, where “some of the best qualities of the best sort of novels display a degree of excellence that has not been often surpassed,” the writer goes on to summarize and highly praise Northanger Abbey. Persuasion is given short shrift with a concluding paragraph I quote in its entirety:

With respect to the second of the novels, it will be necessary to say but little. It is in every respect a much less fortunate performance than that which we have just been considering. It is manifestly the work of the same mind, and contains parts of very great merit; among them, however, we certainly should not number its moral, which seems to be, that young people should always marry according to their own inclinations and upon their own judgment; for that in consequence of listening to grave counsels, they defer their marriage, til they have wherewith to live upon, they will be laying the foundation for years of misery, such as only the heroes and heroines of novels can reasonably hope ever to see the end of. (quoted in Southam, Critical Heritage, v.1, 84)

- Edinburgh Magazine & Literary Miscellany, May 1818, an unsigned notice (Mary Waldron corrects the

common error that this was in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine). The writer calls Austen an “amiable and agreeable authoress,” that she…

common error that this was in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine). The writer calls Austen an “amiable and agreeable authoress,” that she…

will be one of the most popular of English novelists” and “within a certain limited range, has attained the highest perfection of the art of novel writing…We think we are reading the history of people whom we have seen thousands of times – with much observation, much fine sense, much delicate humour, many pathetic touches, and throughout all her works, a most charitable view of human nature, and a tone of gentleness and purity.”

All ends with my favorite line of any critic: “…novels as they are, and filled with accounts of balls and plays, and such adbominations…” !

- Gentleman’s Magazine, July 1818, notice / obituary. Southam quotes these words on NA and P:

The two Novels now published have no connection with each other. The characters in both are principally taken from the middle ranks of lie, and are well supported. Northanger Abbey, however is decidedly preferable to the second Novel, not only in the incidents, but even in its moral tendency. (16)

- Quarterly Review, January 1821, unsigned review but attributed to Richard Whately, the Archbishop of Dublin.

Whately reviews all the novels, Austin [sic] for him a serious writer whose “moral lessons, though clearly and impressively conveyed, are not offensively put forward, but spring incidentally from the circumstances of the story…that unpretending kind of instruction which is furnished by real life…her fables nearly faultless.” After a humorous take on John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey as “the Bang-up Oxonian,” Whately concludes with an analysis of romantic love as portrayed in Persuasion, and calling it her most superior work, “one of the most elegant fictions of common life we ever remember to have met with.”

As Southam points out, none of these early critics and readers “were ready to accept her disconcerting account of the ways and values of their own society” and therefore failed to “identify the force and point of her satire.” (Southam, Critical Heritage, 18) Such was left to future generations!

And this great bulk of modern criticism and commentary continues to enlighten us – and does so right here on Sarah Emsley’s blog with an array of writers who will offer interesting and insightful ways to approach Persuasion – the journey starts this week – Check back and join the conversation!

Sources:

- Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. 4th ed. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. Oxford UP, 2011.

- _____. The Novels of Jane Austen: the Text Based on Collation of the Early Editions. 3rd ed. Ed. R. W. Chapman. Vol. V, Northanger Abbey & Persuasion, Oxford, 1933. [with revisions] Introductory material

- _____. Persuasion. Ed. James Kinsley. Introd. Deidre Shauna Lynch. Oxford UP, 2008.

- Clery, E. J. Jane Austen: The Banker’s Sister. Biteback, 2017.

- Cossy, Valerie, and Diego Saglia. “Translations.” In Todd, 169-81.

- Gilson, David. A Bibliography of Jane Austen. Oak Knoll, 1997.

- Johnson, Claudia L., and Clara Tuite, ed. A Companion to Jane Austen. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen: The World of her Novels. Frances Lincoln, 2002.

- Raven, James. “Book Production.” In Todd. 194-203.

- Southam, Brian. Jane Austen and the Navy. 2nd ed. National Maritime Museum, 2005.

- _____, ed. Jane Austen: The Critical Heritage, Vol. I, 1811-1870. Routledge, 1979.

- Sutherland, Kathryn. “Chronology of Composition and Publication.” In Todd, 12-22. (See also Sutherland’s Jane Austen’s Textual Lives. Oxford, 2005)

- Todd, Janet, ed. Jane Austen in Context. Cambridge, 2007. See essays cited separately.

- Waldron, Mary. “Critical Responses, Early.” In Todd, 83-91.

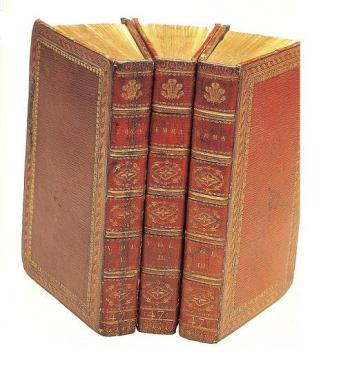

A pristine 1st of Emma for sale last year for £100,000

A pristine 1st of Emma for sale last year for £100,000